Stone steps washed with waves and selkie songs glitter in the late summer gloaming. Roaring tides sweep in from all sides to batter the shore with ageless determination, steadily devouring the remnants of cairn-raisers, Picts, Norse, and crofters with equal indifference. The west wind catches a string of hanging seashells put up by this season’s crew of archaeologists, filling the ruinous, long-silent halls with the music of the sea. Here, along the shores of the Eynhallow Sound in Orkney, eras and elements build into an unforgettable chorus. Join Digital Media Content Producer David C. Weinczok on a journey along the shores of Orkney’s Eynhallow Sound.

Rousay and the Westness Walk

Along the one and a half-mile shorescape known as the Westness Walk on the island of Rousay, time is anything but linear. Treading this sliver from one end to the other, you are hurtled through more than 5,000 years of settlements. Periods of history tidily divided from each other on paper crumble into and rise out from each other.

At Swandro, which loses a little of itself to the sea every year, Iron Age buildings are topped by a Pictish smithy and surrounded by the intermingled ruins of Norse halls, late medieval farmhouses, and cleared nineteenth century crofts.

The historical knot becomes even harder to untangle since almost everything was built from Rousay flagstone. Slabs of this extremely durable, multi-purpose stone are ready to use once pried with relative ease from their source. They proved just as useful to the people whose bones filled the stalls of Midhowe Cairn in 3,500 BC as it was for the tenant farmers who built their homes on the overlooking slopes less than two centuries ago.

A fertile strip wraps round Rousay, giving way quickly to steep slopes leading to an upland zone of heather and protruding stone. On Rousay’s southern shore the coastline is dotted at almost regular intervals with the grass-covered remains of brochs. At least thirteen of these Iron Age stone towers once lined the Eynhallow Sound, a daunting prospect for any hostile vessels and a potent expression of power for all to behold. The grandest of these ruins is Midhowe Broch at the western terminus of the Westness Walk.

In a similar string, along the very line where lowland gives way to upland (though this divide reflects modern land use) are a succession of chambered cairns with enticing names – Blackhammer, Taversoe Tuick, and the Knowe of Yarso to name a few. Explore a 3D model of the Knowe of Yarso from the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute on Sketchfab here.

Midhowe Chambered Cairn is one exception to this neat arrangement, being located on the shoreline next to Midhowe Broch. It was built around 3,500 BC, meaning that more time passed between its construction and the building of Midhowe Broch than between the broch and us today. Many of the brochs and cairns were excavated in the early through mid-20th century by George Petrie and Walter Grant, yielding a huge array of finds including human remains, pottery, animal bones of possible totemic significance, and Neolithic stone axeheads.

Bronze and iron were worked at Midhowe Broch, which – like the Broch of Gurness within view across the Eynhallow Sound – had a village surrounding the broch tower. These were not the ‘remote’ or ‘simple’ places that modern writers too often describe such places as, but sophisticated and productive centres home to imaginative, resourceful, and well-connected communities.

Though little can be said with certainty about the appearance and beliefs of Rousay’s broch dwellers, one remarkable survivor from elsewhere in Orkney gives us a rare glimpse – the Orkney Hood. It is the only complete piece of clothing to survive from before the medieval period in Scotland. Learn its story in the video below.

Westness cemetery

In 1963, Ronald Stevenson was burying a dead cow near the shore at Moaness, part of Westness, when his shovel struck something unexpected. The strange things pulled from the soil were sent to the National Museum of Scotland, who promptly sent Audrey Henshalla team to excavate. They revealed the elaborate burial of an adult woman and new-born child. Mother and child almost certainly died in the act of birth. They were far from alone – their grave was part of one the most important Viking Age cemeteries outside Scandinavia.

One of the woman’s possessions was a bead necklace, various pieces of which had Irish, Anglo-Saxon, Frankish, Frisian, and Baltic origins. Two tortoise-like oval brooches rested below her shoulders, much like those found among the grave goods of another prominent Norse woman’s burial across the Eynhallow Sound at the Broch of Gurness. The elaborate Westness brooch, made of silver, amber, red glass and gold inlay, further marks her out as someone of high status.

The long-disintegrated shawl her people buried her in was fastened by a hacked fragment of an Insular Christian shrine or book cover, modified into a brooch. As Glenmorangie Researcher and author of Crucible of Nations, Dr Adrián Maldonado, observed, she “had the whole Viking world in her grave.”

The Westness cemetery contained 32 burials dating from the seventh through eleventh centuries, including two boat burials of older Norse men. At first, these men’s graves seem to embody the popular image of Viking-age violence. Grave goods included the complete accoutrements of war: a decorated sword, a broad-bladed iron axe, iron spearhead, shield boss, and arrowheads. Both men had arthritis, chipped teeth, and heavy wear and tear in their hands. Everything suggests these were warriors who died past their prime. However, not all Norse men’s graves containing weapons are necessarily those of warriors, as these objects had wider symbolic significance and weapons buried with a person did not necessarily belong to that person.

Alongside these finds, however, were many others that cast their society in a more settled, peaceable light. In the same grave that contained the above arsenal was an iron ploughshare. Others were buried with sickles, a strike-a-light, antler combs and gaming pieces. By the 11th century, the days of marauding Vikings were, with a few exceptions, long past. The Norse in Orkney had converted to Christianity, and prominent residents of the area are named in the 13th century Icelandic saga, Orkneyinga Saga, not as blood-soaked warriors but as influential farmers. The majority of people in Viking-age Orkney would have met non-violent ends.

Indeed, the dead of Westness have at least one thing in common with modern archaeological approaches: they have little regard for tidy, binary identities. The Norse burials coexist alongside earlier Pictish burials, with no apparent attempt by the former to disturb the remains of the latter. Going much further back, new research has shown that many of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age ancestors of Orkney’s Picts were themselves incomers from Continental Europe by way of the British mainland.

Orcadian poet and storyteller George Mackay Brown, who often centred his timeless tales on Viking-age Rousay and the Eynhallow Sound, observed, “The people of Orkney today are a mingled weave.” So, too, were many Orcadians – Pict, Norse, Scots, and otherwise – of the past.

Cubbie Roo’s Castle and the island of Wyre

Across a narrow yet temperamental stretch of water from the eastern shore of Rousay is Wyre, an arrowhead-shaped island so low-lying that it seems a single high wave could wash over it.

Wyre’s population is now just five, though it was not always so sparse. For instance, excavations directed by Dan Lee and Antonia Thomas of the University of the Highlands and Islands at the Braes of Ha’Breck found a Neolithic complex containing the charred remains of Neolithic cereals dating to c.3,300 – 3,000 BC. This was probably from an extended family group living in Wyre’s western edge. Given that the family group would likely not have been alone in Wyre, and that the medieval period saw even greater activity in Wyre, it illustrates how parts of the Highlands and Islands are less populated now than at many points in history.

The most famous medieval resident of Wyre was Kolbein Hruga, a twelfth century Norseman who later passed into legend as a fearsome giant known as Cubbie Roo. In Orkney dialect, ‘cubbie’ is a word for a creel or basket-work carrier also known as a ‘cassie’. Cubbie Roo is said to have met his end when a stone causeway he was building between Wyre and Rousay collapsed, burying him in the rubble. This story gave its name to a cairn on the Rousay shore looking across to Wyre, ‘Cubbie Roo’s Burden’.

Kolbein was an innovator. Upon a small whaleback hill are the ruins of Cubbie Roo’s Castle, likely one of the oldest stone castles in Scotland. During the Viking Age, Wyre was plugged into a network of trading and raiding that reached out from the North Sea as far as the Eastern Mediterranean. The latest castle-building styles of Europe did not go unnoticed by Orcadian venturers, where they were adapted to local conditions and materials. Cubbie Roo’s Castle is now diminished to its ground floor, but would once have stood three stories high and its likely white-harled outer walls would have shone across the Eynhallow Sound.

It is likely that Kolbein had his castle built over the remains of an Iron Age broch which would have been 1,000 years old or more in his time. It’s easy to spot similarities between the castle’s layout and the Broch of Gurness, one of the best surviving broch sites located on the Mainland shore of the Eynhallow Sound.

Finds from Cubbie Roo’s Castle and immediate area around it including St Mary’s Chapel speak to use over several centuries at least, including an annular bronze brooch, fragment of chain-mail, and part of a bronze hawk’s bell. In a report on Orkney published in 1774, James Fea wrote, “The Hawks of this country are deemed the finest in the world, insomuch, that the King’s Falconer sends persons annually to Orkney, to take them up; commonly in the month of May, when they brood.” Could this bell be a legacy of this prestigious practice?

Eynhallow, the ‘vanishing island’

The Atlantic Ocean and North Sea are locked in never-ending battle in the Eynhallow Sound. This clash creates roosts, sudden and terrible chimeras of wave and wind that can sink ships in an instant. They appear as white-crested walls all around the island of Eynhallow. Once home to a monastic community and several households, the last permanent inhabitants of Eynhallow were evicted in 1851 following a typhoid outbreak.

Eynhallow is a ‘vanishing island’, often lost to sea mists and regarded in Orkney lore as the remnants of Hildaland, the magical realm of the amphibious Fin-Men who were held responsible for disappearances, fishermen’s lost catches, and other misfortunes. To again quote George Mackay Brown, he supposed that this magical realm had not been seen “since fishermen folded up their sails and installed petrol engines in their boats.”

No person could make landing on Eynhallow unless they never looked away from it and grasped cold iron in their hands, such as a nail or cruik. Such was the magic of the Fin-Men that Orcadian chroniclers insisted animals would instantly seize up and die on touching its soils. Perhaps the spell had worn off by the nineteenth century, when the island was used for summer sheep grazing.

The only inhabitable building in Eynhallow today is a ranger’s lodge. Remarkably, it contained cushions and coverings made of Morris fabrics (at least, as of the mid-2000s), brought over from Westness House in Rousay or Melsetter House in Hoy.

Yet, despite Eynhallow’s folkloric role as an island of mystery, not so long ago (in the grand scheme of things) it was not an island at all. When the first post-glacial settlers arrived in Orkney, sea levels were around twenty metres lower than they are now. Orkney was then two large islands, meaning that the first people to arrive in Rousay did not take a boat to reach it – they walked.

In our own times, the Eynhallow Sound’s waters may be fierce, but they are still shallow enough to see the bottom in clear conditions on the ferry from Tingwall to Rousay. During this short voyage you are almost certainly sailing over sunken remains of ancient human activity. Rising sea levels, resulting in large part from climate change, are a major threat to Orkney’s historic sites. Nearly 2,000 of them, including many in Rousay and Wyre, are actively being lost due to erosion and inundation.

Reflections from the Sound

It was in landscapes like these, filled with grassy mounds concealing remnants of the ancient world, that Scottish archaeology as we know it was born. The array of finds from the excavation of sites such as the Broch of Gurness, Midhowe Chambered Cairn, and Taversoe Tuick led to the recognition of Stone, Bronze, an Iron Ages, with many of them proving to be older than conventionally believed by centuries or even millennia. Investigations by members of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, founded in 1780, formed the basis of the collections of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, the precursor of National Museums Scotland.

To others, including writers, poets, craftspeople, and artists, the “mingled weave” of history on the shores of the Eynhallow Sound was (and remains) a bottomless well of inspiration. People as varied as Edwin Muir, Robert Rendall, Eliza Burroughs, and Will Self have drawn from it. Many modern archaeologists including Anna Ritchie, the late and hugely influential Caroline Wickham-Jones, and National Museums Scotland’s own Dr Hugo Anderson-Whymark have made many insights into the area and Orkney more widely. The Norse era in particular continues to inspire cultural activities in Orkney, including the St Magnus International Festival and the Orkney Storytelling Festival.

For anyone who finds purpose and wonder in the stories of the past, exploring the shores of the Eynhallow Sound as the roosts roar and seals sing, flanked by a conglomerate of sites spanning over 5,000 years, is an experience never to be forgotten. Armed with the stories and knowledge of the objects this place yielded (and, for extra immersion, a copy of the Orkneyinga Saga in hand) this landscape is unlike any other I have known. Who knows – perhaps you’ll even catch a glimpse of Hildaland through the mist.

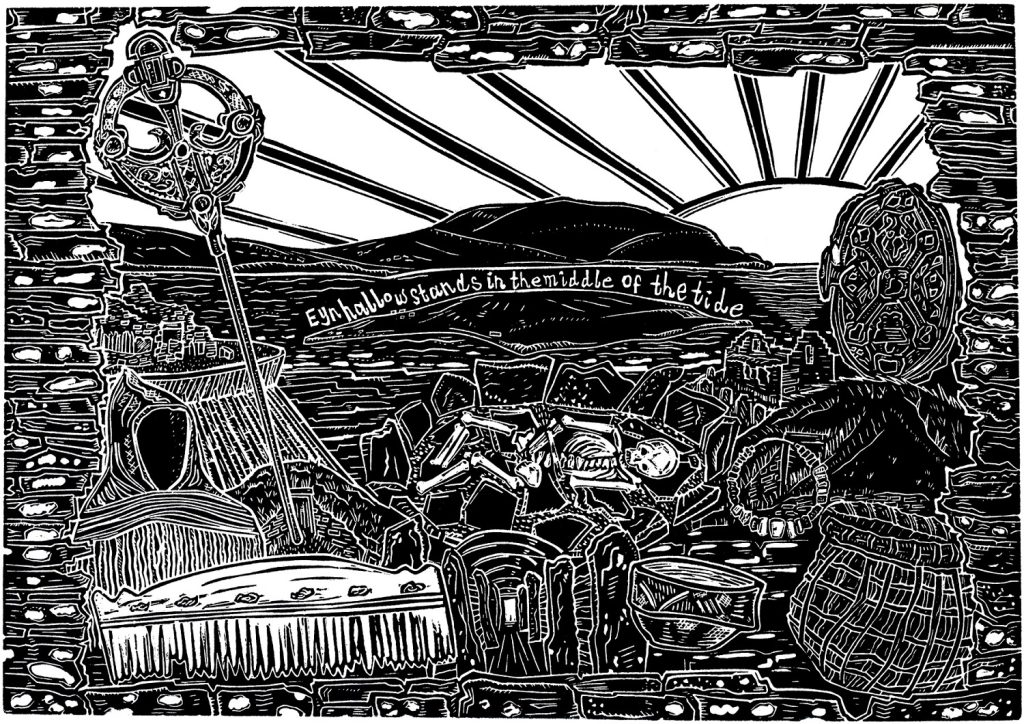

Watch the creative process of Pamela Scott, creator of the linocut, in the time lapse video below.

The six-part Objects in Place blog series will next head to Stirling, the embattled heart of Scotland. Part five will look out from the ramparts of Tantallon Castle, East Lothian, and part six will bring the series to a conclusion with a special place very close to us – Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. Dundee-based illustrator and printmaker Pamela Scott has been commissioned to produce a unique artwork for each installment. If you haven’t already, read part one about Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, here, and part two about the Eildon Hills and Melrose here.