Last week saw the culmination of years of research by myself and colleagues working on the Glenmorangie Research Project on Early Medieval Scotland, in the publication of a new book on the period: Early Medieval Scotland: Individuals, Communities and Ideas.

Early Medieval Scotland was a very vibrant and sophisticated place which produced some of the most exquisite objects in National Museums Scotland’s collections. This is the time of the Picts, the Gaels, the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons and, arguably more than anywhere else in Briton, Scotland was a melting pot for numerous different ideas, techniques and styles. This fusion of ideas was helped in great measure by the big new idea of the time – the introduction of Christianity to Scotland.

This period marks the end of pre-history, with the creation of the first written texts. But that doesn’t mean that archaeology doesn’t have its own stories to tell. Very few written documents survive, giving us only a partial and fragmented picture. Almost all were written outside of Scotland, meaning they can give us a one-sided picture. They are also limited in their interest – what they record and preserve for us tends to be focused on kings, battles and deaths.

When writing our book, we wanted to take a fresh look at the period and let the archaeology speak for itself. Every object has a number of different stories to tell, depending on which questions are asked of it. Because of this we decided to look at Early Medieval Scotland at three different scales: at an individual level first, to see what surviving objects could tell us about the people who made and used them.

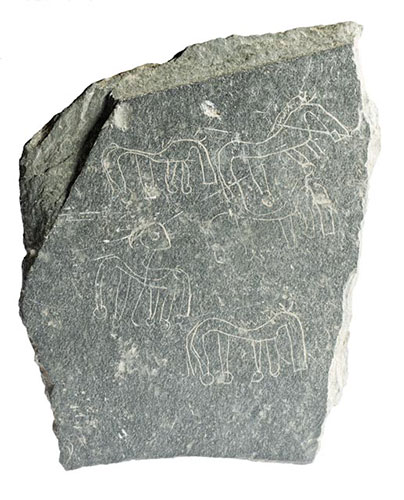

The object above illustrates this nicely: it’s a doodle of some horses scratched onto a slate at a site called Inchmarnock, off the coast of Bute. It was likely to have been made by children, perhaps in a bored moment during their monastic schooling.

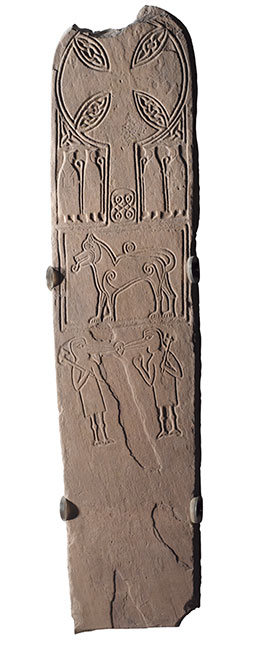

The next perspective looks at communities, thinking about the different groups of people that made up Early Medieval society. For instance, we look at Christian communities – because as far as we can tell, Christianity was the first religion to have formal and separate communities dedicated to it – and communities of craftspeople who created monuments of devotion like this piece of sculpture from Papil, Shetland (below).

Finally, we examined the bigger ideas and ideologies, the things that bound society together, and the ways in which objects were used to create and symbolise these important concepts and relationships, here illustrated by the corpus of massive silver chains (below). Massive because they are made from solid silver and can weigh up to 3 kg each: clearly these are extremely powerful objects capable of communicating big messages.

A few teasers of new research you can find in the book include the hidden symbolism and protective qualities of many elaborate gold and silver brooches, such as the stunning Hunterston brooch.

And find out why we think that a figure on the Hilton of Cadboll stone, long thought to have been a Pictish princess, may instead be one of the earliest depictions of Jesus from Scotland.

After years of research and writing, it’s a joy to see the book come to life. Its also a great opportunity to once again thank The Glenmorangie Company for their support over the last four years, without which our research just would not have been possible.

Early Medieval Scotland: Individuals, Communities and Ideas by David Clarke, Alice Blackwell and Martin Goldberg is published by National Museums Scotland and can be purchased from the online shop.

Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition is at the National Museum of Scotland until 25 February 2018 and follows three years of research supported by The Glenmorangie Company.