This summer, ten new galleries will open at the museum, showcasing the very best of our collections in applied art, design and fashion, science and technology. With more than 3,500 objects going on display, we conservators have been very busy behind the scenes getting them ready for the opening.

One of the most fascinating objects I’ve worked on is the travelling service of the Emperor Napoleon’s sister, Princess Pauline Borghese. One of the museum’s great treasures, the service was supplied by Napoleon’s official goldsmith for Pauline’s marriage to Prince Camillo Borghese in 1803.

It contains more than 100 silver-gilt items intended for washing and dressing, eating and drinking, and anything else that a lady might need when travelling. In addition to tea and coffee pots, plates and cutlery, the contents include a ewer and basin, scent bottles, combs, mirrors, toothbrushes and a tongue scraper. These are all carefully stacked and arranged inside the wooden case to save space.

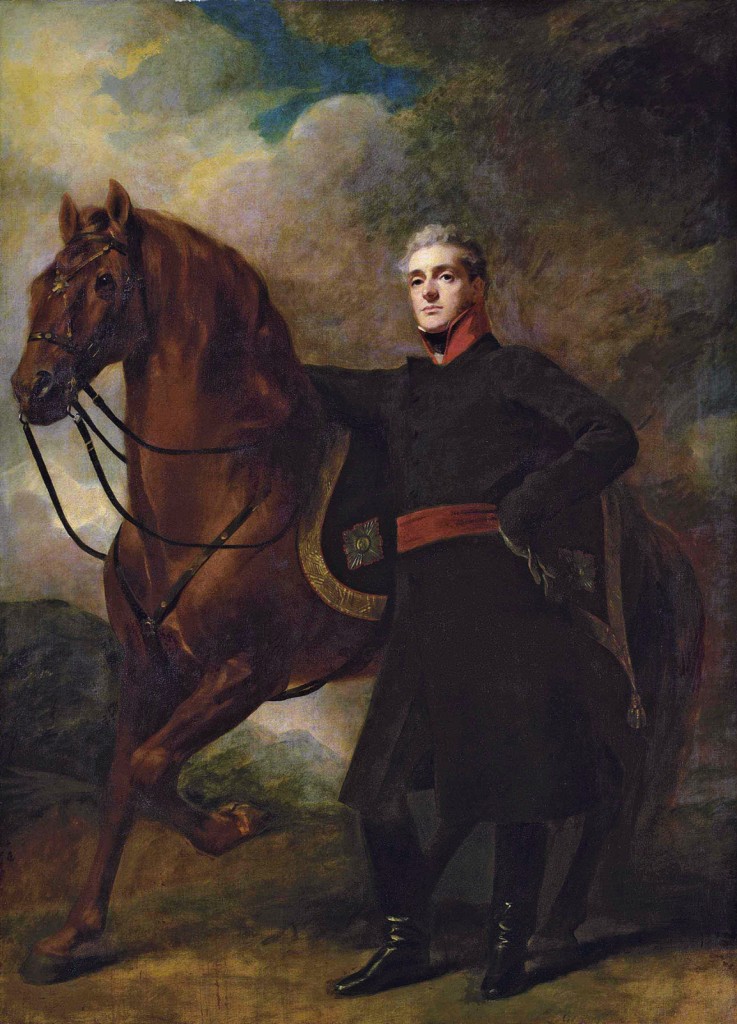

How the travelling service came to this country is interesting in itself. In 1825, Princess Pauline bequeathed the travelling service to Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton, who was a great admirer of hers. Alexander was a prolific art collector and her bequest inspired him to commission Napoleon’s former architect, Charles Percier, to produce designs for the new interiors of Hamilton Palace – the greatest powerhouse and treasure house in Scotland, until its demolition in the 1920s. The service was acquired by National Museums Scotland in 1986, with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund.

Preparing the service for re-display in our new Art of Living gallery has been one of the biggest conservation jobs of the project, requiring more than 250 hours of conservation time.

In our artefacts conservation laboratory, conserving silver-gilt objects involves cleaning surface pollutants from all surfaces and then removing tarnish (corrosion-forming silver sulphide).

With most methods of tarnish removal, however careful we are, we risk losing the uppermost layers of the silver-gilt surface during the process. We are therefore keen to reduce the need to remove tarnish again in the future. Our new galleries will feature airtight cases which include compartments with humidity and pollution controls. Keeping humidity and ultraviolet light levels low and filtering out air pollutants means that silver on display stays untarnished for potentially decades.

The starting point for display, however, is a pollutant-free silver-gilt object. To achieve this, I began by using small cloths cut from a soft, white cotton T-shirt to clean all the surfaces with white spirit, then alcohol or acetone. It’s surprising how most of the tarnish will sometimes be removed with just the very soft abrasion of the cotton, and this was the case with the Borghese service. After this initial clean, there were still some patches of thicker silver corrosion. As the gilt layer on historic pieces like the service is often thin from use, I needed to avoid using any silver cleaning products.

Instead my colleague Sophie Rowe and I used a new tool which we’ve recently added to our metals conservation kit: an electrolytic pen specially designed for converting silver corrosion back to silver metal. Unlike electrolytic reduction techniques used in the past, this pen precisely controls the whole process, avoiding the problems of micro-pitted surfaces and pollutant redeposition.

The pen has been developed by conservation specialists in Switzerland, and we are the first conservation department in the UK to have been trained in its use and application. The results are very satisfying for the conservator. When cleaning the gilded silver surfaces of the Borghese travelling service, the high-tech electrolytic pen preserved all of the remaining gilt layer and protected the silver underneath.

As a final step, each of the objects which make up the Borghese travelling service has now been safely packed away in special corrosion-inhibiting bags made of cotton imbued with reactive silver particles, until their turn comes for installation in our new galleries this summer.