- What came first, the chicken or the egg?

- Why did the chicken cross the road?

- Why am I writing about chickens?

The first two questions here are widely pondered, for either philosophical reasons or in the quest of a little humour. The latter is my own personal pondering and the answer is quite simple really… I recently went to visit the National Museum of Rural life and came away with a new-found appreciation of our feathered friends, the humble chicken.

After hopping on the ‘Farm Explorer’ to take me to the farm at Rural Life, I discovered a brood of chickens enjoying the sunshine. They were a friendly and inquisitive group, who all came close to say hello. Some brilliant facts were listed on a small sign next to the chickens and I came away wanting to know more. It’s easy to take certain common animals for granted, but here are a few of the fascinating things I discovered about the perhaps not-so-humble chicken.

1. Chickens are the closest living relatives to Tyrannosaurus rex

T.rex walked the earth 65 million years ago and was 12m in length and 6m in height. So it is quite an honour for chickens to be named as a relation, even if it is a distant one. The scientific discovery that claims there is an evolutionary link, was found during a comparison of the chemical structure of proteins within the two creatures. This fact definitely makes me look at chickens in a slightly different light, and happy that chickens haven’t evolved to become 6m tall!

2. Chickens have their own secret code

Their coding technique may not be quite as advanced as the Enigma Encoding Machine and is perhaps more of a form of language. However, if you hang out with chickens for a little while, you may start to notice that the noises they make tend to accompany certain actions. The distinct sounds they make means they share with each other what they are seeing – they even have different alarm calls for specific types of predators. This allows them to know the type of threat they face and what sort of anti-predation behaviour to perform.

3. Chickens have travelled the world

Could it be a chicken etched into the right side of this piece of slate (from the National Museums Scotland collections and dating back to 800 – 1100 AD), found in Shetland? I certainly think it could be. The chicken has a genealogy stretching much further back than that – as far as 7,000 to 10,000 years. The Smithsonian discuss here how the ‘Chicken Conquered the World’ and how the theory developed by Charles Darwin is that today’s common chicken is a domestic subspecies of the Red Junglefowl, which was native to Asia.

4. Chickens know who is the boss

In their natural habitat, chickens know their ‘pecking order’. Chickens have a very sophisticated social behaviour with a dominance hierarchy where higher individuals dominate subordinate individuals.

5. Chickens are the world’s most populous bird

Globally chickens outnumber humans 3:1, although the actual distribution of chickens per person, per country varies widely throughout the world. It’s hard to be precise about exact numbers, but according to statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organizations of the United Nations the global population of chickens in 2013 was sitting at about 21 billion. The human population of the world is estimated at around 7.2 billion (and growing).

6. Chickens come in all shapes and sizes

We should celebrate the wonderful differences between chickens around the world. They come in different sizes, from different countries and have different coloured feathers and skins. Some even have more toes than others! In fact, there are actually hundreds of amazing chicken breeds that exist around the world and about 93 British breeds. However, diversity in chickens is slipping away due to some farming techniques, so it is important that an effort is made to protect diversity amongst chicken breeds.

7. Chickens have full spectrum colour vision

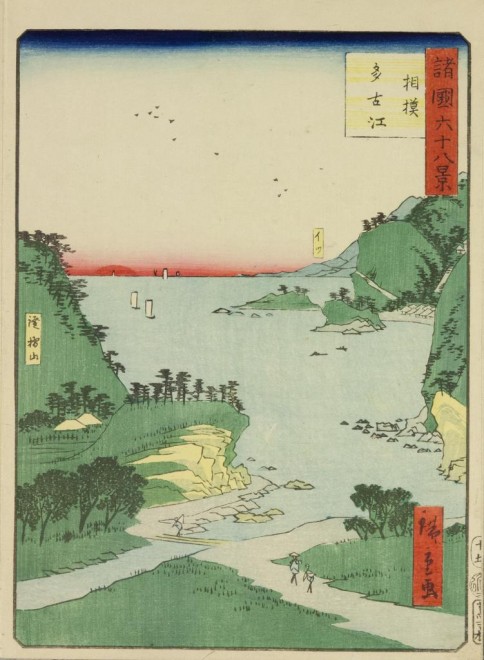

Their superior small eyes also have infra-red and ultraviolet perception, so chickens see morning sunlight almost an hour before humans, due to seeing its infra-red elements. So I imagine if there were any chickens watching this beautiful sunrise in Tako Bay, they may appreciate the beauty of the light even more than we do. This super-powered vision is linked to the structure of their eye, which maximises the chicken’s ability to see many colours in any given part of the retina.

8. Chickens are morning birds

Not ones for sleeping in, the chickens at the National Museum of Rural Life farm tend to get up early and most eggs are laid between 07:00 and 11:00. It takes approximately 25 hours for an egg to be made in the hen and hens can lay around six eggs per week. Therefore, it’s quite mind-boggling to think how many hens are laying the 32 million eggs consumed in the UK per day.

9. Chickens’ earlobes are important egg indicators

Birds eggs are beautiful and this display of various other birds’ eggs show an amazing differentiation in colour between these delicate forms. The colour of chickens’ eggs has been discussed as being linked to the colour of their earlobes. As White Leghorns, who have white ear lobes, lay white eggs and Black Rocks, with red ear lobes, lay pale brown eggs. There are some exceptions though, for example Araucanas have red ear lobes and lay pale blue eggs, and some studies have shown this link to be more a result of chance than genetics.

10. Chickens have their own Genome

In 2004, the National Human Genome Research Institute announced their first draft of the chicken Genome sequence, which was put into free public databases for research use around the world. There is an extensive resource for the chicken genome on Nature, which includes the physical map, sequence, analysis, and description of genome variation in wild versus domesticated breeds.

So I think my pondering of chickens is complete for today. I would definitely recommend heading along to say hello to all the lovely chickens at the National Museum of Rural Life. They have two different breeds: White and Black Leghorns and Black Rocks. The White Leghorn is a popular breed due to its exceptional egg laying ability, adaptability and hardiness.