During the 1970s, John Ames helped to upgrade the telephone exchange system in rural Grampian communities. Thirty years later, he visited the National Museum of Scotland and was surprised to see a very familiar piece of technology – the Glenkindie telephone exchange! Here he tells us more about working on the project.

I had never imagined that I would one day become a museum-piece, but on a trip to the National Museum of Scotland one day a few years ago I came very close! I was wandering around the technology area of the museum and was attracted, because of my background, to the telecoms exhibit. As I rounded the corner of a display case I was suddenly transported back to my time over 30 years ago when I worked in a laboratory at BT’s Research and Development centre at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk. There, prominently displayed in a large cabinet, was a piece of equipment that I had helped to develop.

I started work at BT Labs after graduating in 1972 and joined a team doing research into what was then the new technology of digital telephony. After a few years we moved more towards the development of demonstrators and prototypes and here was one right in front of my face: a small digital exchange that we had developed for use in rural communities.

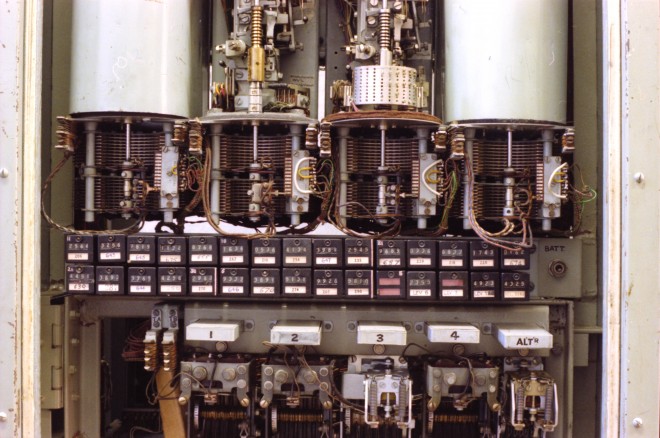

The UXD5 (Unit Exchange, Digital, No 5) at Glenkindie in Aberdeenshire was the first digital local telephone exchange brought into public service in the UK. It was intended to replace ageing small electromechanical exchanges, serving between 10 and 150 customers often situated in remote communities, especially in Scotland.

During the mid-to-late 1970s, BT was actively engaged in a huge initiative with its main suppliers to develop a digital switching system – System X – to replace the whole national network. BT realised, however, that this development would not at that time provide a cost-effective solution for very small communities.

A solution was found in the form of the Monarch Private Automatic Branch Exchange (PABX) that had been developed by BT Labs and was manufactured by two suppliers. Monarch was a digital exchange, cost-effective in just the size range needed for the small communities but it needed a great deal of modification and further development before it could be used in public service. BT Labs set about modifying the Monarch hardware and software to make it suitable for this task.

The length of a Monarch extension line might be a few hundred metres, whilst the length of some of the longest remote subscriber lines could be five or six kilometres and might easily get struck by lightning!

A completely new line interface had to be designed to feed the current needed to work the subscriber’s telephone and to survive a lightning strike, this in the very early days of the evolution of the Subscriber Line Interface Circuit (SLIC). In effect, BT Labs had to develop a SLIC for the most difficult lines before the technology had been proven on some of the shorter and better-protected lines.

Whilst Monarch was very reliable, it did not have the resilience needed for public service, where the telephone can literally be a lifeline in an emergency. The exchange is operated by large software programmes running in the exchange processor: BT Labs duplicated the hardware and software and developed the means to detect if a processor was misbehaving and to hand control over to its partner whilst also raising an alarm in the remote management centre.

The UXD5 also needed to provide information to bill subscribers and this is where I first came into the picture. I developed software to run in the exchange processors to monitor the destination and duration of every call. It would also send signals to operate mechanical meters, one per subscriber, that tick round at a rate depending on the type of call. This was an old way of charging but the first UXD5s had to be backwards-compatible with the old exchanges where the meters were photographed every quarter to give the information to work out the bill. I also developed the hardware and software that interpreted the signals and worked the meters.

Later I went on to manage a group of people who were developing the SLIC circuits; this led me to visit the Glenkindie site several times with members of the team to make electrical measurements of the variety of subscriber’s lines to inform the development process.

Manufacturing of the UXD5 by BT suppliers was organised by another part of the company and the UXD5 went on to be a huge success, serving smaller communities throughout the UK. It has proved remarkably flexible and a small team at BT Labs continued to add features and services to the exchanges as technology and subscribers’ needs evolved.

Two units from the Glenkindie telephone exchange will be on display in our new Communicate gallery, which you’ll be able to visit from Summer 2016.