With the approaching coronation of King Charles III, Georgia Vullinghs, Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary History, has been looking at our collections of coronation material. From batons of ceremony and containers for holy oils, to souvenir cups, handkerchiefs, and biscuit tins, this range of material performs an important function in introducing the new monarch to their role.

Across history, coronations have involved a monarch being transformed into an individual who holds a unique position in society, through words, actions, and the use of special clothing and objects. Many of the rituals and objects used in the past will be seen in the coronation on 6 May 2023.

As part of the ceremony, King Charles III, like those before him, will be anointed with holy oil. This element of the ceremony emphasises the spiritual significance of the monarch alongside the secular. A gold ampulla contained the holy oil in the coronation of Charles I at Holyroodhouse on 18 June 1633. Gold was a fitting material choice for this very special liquid, which performs the function of conferring God’s grace on the monarch. It was used alongside the ‘Honours of Scotland’, the crown, sword, and sceptre, in this specifically Scottish coronation ceremony.

While the most important person in the coronation is the monarch, their presence is ceremonially announced by a series of Heralds. National Museums Scotland has been fortunate enough to have some regalia which represent specifically Scottish ceremonial positions in the coronation on loan to us. One is the crown of the Lord Lyon King of Arms. The Lord Lyon is the chief heraldic officer of Scotland, who is responsible for organising State ceremony and regulating the use of heraldry in Scotland. They are also a ceremonial ambassador or representative of the monarch.

Made by Edinburgh silversmiths Hamilton and Inches, this gilded silver coronet is modelled on the Scottish crown, incorporating a lion rampant in the top of the crossed straps. It was newly commissioned in 2003 for Queen Elizabeth II’s Jubilee and the 400th anniversary of the Union of the Crowns in 1603. The coronet (without the arches) will be worn by the Lord Lyon at the coronation, singling him out as a Scottish heraldic representative and an important participant in endowing the new monarch with their position.

This rod (or baton or wand), on loan to the museum, is a piece of the regalia of the Usher of the White Rod. While the Usher no longer conducts duties in practice, the position historically represented the monarch’s authority. The rod dates to the 19th century, around the time of King George IV’s coronation and visit to Scotland. It was made during a period of attempted revival for the role and its ceremonial importance as a Scottish component within British State affairs. The silver baton is topped with a gilded and enamelled unicorn holding a shield with the lion rampant, while the other end is formed into a thistle. These three emblems have historic association with Scotland and Scottish royalty.

In the London setting of many royal events, the regalia of figures such as the Lord Lyon King of Arms and Usher of the White Rod historically and in the present identifies the wearer as an important Scottish participant in State ceremonies, as well as serving as a reminder to the monarch of their duties towards their Scottish kingdom.

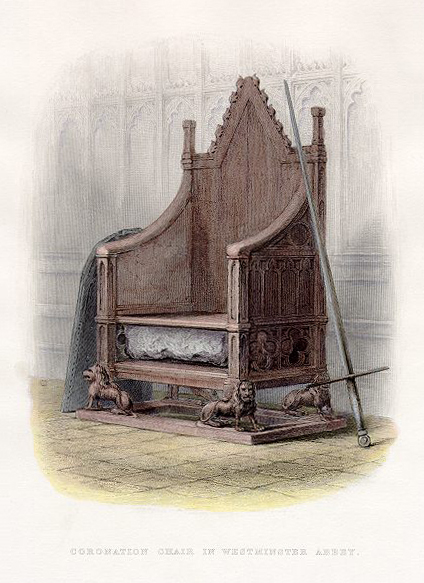

Another markedly Scottish element to the coronation is the presence of the Stone of Destiny, or Stone of Scone, within St Edward’s Chair at Westminster Abbey. This is the medieval throne sat on by English and then British monarchs during the coronation, and is still used to this day. The origin of the Stone of Destiny and its importance to the monarchs of Scotland is a much-contested area of history. What is clear is the historic and continued symbolic power of the Stone to represent Scotland, and Scottish sovereignty.

Thought to have been used for the coronations of Scotland’s early kings, it was taken from Scone by Edward I of England in 1296 in a symbolic act of subjugation of the Scottish crown. Initially an act of aggression, post 1603 when the Scottish Stuart royal dynasty also inherited the throne of England, the Stone makes for a tangible, if charged, representation of Scottish sovereignty at the moment of the monarch’s anointment and appointment.

The contested status of the Stone was heightened around the time of Elizabeth II’s coronation, after four students took it from Westminster Abbey in 1950 and brought it to Scotland. The Stone later turned up at Arbroath Abbey. Considered as a vital part of the coronation ceremony, it was carried back to its space within St Edward’s Chair in time for the 1953 coronation.

A printed silk handkerchief demonstrates the close relationship between the Stone and monarch, and its potential to symbolise Scotland’s national sovereignty at that time. Edged with a tartan ribbon, it has been printed with two motifs. One is an image of the Stone, surrounded by the words “The Stone of Destiny/Removed from Scone Abbey in 1296/Brought Back to Scotland 1950 & Chained in Westminster Abbey 1952”.

Another layer of Scottish history is added to the mix with a quote from a 19th century Jacobite revival song Will Ye No Come Back Again (which was originally written about Charles Edward Stuart or, as he is popularly known, Bonnie Prince Charlie). In the opposite corner, a picture of the Scottish crown lying on a cushion is surrounded with the words ‘Elizabeth the First/ Queen of Scots/ Second To None’. The text brings attention to the new queen as the first, rather than second Queen Elizabeth for Scotland, thus drawing a clear line between the dynastic histories of Scotland and England. This object can be interpreted as a royalist-nationalist object. It does not deny the new queen her position but makes a case for Scotland’s sovereignty to be distinguished from England’s.

The handkerchief is an example of material made in response to royal coronations. While the coronation is an important moment in investing the monarch with spiritual and secular significance, the vast majority of the public are excluded from attendance. Commemorative objects are often produced both for circulation explicitly on behalf of the Crown, as well as by independent makers and business owners. A coronation presents a lucrative commercial opportunity for manufacturers and retailers. Such objects are designed to help the public remember the occasion, and to aid their participation in the celebration and ceremony of the coronation by providing them with a little piece of it to keep for themselves.

Medals are one of the most common objects circulated in the name of the monarch at a coronation. In the collections, we have medals from Charles I’s Scottish coronation in 1633 to the most recent, Queen Elizabeth’s in 1953. A silver medal marking the joint coronation of William and Mary in 1689 demonstrates the necessity of circulating this sort of material to confirm the new monarch’s status and legitimacy, especially when that status is challenged.

Produced only shortly after the overthrow of King James VII/II, while the outcome was far from confirmed, the joint portraits of William and Mary on one side were used to legitimise their authority as daughter and son-in-law of the deposed king. On the other side, a scene from Classical mythology: Zeus striking Phaeton from his chariot, with the Latin inscription NE TOTUS ABSUMATUR (“Lest the whole world be consumed”). This was a metaphor for the role of William and Mary in striking down the Catholic rule of James VII/II, before it could run out of control, as they and their supporters saw it.

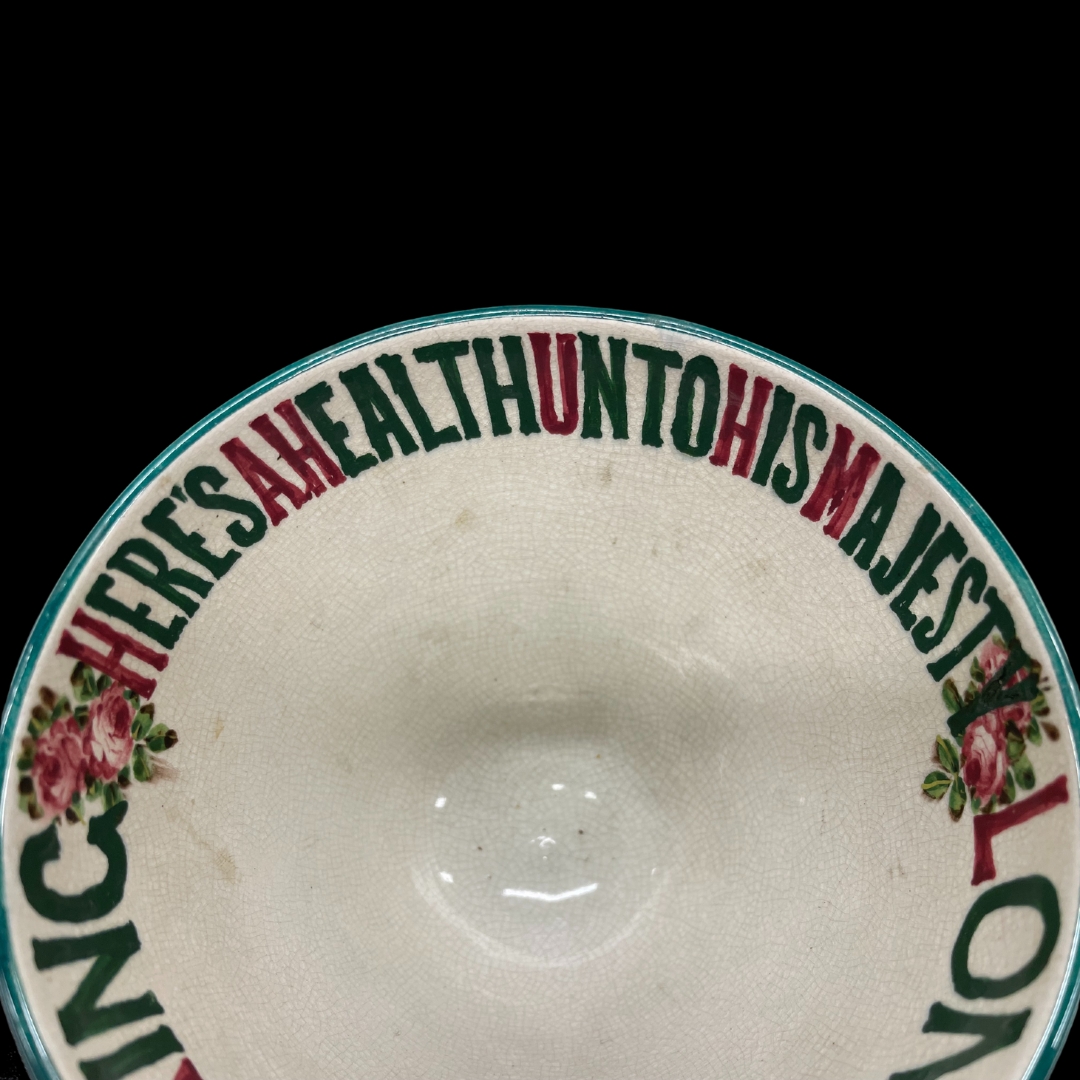

Outside of the royal court, objects are made to demonstrate support for and loyalty to the new monarch. A commemorative cup was made by the Fife pottery of Robert Heron and Son for the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra in 1902. Commonly known as Wemyss Ware, this two-handled cup is painted with the distinctive pink roses and green leaves characteristic of the pottery’s output. Thistles and shamrocks are also incorporated into the design, representing Scotland and Ireland, alongside the English rose. These flowers celebrate the united kingdoms of Edward’s dominions. Crowning the lid of the cup however, a moulded and painted thistle makes this a distinctly Scottish object, in addition to its place of manufacture.

In the centre of the cup, the crowned royal cipher of Edward VII declares his status, while a banner reads the familiar cheer “God Save the King”. On the inside rim of the cup, the user is encouraged to toast “Long Live the King” and drink “A Health Unto His Majesty”. This toast was particularly poignant as the coronation, originally planned for 26 June, had to be postponed due to ill-health of the King. It is a reminder that objects like this did not simply have a decorative purpose. They were intended to be used, filled with liquid and drunk from. Parallel to the highly sacred ceremony taking place in Westminster Abbey, supporters of the new king would say their own prayers and toasts with special objects designed to help them join in the celebration.

Similar objects are found in glass, such as a wheel-engraved goblet made in Edinburgh for the coronation in 1953. Designed by Laurence Whistler, a celebrated glass engraver, it was made for the BBC. The Queen’s coronation was famously televised, bringing a visible live coverage of the pageantry to spectators far and wide for the first time. Even with unprecedented live access to the coronation as it unfolded, objects still played an important role in bringing the coronation, and the Queen herself, into people’s homes in a tangible, durable form.

Across the country the day was enjoyed by many while savouring biscuits and sweets from tins carrying the new queen’s portrait, stirring tea with commemorative spoons, sipping from souvenir mugs. Those things helped people not only remember the day for the future, but to feel a connection with the monarch in that significant moment.

When compared to the majesty of ceremonial coronation objects, it can be easy to dismiss some of the commemorative material as tatty souvenirs. But together all these objects play an important role in confirming the status of the new monarch. While objects of ceremony are used to create an image of majesty and power, souvenirs distributed the coronation beyond the sacred space of Westminster Abbey. Through the making, purchase, and use of souvenirs, people can participate in marking the start of a new reign, and come up with their own expectations for it too. When historically and in the present, support for the newly crowned king or queen cannot be taken for granted and is never universal, these coronation objects themselves are part of a relationship between monarch and the public.