There’s nothing quite like a cup of hot chocolate. But have you ever had one from a coconut cup? Assistant Curator Dr Emily Taylor and Professor Kathleen Kennedy explore the origins and cultural background behind a ‘little cup of happiness’ in our collections – a coconut shell made into a goblet for hot chocolate.

A brief history of coconut cups and hot chocolate (Prof Kathleen Kennedy)

This small, polished coconut shell harnessed into the form of a goblet offers an example of a vital colonial American houseware that may be unique in Scotland. When the cup arrived in Edinburgh in 1956, it was just one anomalous part of a large and very diverse donation. Mid-twentieth-century cataloguers missed the larger colonial origin of this coconut cup. Properly known as a coco chocolatero, this is a style of coconut cup developed in the early colonial Americas for drinking the important indigenous beverage, chocolate.

The Spanish and Portuguese brought coconuts and coconut cups with them when they arrived in the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century. As funny as the iconic sketch in Monty Python and the Holy Grail about the viability of coconuts arriving in medieval Britain is, by 1500, the coconut cup was an old and popular form of fine dinnerware across Europe.

In fact, coconuts had been a regular import from India into the Mediterranean basin since the second century AD, along with other, better known commodities like pepper. Outside of Europe, to this day many languages retain the older name for coconut, used since Roman times: “Indian nut.” Medieval and early modern European coconut cups employed large coconut shells and generally stood on tall, handle-less stems.

In the American regions that the Europeans invaded first, chocolate was the indigenous formal beverage. It was one with its own imperial history, with taxes paid to the conquering Mexica Empire in cacao beans, and chocolate consumed only by the highest castes. It’s not surprising that the Europeans quickly adopted this American imperial drink. The Earl of Sandwich’s hot chocolate recipe for two from 1668, for example, calls for:

4 tbsp raw cacao

1 tsp cinnamon

Pinch of Jamaica pepper (allspice)

2 tbsp sugar

3 vanilla pods, removed before serving (or 1tsp vanilla essence)

Milk – to drinkers’ taste

In less than a century after c.1500, a new term appeared in colonial American records: coco chocolatero, or simply, coco, a short form that already carried the connotation of a coconut cup redesigned for chocolate. The fine dinnerware of the Europeans hybridized with American traditional foodways resulting in a new houseware that embodied colonial Latin America.

In this Americanizing process, several changes were made to the coco chocolatero design. The European coconut cup’s stem was shortened, the shells shrank substantially, and the cups sprouted small handles. Unlike European coconut cups, American smiths cast the metalwork for cocos using moulds, which they copied and shared, and so similar shapes appear again and again. Handles very like the museum’s coco can be found elsewhere, and another popular handle featured the Spanish lion.

While chocolate was enjoyed widely, local cultures influenced the form of their cocos. On our coco, the snakes may suggest an origin in present-day Mexico or Guatemala., The snakes possibly represent Quetzalcoatl, the feathered snake god of the Mexica (Aztec is a colonial name) and Maya, who was often depicted with a head that looks dragon-like to Europeans.

These ‘dragons’ raise another possibility, however. This very American coco chocolatero may also reflect the lion-like heads of Chinese dragons. For a time, the sun never set on the Spanish empire. Chinese goods, including porcelain decorated with dragons, was loaded onto Spanish ships in the Spanish Philippines, carried across the Pacific, offloaded in western ports of New Spain, carried overland to ports on the eastern coast, and then shipped across the Atlantic to Spain. Thus, colonial Spanish-American elites were just as familiar with Chinese porcelain as their European peers, and some may even have appreciated the similarity of Chinese dragons with Quetzalcoatl. Do the dragon-like creatures on this coco chocolatero reflect a Spanish-American silversmith’s impression of Chinese dragons? It’s not impossible.

As a standard utensil of the Latin American chocolate service, cocos chocolateros featured in both art and commerce. By the eighteenth century, cocos were so well-known that Mexican painter Antonio Pérez de Aguilar included one in his still life of a cupboard. Such evidence demonstrates that, along with other types of chocolate utensils, cocos made their way back across the Atlantic as chocolate spread. According to descriptions in inventories and newspapers, by the seventeenth century even English royalty owned what may well have been cocos chocolateros.

Cocos chocolateros were so tightly linked with colonization that they fell out of use as independence movements spread across Latin American in the nineteenth century. This was about the same time that coffee replaced chocolate as a preferred beverage and as an important cash crop for new nations.

Yet, for the same reason, cocos were perceived by some as historical mementos of a colonial past. Our cup is more likely to be an example of such colonial nostalgia than it is to date to the colonial period itself. Until more scholarly work on cocos chocolateros occurs, and without scientific assessment of the metal content of our coco, its route to Scotland from the Americas remains a bit of a mystery.

Entering a national collection (Emily Taylor)

We can, however, begin to understand the final leg of the cocos journey, which brought it into public ownership.

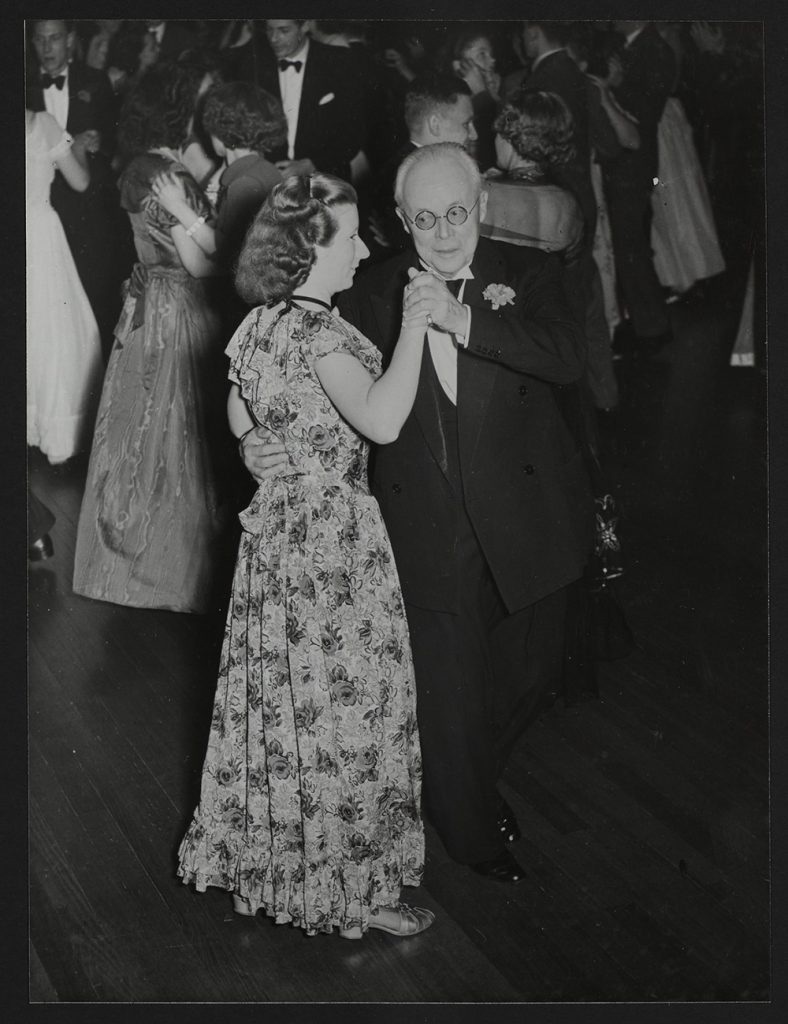

It was donated to National Museums Scotland by Sir Eric Miller (1882-1958), seen below dancing with a work colleague at an office party celebrating his fiftieth anniversary with Harrisons and Crosfield in 1949. Born Hans Eric Müller, Miller was from Darlington, the son of a German schoolmaster. After his father’s death he moved to London with his mother and sister, where he entered into the business career that defined his life. A company director from 1908, Miller was chairman from 1924-1956, when declining health forced him to reduce his responsibilities.

Harrisons and Crosfield originated as a Liverpool firm and moved to trade from London in 1854. Described by Elizabeth Ewing as ‘almost an economic commonwealth’, Harrisons and Crosfield was the parent to many companies. Sir Eric Miller held directorships of eighteen subsidiary companies during his career. In 1899, when Miller first joined the company, it acquired its first tea estate and opened an office in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata). Then came the new rubber trade, which Miller was at the heart of. He acted as secretary to the first rubber plantation company to be floated on the London Stock Exchange by Harrisons and Crosfield in 1903. One of his directorships combined new (rubber) with established (coconut) trade in the Soenqei Rampah Rubber and Coconut Plantations Limited.

The “boom in Rubber” as Miller described it to a friend in 1909, led him into close correspondence and meetings with business counterparts in Edinburgh, where there was an interest in both the technology and manufacturing. Miller swapped ideas about ‘Purub’ and ‘Coagulum’, different qualities of rubber, as well as passing on engineer’s notes to Edinburgh colleagues about the use of the Blackstone Oil Engine on company estates. It is likely he became familiar with the Chambers Street Museum during one of his business trips to the city.

We can gain some insight to Miller’s early career from letters in the company archive. Writing to a colleague and friend in May 1906, Miller stated:

“I should have replied sooner, had I had time last mail.

But that was impossible, however, as I was full up to the last & it is 8 tonight before I had time for dropping you a line. – We are still without the new offices & shall be till end of June. A beastly nuisance with all this work in hand. – My life is hardly worth living & until I can get room for some more fellows, it will continue so.”

And yet, Miller’s career is defined by a positive mindset. Elsewhere, he supportively writes, “Stick to it, & let’s hope thing ‘ll turn out well.”

From the archives we know that Harrisons and Crosfield company staff travelled, sometimes widely, in order to carry out their business. But it is unlikely this is where Miller’s coco came from. Miller became an avid collector from British dealers and auctions and a valued contributor to museum and library collections. He had a personal collection that furnished his home in Surrey and was sold after his death, but during his lifetime he contributed both directly and indirectly (such as through the National Art Collections Fund in the UK) to public collections.

Staff from the National Maritime Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum attended Miller’s funeral. But we also know he contributed to the Port of London Authority library, the British Library, the British Museum, the library at Malay House and what was then the new Malayan Museum. Miller’s colleague Sir Eric Macfayden also wrote in The Tea and Rubber Mail obituary that Miller chose to divide legacies ‘inter vivos’ after twenty-five years at the company. That is, he wanted his friends to enjoy legacies he intended for them while he was still alive.

While we are yet to find the specific origins of the coco or of its counterpart, which was gifted to National Museums Scotland on behalf of Sir Eric Miller by The National Art Collections Fund, we do know that the coco was a gift intended for public enjoyment. It was given in the spirit of Miller’s 1949 celebration speech conclusion: ‘If I ever had an epitaph I would be well rewarded if it read, in the words of the song: – ‘He spread a little happiness and he passed by’.

The journey which shaped the coco chocolatero and brought it to National Museums Scotland is undeniably one of colonial settlement, trade, plantations and business. It is also one of social ceremony and traditions of gifting across the centuries. As we delve deeper into understanding the global imbalances and legacies that colonies and plantation companies created, it is worth remembering the ‘little happiness’ of a cup designed for chocolate.