Construction of the coffin

The coffin base was built from many pieces of wood that were probably joined together with wooden pegs. This type of construction was typical of Ancient Egyptian coffins because of the scarcity of wood. Both the inner and outer wood surfaces were then coated with a brown mud plaster in order to smooth out the joins between the wooden pieces. A fine white gesso-like plaster was applied to the outer surface next, followed by the colourful and elaborate painted images and hieroglyphics.

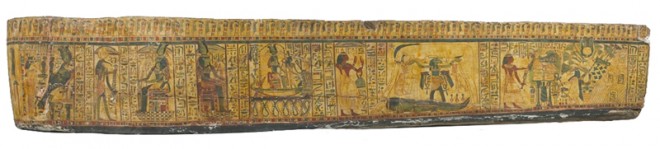

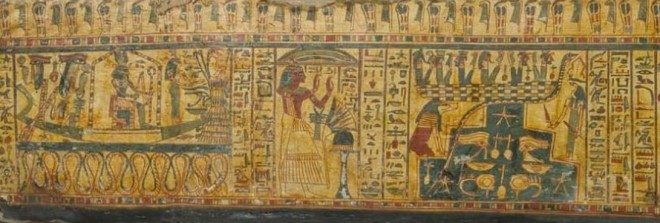

Decoration on the coffin

Although the paint on Iufenamun’s coffin base has not yet been analysed, it is likely that the red is a natural earth pigment like red ochre, while the black could be based on carbon. The blue-green colours contain a special type of pigment, which is called ‘Egyptian blue’. It is the earliest type of synthetic pigment known and is made from a glass-like substance. The pigments which make up paint need to be held together with a binding material, and plant gums such as gum arabic were often used as paint binders in Ancient Egypt. Lastly, a yellowish coating, which is probably a natural resin, was applied to the outer surface.

Damage to the coffin

Although the arid climate of Egypt preserved Iufenamun’s coffin base, it also had a harmful effect on it by permanently shrinking the wood. Because of this shrinkage, the many joins throughout the coffin’s structure have opened up and moved a bit. This has caused the layers of mud plaster and painted white plaster to crack and lift in many places and even to fall off entirely.

After the coffin was removed from its tomb, attempts were made over the years to stop the joins from opening further and continuing to move. For example, a protein-based glue was applied to the joins, iron straps were fixed to the wood across some of the inside joins, and iron screws were used to reinforce the attachment of the coffin’s base to the side walls. Areas of loss where the mud plaster and the painted white plaster had detached from the inner and outer surfaces were also filled. Modern materials such as a grey cement-like substance and plaster of Paris were used, which were sometimes painted to try to match the original decoration.

Conservation work

One of the most delicate and time-consuming parts of the conservation work was stabilising the cracking and lifting painted plaster by setting it down and securing it in place with a dilute adhesive. Knowing that the binder in the paint was probably a plant gum, a cellulose-based adhesive which would not adversely affect it was chosen to stabilise the flaking paint.

First the lifting paint was softened a little bit with a solvent and then the adhesive was fed into the cracks with a fine paintbrush. The tricky part came next as the flakes had to be carefully manipulated to re-attach them to the underlying surface without breaking them. If necessary, this was followed with the application of gentle pressure to hold them in place until the adhesive set.

The second biggest problem to be addressed by the conservation treatment was the loss of the mud and painted plasters. In many places, the broken edges around the losses were vulnerable to further damage. An effective way to prevent this from happening, however, is to fill the losses. Two types of fill materials were used: one made up of tiny glass spheres called ‘microballoons’, which are so small that they appear like a powder, and the other based on paper pulp. The advantage of these materials is that they create extremely light fills, which are not too heavy for the aged wood. Both of these fills were also held together with the same type of cellulose adhesive that was used to stabilise the painted plaster, making them compatible with the original materials used in the construction of the coffin. Once the losses were filled, they were painted to match the background colour surrounding them so that they are less obvious to the viewer.

Returning the mummy to the coffin

At the end of the conservation treatment of Iufenamun’s coffin, the mummy was to be put back inside it. Before this could happen, however, a barrier layer was made to separate the mummy from the coffin floor. This was done to protect the mummy from the iron straps which had been previously fixed across joins on the bottom of the coffin. Over time, these straps had corroded and caused some of the textile wrappings to come away from the underside of the mummy and stick to the straps. The barrier layer would stop this from happening, as well as protect these pieces of textile. It would also help to keep intact the remains of embalming resin, which had leaked out of the mummy and pooled onto the coffin floor, as well as other pieces of the textile wrapping, which had become stuck to the resin.

With the stabilisation of the damaged plaster surfaces completed and the barrier layer set into place, Iufenamun’s mummy could once again be returned to its proper resting place.