3 March 2017 marks 170 years since the birth of Scottish inventor Alexander Graham Bell. This post explores his life and controversial career, and outlines the crucial importance to Bell of a lifelong study of speech, sound and the mechanics of the human voice and hearing in informing his experimental work, which led to the development of his famous ‘speaking telegraph’

Early life in Edinburgh

Alexander Bell was born in Edinburgh on 3 March 1847. At the age of eleven he chose to add the middle name of Graham, which stuck for the rest of his life.

Sound and speech were part of Bell’s life from a young age. Both his father and grandfather were well-known teachers of elocution and speech training; his father in Edinburgh, his grandfather in London.

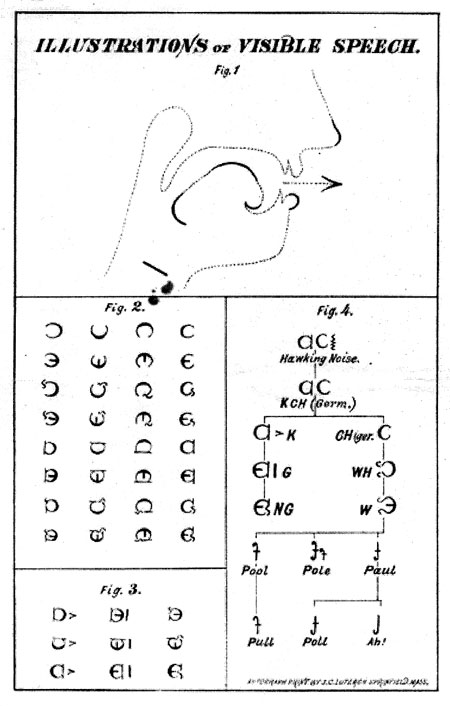

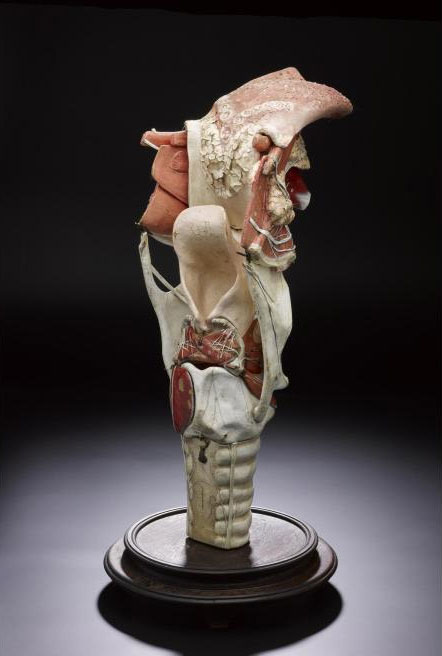

His father’s work focused on developing a system of ‘visible speech’, which allowed speech sounds to be written down. He aimed to use this visualisation as a means of teaching deaf people to speak, without them ever having heard words spoken. Encouraged by his father, young Bell attempted to make working models of ear and vocal chords, aiming to create a mechanical speech device. He attended classes in anatomy and physiology in London for a couple of years, building his understanding of how speech and hearing worked.

Following the death of both of Bell’s brothers from tuberculosis, in 1870 the family emigrated to a healthier life in Canada. Building on his father’s earlier work on the human voice, Bell started teaching deaf students in Boston, moving to the United States in 1871. Two years later, he was appointed Professor of Vocal Physiology and Elocution at Boston University.

These early experiments in speech creation, along with his knowledge of anatomy, informed his own experiments on transmitting speech, which he began in earnest from 1873.

Patent for the telephone

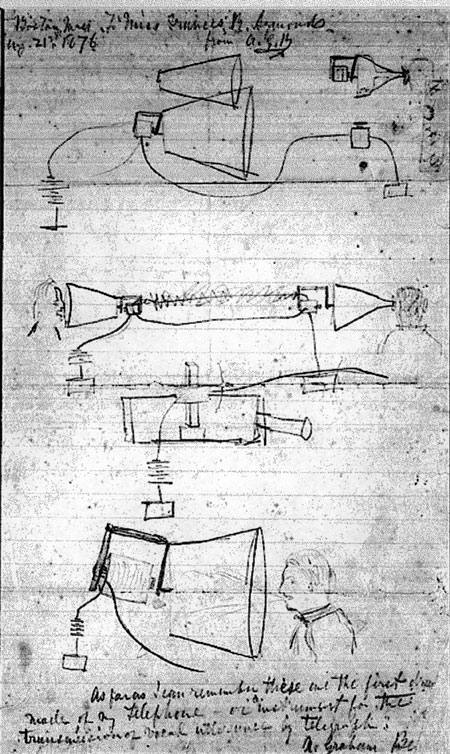

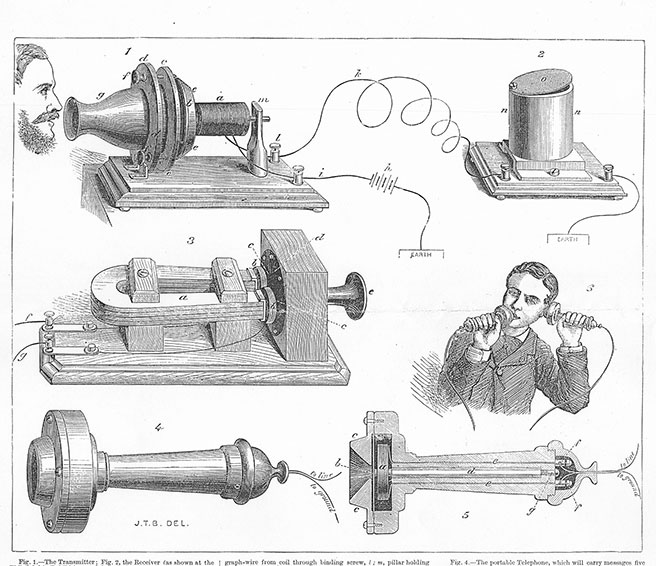

Bell did not think he was inventing a ‘telephone’ during his early experiments. He was working on the holy grail of the day: sending multiple telegraph messages over the same wire. He aimed to make electro-mechanical devices capable of transmitting and receiving different tones for each message.

He was supported financially in this work by the father of one of his students, Gardiner Hubbard, a wealthy lawyer and politician, whose deaf daughter, Mabel, had been taught to lip-read and speak by Bell. Bell fell in love with Mabel. Her father, being aware of Bell’s experiments with possible ‘speaking telegraph’ devices, refused his permission for the couple to marry until Bell had successfully developed his new invention. To speed matters along, he also funded an assistant, Thomas Watson.

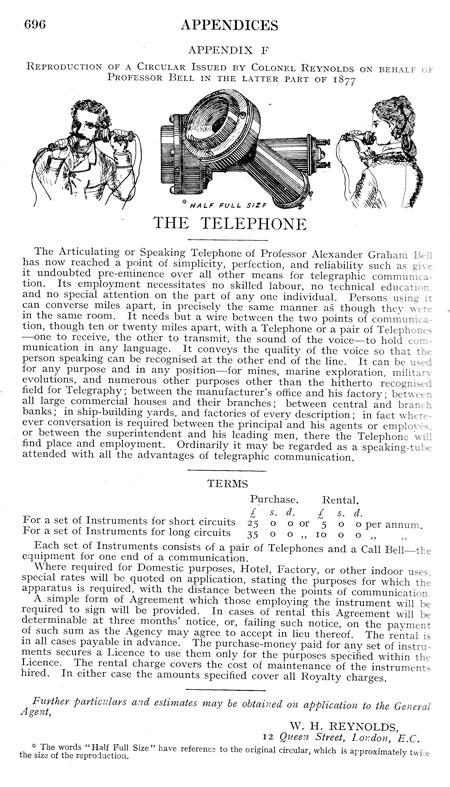

Sensing the danger of rival developments for this valuable invention, Bell’s future father-in-law filed an application for ‘Improvements in Telegraphy’ on 14 February 1876. On that very same day a few hours later – or was it actually a few hours earlier? – inventor Elisha Gray filed his own idea for a telephone at the same office. Bell was granted the patent on 7 March 1876. On 9 July 1877, Bell, Hubbard, Watson (and other funders) established the Bell Telephone Company to market the new device. Bell and Mabel married two days later.

Controversy remains as to whether Bell or his father-in-law might have had access to the details of Gray’s patent through an office clerk in Hubbard’s pay. The clerk seemed to admit as much in a later court case, but Bell’s patent was upheld, as it was in the many cases which followed.

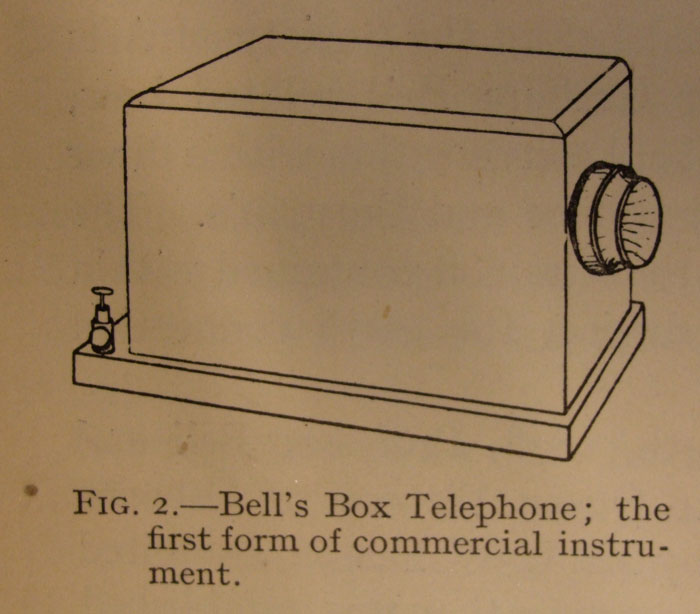

On 11 August 1877, Bell and Mabel arrived in Britain from the USA on honeymoon. In Bell’s luggage was his new communication device, the telephone. Bell travelled the country promoting his invention, even demonstrating the device to Queen Victoria, who was so amused she asked to keep the temporary installation in place. The first telephones went on sale later that year.

Other telephone pioneers

Sometimes described as the most valuable patent ever filed, for years following the award, Bell had to defend his patent in expensive and protracted litigation battles brought by a whole range of inventors. In 2002, the US Congress formally recognised Italian Antonio Meucci as the true inventor of the telephone, based on prototypes he demonstrated in 1860. Bell and the Italian had shared a workshop in the 1870s. Meucci was pursuing his claim in the Supreme Court when he died in 1889. France and Germany cite their own contenders for the title.

In many respects, Bell’s telephone was flawed, his receiver and transmitter designs being considerably improved by others within a couple of years. Among those were Thomas Edison and Professor David Hughes, who both produced improvements to Bell’s early instrument, transforming the telephone into a truly successful communication device.

Thomas Edison patented a more efficient transmitter, making longer distance calls a realistic prospect. After several court cases accusing each other of patent infringements, Bell and Edison joined forces forming the United Telephone Company in Britain in 1880.

Welsh engineer and Professor of music David Hughes was a pioneer in microphone technology, which hugely improved Bell’s first devices from1878. Rather than patent his improvement, he published the details, making them available to all. His later work on radio waves enabled early experiments with wireless communication in the 1880s.

Later inventions

Still widely known as ‘the inventor of the telephone’, Bell had given up his interest in this invention by his early thirties. He spent the rest of his life with Mabel and their family in Canada, working on a series of varied projects including flight, sheep breeding, developing a ‘vacuum jacket’ to aid artificial breathing and the founding of the National Geographic magazine. His foremost passion remained enabling deaf people to lip read and speak, therefore blending into a hearing world. This was in itself controversial to sections of the deaf community, disenfranchising those who preferred to communicate using sign language, which they viewed as the primary language of the deaf.

Bell’s last visit to Edinburgh was in November 1920. At a speech given to pupils at the city’s Royal High School, where he had been a student 60 years before, he imagined that this young generation might live to see a time when someone “in any part of the world would be able to telephone to any other part of the world without any wires at all.”

He died on 2 August 1922 aged 75. On the day of his funeral the telephone systems in the US and Canada were silenced for one minute.

You can find out more about Bell and the history of the telephone in the Communicate gallery at the National Museum of Scotland, which tells the story of telecommunications, from semaphore to smart phones. You can also see more phones from our collection on this Pinterest board.