One sunny but blustery day, with some trepidation, I prepared to open the first of five large wooden packing-crates that National Museums Scotland had just acquired from a private donor.

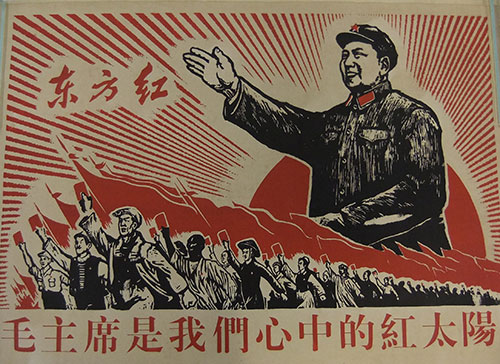

Nearly 18 months of negotiations had finally lead to a purchase aided by the Art Fund of over 500 objects relating to the Chinese Cultural Revolution, including propaganda posters, paper-cuts, paintings, magazines, copies of the Little Red Book; hand- and machine-embroidered textiles; ceramics and glassware include large figurative groups, vases and other vessels; and the contents of these five crates.

The fragile objects inside the crates had been created at the height of the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), in the famous porcelain-making city of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, south-east China. Transported hundreds of miles overland by boat, road, rail, and finally packhorse, they were stored for safety in a police station in the remote and mountainous area of Zhongdian in north-west Yunnan, part of the area now recognised as the inspiration for the literary Shangri-La. For an undetermined reason they were never distributed to their final destinations, and, for decades after the end of the Cultural Revolution, had been left forgotten and untouched until the building was destroyed in an earthquake in 1998. Rediscovered amongst the rubble, they were purchased by a collector, and were flown across continents to eventually end up with me in the museum’s quarantine room.

Some of this provenance I knew from the acquisition paperwork, but the most tangible evidence of their cultural origins was given by the original packaging inside the crates. Levering off the first crate’s lid, I found beneath crumpled brown paper a bamboo basket tied up with rope, crammed full of aged brown straw. Mixed in with the straw packaging were masonry fragments, presumably from the earthquake; also dried flower-heads; scraps of newspaper; faded Chinese characters written on ribbons; half a mouse skeleton; and what can best be described as floor sweepings. Placing the baskets side by side, I matched pairs that had altered their shape, probably during transit when they had moulded to the sides of a packhorse or pony. One had also evidently been dropped in a muddy puddle.

So what was inside these mysterious crates?! Delving into the straw (whilst wearing biohazard gloves and an industrial dust-mask) I excavated the first of over 100 small porcelain busts of Chairman Mao, or mini-Maos as I affectionately call them, untouched since they were packed during the early years of the Cultural Revolution.

They are almost all identical, although there is slight variation in the thickness of porcelain, and the detail of the moulds as they gradually wore down during production. About eighteen centimetres high, they are of a consistently high quality, moulded from very fine white biscuit porcelain and coated with a matt smear glaze, which gives them a slight luminescence. Uneducated Chinese citizens were supposedly convinced that this was because each one embodied the spirit of Mao.

Two Maos vary in that one has a different plinth, and another is half-size. Otherwise they are all the same, depicting Mao in his eponymous jacket or Zhongshan suit, with his characteristic receding hairline and prominent mole on his chin. The plinth beneath has relief inscriptions reading: 毛主席万岁: ‘Long live Chairman Mao’. Like all representations of Mao, they were produced with great care and respect. Any fault or flaw even during firing, or consequent deliberate or accidental destruction could be seen as counter-revolutionary, and the consequences for the maker could be very serious indeed, even fatal.

Along with our own British Queen, Chairman Mao is one of the most reproduced individuals in human history, represented literally billions of times in a wide range of media. During the Cultural Revolution printed material such as propaganda posters were produced in vast numbers, as were ceramic models including a variety of porcelain busts, like these examples. Officially sanctioned, they were created for distribution to official and public buildings throughout China, such as party secretaries, offices, remote schools, village police stations, etc.

Despite the distances travelled, only two were damaged on arrival, thanks to the high quality of the porcelain and the protection offered by the bamboo baskets and their padding of straw. These baskets were literally a time-capsule from that era to this, complete with smells, textures and actual dirt from the past! Museum objects themselves are often seen as tangible evidence of history; it’s rare to also get ephemeral packaging so particular to a time and a place as rice-straw harvested during the Cultural Revolution. As I unpacked the baskets I mused on the vastly different life experiences of those who had packed them about 45 years ago, of the social and political upheaval, the strict restrictions around individuality, creativity and self-expression; the Chinese intellectuals banished to undertake hard labour in the countryside; and alongside some social improvements, the subsequent poverty and suffering of the Maoist era. I really couldn’t grumble about getting a bit hot and dusty unpacking heavy boxes in a museum store!

Having unpacked all five crates, my task (with the assistance of Conservation intern Becky Kaczkowski and Collections Care Assistant Katherine Mercer) was to superficially clean the Maos with a museum-vac, repack them with conservation-grade packaging, relocate them from quarantine to permanent storage, and label each one individually with a unique accession number. Principal Curator Dr Kevin McLoughlin has been creating bilingual accession records in Chinese and English for the collection management system, which will one day be available online. Cataloguing, conservation and research is still on-going, and we hope to display at least some of the collection in future gallery displays.

As a taster a larger porcelain figurative group entitled ‘Looking up to Mao’ will be on display in the New to the National Collections exhibition opening in mid-September.

With thanks to Dr Kevin McLoughlin.