James Hutton was a man ahead of his time. He developed a grand theory of the Earth in which he tried to make sense of a lifetime of observation and deduction about the way in which our planet functions. A leading figure in the eighteenth-century Scottish Enlightenment, his life and legacy are explored in a new edition of our book by Alan McKirdy. To celebrate, we present an excerpt.

Read the book’s Introduction below.

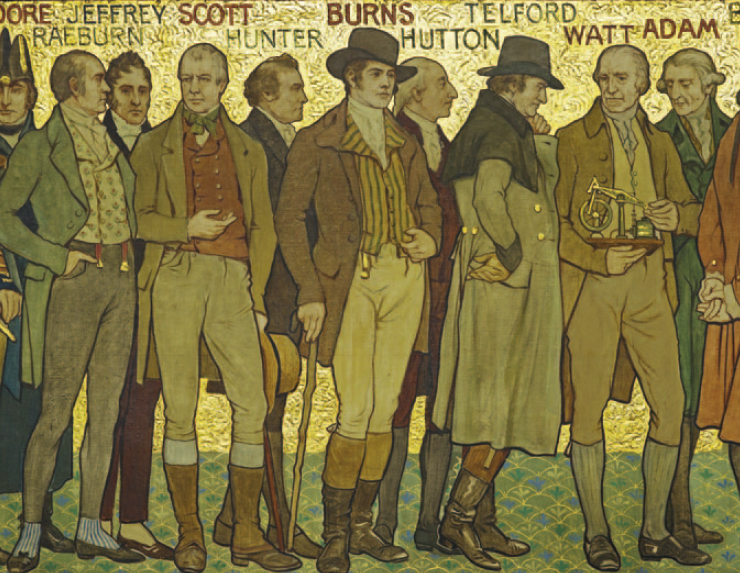

James Hutton (1726–97) came to prominence during an extraordinary period of intellectual curiosity and exploration that has come to be known as ‘The Scottish Enlightenment.’ During the second half of the eighteenth century, Edinburgh was set ablaze by men of unrivalled intellect and insight who developed ideas across an unparalleled span of subjects. Economics, architecture, literature, medicine, chemistry and, of course, geology were just a few of the areas that were touched by this prolific flowering of creativity and discovery.

James Hutton’s achievements during this period stand comparison with other scientific giants this country has nurtured, such as James Watt and John Logie Baird. Since those heady days in the late eighteenth century, Hutton’s achievements in understanding the antiquity and workings of Planet Earth have largely been forgotten. He is better known abroad than in his homeland, particularly in America, although the naming of Scotland’s premier environmental and agricultural research institute in his honour has helped greatly.

Ask Google who is the ‘father of modern geology?’ and the answer is always ‘James Hutton’. The same inquiry randomly made of most citizens of Scotland, young or old, is likely to be met with a shrug of the shoulders or a puzzled look. He deserves much greater recognition for all he achieved in so many areas. This book has been written to share with a wider audience the story of James Hutton and enable interested readers to rediscover a largely forgotten Scottish genius.

Scotland had always been a country that boasted people of intellectual achievement. Three universities were founded in the fifteenth century in the most advanced cultural centres of the time: St Andrews in 1413, Glasgow in 1451 and King’s College Aberdeen in 1495. The University of Edinburgh followed in 1582, Marischal College, Aberdeen in 1593 and the short-lived University of Fraserburgh in 1595.

This placed Scotland at the forefront of academic achievement in Europe during these times. These institutions had strong links across the continent and many scholars from Scotland worked in universities across Europe including Leiden, Paris, Frankfurt, Padua and Bologna.

By the sixteenth century, Scotland had an academic class that was vigorous, outward looking and well connected. The interchange of people and ideas between these institutions ensured that the literati, as they styled themselves, were leaders in their respective fields. This knowledge and burgeoning of new ideas was passed on to their students and all who came after them. The subjects studied in these earlier times included logic, theology, philosophy, medicine and Roman Law.

By the 1750s, around half of the male population of Scotland could read and write and most larger towns had access to a library. Education has been valued since that time as a fundamental way of improving the quality of life of the population. Schools existed in almost every parish across the land and were available, by and large, free of charge. It was the church that provided these educational facilities. Their motivation was simple. Only those who were literate were able to read the Bible. The knock-on effect of this wider population of engaged citizens meant that they could also read for themselves the new ideas as they emerged from the pens of the literati.

Against this backdrop of centuries of academic achievement, what made the activities of those who contributed to the Scottish Enlightenment worthy of the name? A period of ‘enlightenment’ almost presupposes that what went before was shrouded in darkness. There was, however, more than a grain of truth in that assumption. Up until that point, the moral authority of the Bible was thought to be unassailable. But an age of critical analysis and reason had dawned with the Scottish Enlightenment. The tramlines that religion and other forms of authority had laid down were now subject to rigorous re-examination. No matter how exalted the source, if ideas were found wanting, they were challenged by this new generation of thinkers.

The reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland had form in persecuting and even executing religious disbelievers as recently as 1697, just 29 years before Hutton was born. Thomas Aitkenhead matriculated as a student at the University of Edinburgh in 1693 and later, after studying theology, said that a belief in God was ‘a rapsodie of feigned and ill-invented nonsense’. He was indicted on two counts, the first and most important of which was that he ‘railed upon or cursed God’. Five witnesses were called who heard these profanities and no defence witnesses were allowed. For his challenge to accepted beliefs and norms, the Church ‘vigorously’ petitioned the King for Aitkenhead to be executed. His trial was quickly concluded and he was duly sentenced to death, a judgement that was carried out on 8 January 1697. Apparently, he clutched a bible in his hand when the hangman’s noose was placed around his neck. This was the last execution to be carried out anywhere in Britain for this ‘crime.’

It clearly demonstrates the iron grip that religion had in Scotland during the late seventeenth and early part of the eighteenth century and the difficulties that the emerging generation of literati and intellectuals would have in challenging years of religious dogma. This applied particularly to James Hutton as his new ideas on geology would challenge a literal interpretation of the Bible. As he looked at the world around him, he saw that nature and natural processes were the dominant force that had, and continued to, shape the landscape. Although he was a man of strong Christian faith, it seems most likely that he rejected a literal interpretation of the Bible. This meant that he had to play his hand very cleverly in negotiating sensitive issues of science and religion.

A very special aspect of Scotland’s version of enlightenment thinking was that many of the new ideas that emerged during this golden age were more of a collaborative effort than just the product of one mind. The new breed of intellectuals who inhabited the ale houses and coffee shops of late eighteenth-century Edinburgh did so in a highly socialised manner. Small groups of men, often with disparate cultural or scientific interests, met on a weekly basis. They shared ideas in a spirit of openness and candour. To illustrate the point, John Playfair, Hutton’s first and most celebrated biographer, said that John Clerk of Eldin, who was Hutton’s ‘great friend and coadjutor … through the unreserved intercourse of friendship and the adjustments produced by mutual suggestion, might render those parts indistinguishable even by the authors themselves.’

These men were geographically distant from the seat of power. With the accession of James VI and I to the throne of Great Britain and Ireland in 1603 the Royal Court departed for London. After the Union of the Parliaments in 1707, Scottish Members of Parliament left for the same destination. However, as suggested in a recent biography of Adam Smith, author of the Wealth of Nations, these Enlightenment figures were certainly not without influence. It is said that, ‘when Smith entered the room in which the Prime Minister of the day William Pitt the Younger, William Wilberforce and others were sitting, they all rose’. Pitt reportedly said on that occasion, ‘No, we will all stand until you are first seated, for we are all your scholars’. (Buchan 2006)

It was into this tumultuous intellectual world that James Hutton was hurled. He pursued medical studies at Edinburgh University, later became a successful entrepreneur in the city, travelled extensively across England and northern Europe and endured a self-imposed exile in the Scottish Borders whilst, for fourteen years, he exercised his passion for farming and agricultural improvements. Before we describe Hutton who returned to Edinburgh from these adventures aged 41, let’s rewind to the beginning of his life.

The revised and expanded edition of James Hutton: The Founder of Modern Geology by Alan McKirdy is available now. This third edition has been rewritten with twice as many pages as the 2012 edition and almost double the number of illustrations. Buy your copy from our shop to keep reading!