Funded by John Ellerman Foundation, Sue Beardmore reviewed fossil collections in museums across Scotland, documenting over a quarter of a million specimens. Scotland’s geology has played a key role in the understanding of the development of our planet over millions of years. Sue explores what our geological history can tell us about life on earth.

As the project curator investigating Scotland’s fossil collections, I expected to cover quite some distance. Looking back over the last two years, I realise I have not only travelled back and forth across the country but also through time.

I have seen an extraordinary range of fossils at 70 museums, each important in its own way. Drawn together, they tell the very long story of Scotland and the life that inhabited it over the many years of geological time. Join me on a journey through key periods during the last 500-odd million years to explore how the fossils in Scotland’s museum collections tell a vivid story of life on earth.

Claws not teeth

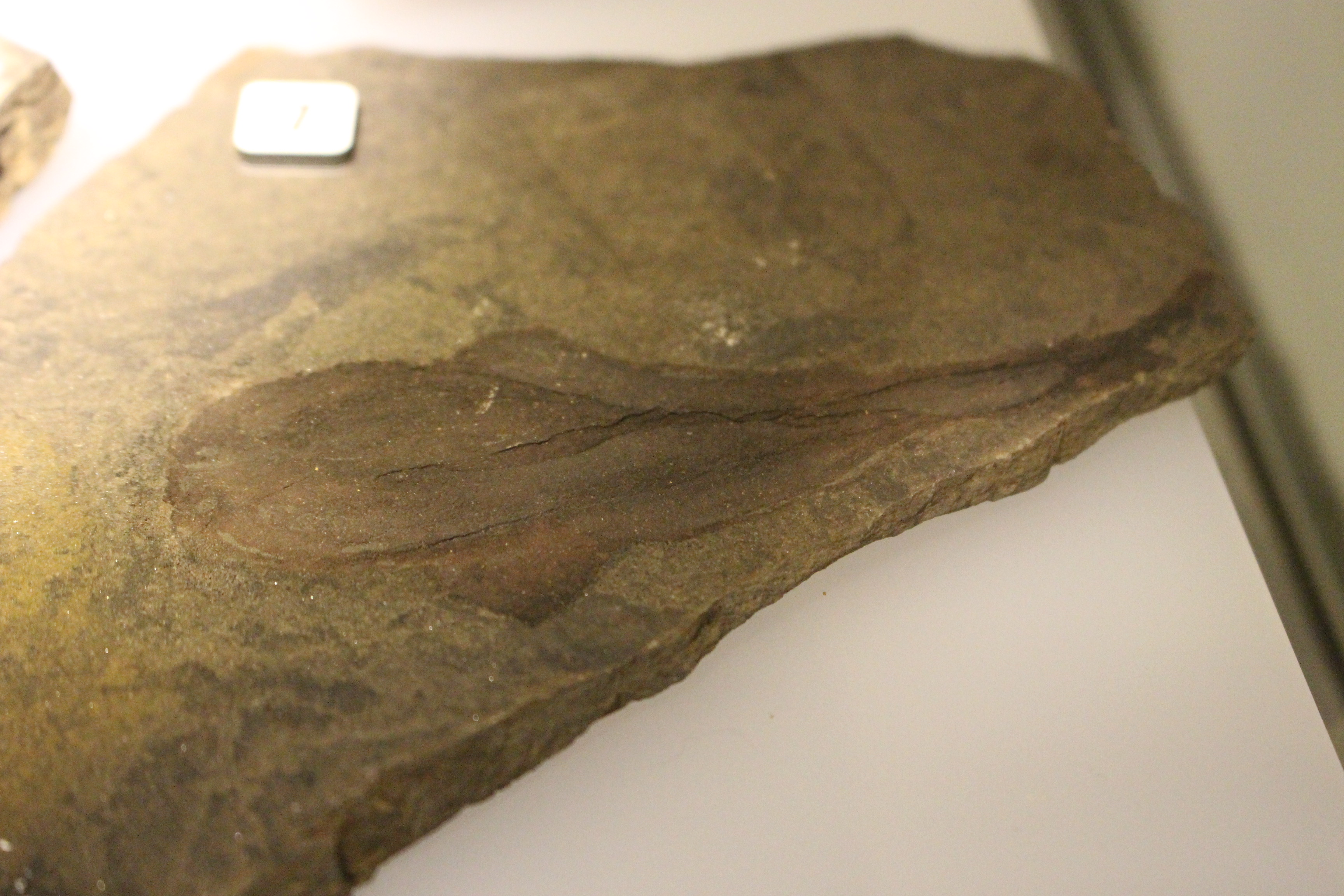

Most remarkable is the great diversity of fossils from such a long time ago. In the Silurian period (443-420 million years ago) the area around Lesmahagow (Lanarkshire) and Muirkirk (Ayrshire) was underwater. This was inhabited by primitive, jawless fish like Birkenia, Lasanius and Jamoytius kerwoodi that used suction to feed.

Also present were fierce-looking eurypterids like Erretopterus and Lanarkopterus, referred to as sea scorpions for their large claws for grasping prey. There were also pod-shrimp crustaceans like Ceratiocaris. These fossils are unique to the area and can be seen in the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

Swimming with the (Devonian) fishes

Scotland in the Devonian period (419-358 mya) was an area of dry, barren desert with fossils providing evidence of water. The Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert preserves the earliest known ecosystem with early land plants, insects and millipedes living around hot pools of bubbling silica-rich water. Much like Yellowstone National Park today, the pools occasionally bubbled over the land surface preserving everything in stunning detail. Fossils and their reconstructions from this period are on display in The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum.

The Lower Devonian of Angus was under the sea. This was where the first jawed fish, the predatory acanthodians (also at the McManus), and jawless shovel-headed cephalaspids lived alongside different types of eurypterids and other arthropods, fossilised with land plants washed in from the surrounding land.

In the Middle Devonian, a large lake system extended from Moray to Orkney with a network of rivers feeding it from Shetland. This was inhabited with the greatest diversity of fish yet: acanthodians, osteolepids, lungfish, heavily armoured placoderms and the unusual eel-like Palaeospondylus. These can be seen in Hugh Miller’s Birthplace Cottage and Museum, the McManus, and Elgin Museum. Some of the fish were widespread across Caithness, Sutherland, Orkney and Moray, telling us the river network was well connected at times. Other fish are restricted to small areas, indicating lower water levels or a shift in river channels that limited movement.

Crawling out of the water

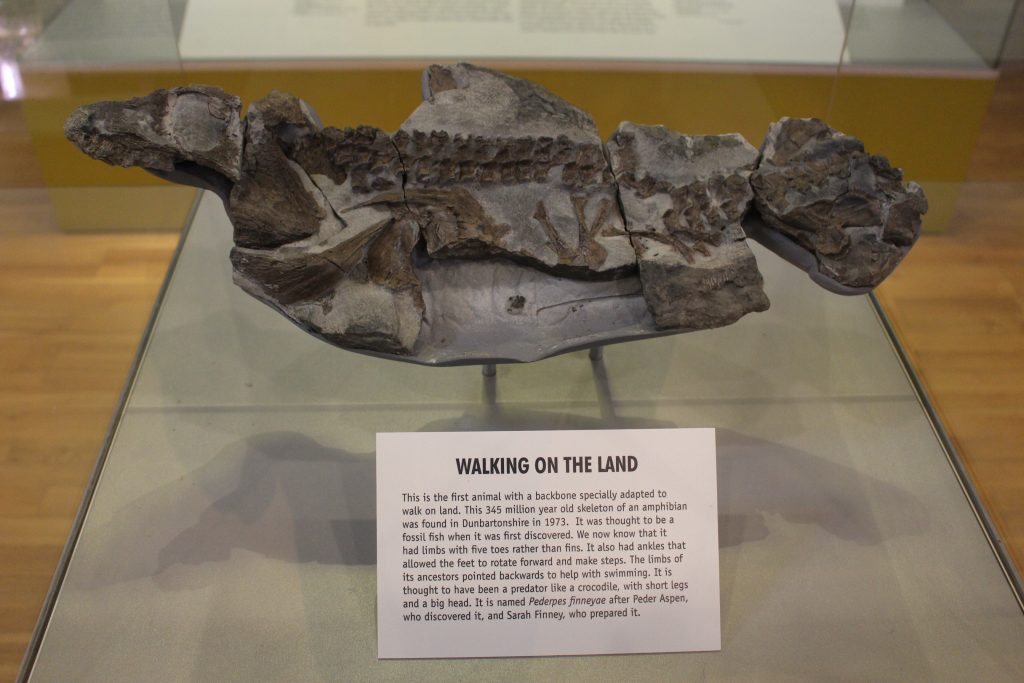

In the Carboniferous period (358-298 mya), vertebrates were following plants and arthropods out of the water onto land. How they evolved to do this was a mystery until recently, due to the rarity of rocks of this age globally leaving a 15 million year ‘gap’ in the fossil record.

It was a Harvard professor, Alfred Sherwood Romer, who identified this hole in the fossil timeline and so it became known by scientists as Romer’s Gap. No tetrapod fossils had been found dating from this missing time period, so there was no evidence to show how this giant step had taken place. But since 2008, vertebrate fossils from the Lothians and Scottish Borders have finally filled this gap. The amphibian Pederpes (on display in The Hunterian) is one of a number of lumbering animals that inhabited thickly vegetated, humid swamps.

Waves of shifting sand

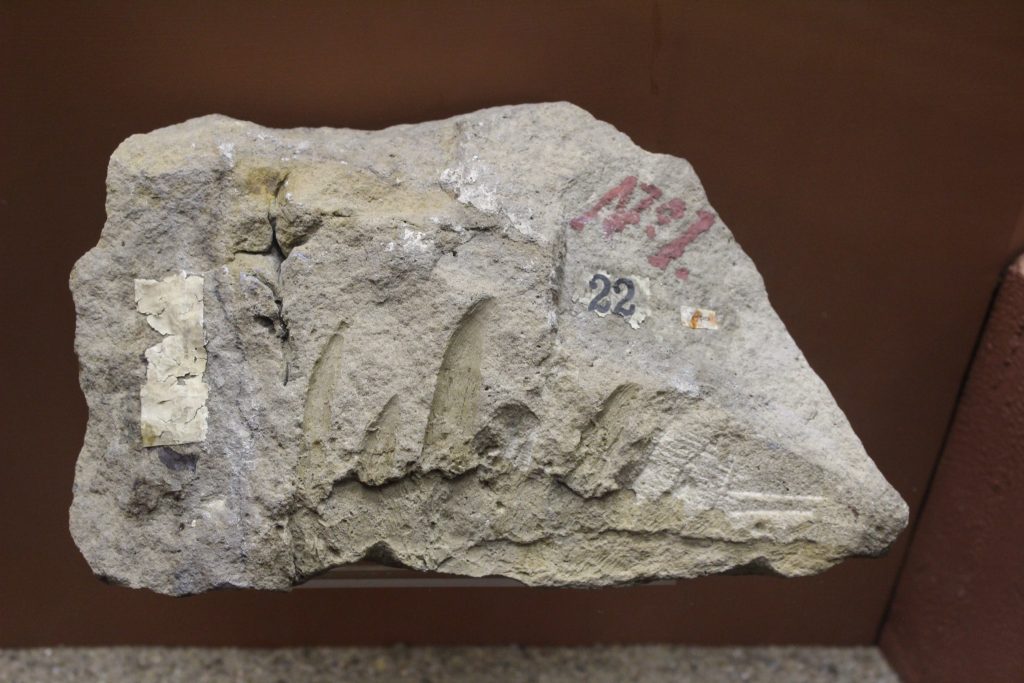

The Permian period in Scotland (298-251 mya) followed more continental collisions. The supercontinent of Pangaea that formed had a harsh and dry desert climate not particularly suited to life, let alone its preservation. Yet the Lower Permian near Dumfries and along the Moray Coast are both known for footprint and trackway trace fossils.

These are evidence of reptiles walking, running and burrowing in shifting dunes in surprising abundance. These can be seen at Dumfries Museum and Elgin Museum. Rare reptile skeletons, buried as the sand dunes migrated in the wind, are also found in Elgin Museum.

All of these animals were lost soon after, along with most of the life on the planet, in an extinction known as the ‘Great Dying’ at the end of the Permian. Relatively rapid recovery from this event is demonstrated by the diverse ‘Elgin reptiles’ from the Triassic of Moray (Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum).

The discovery of land reptiles and fish that live in water in what seemed like the same sandstone rock was proof of deposition in more than one interval of geological time. The fish in the Old Red Sandstone (Devonian), and reptiles in the New Red Sandstone (Permian-Triassic). Thomas Huxley, who studied these fossils, used this as evidence for the then-new theory of evolution.

Walking with dinosaurs

Fossils from the Jurassic period (201-145 mya) demonstrate a rare glimpse of a terrestrial Middle Jurassic estuarine environment. One where herbivorous and predatory dinosaurs wandered in search of food. They left trackways in soft mud and the various shapes and sizes can be seen in displays at the Staffin Dinosaur Museum and The Hunterian.

Some of the footprints represent the earliest evidence of dinosaurs in Scotland. Their bones, the first actual evidence, have been found with well-preserved turtles, crocodiles and small mammals from the same time. With recent discoveries elsewhere along the northwest coast, there is still more to find from this particular window.

Plants in lava

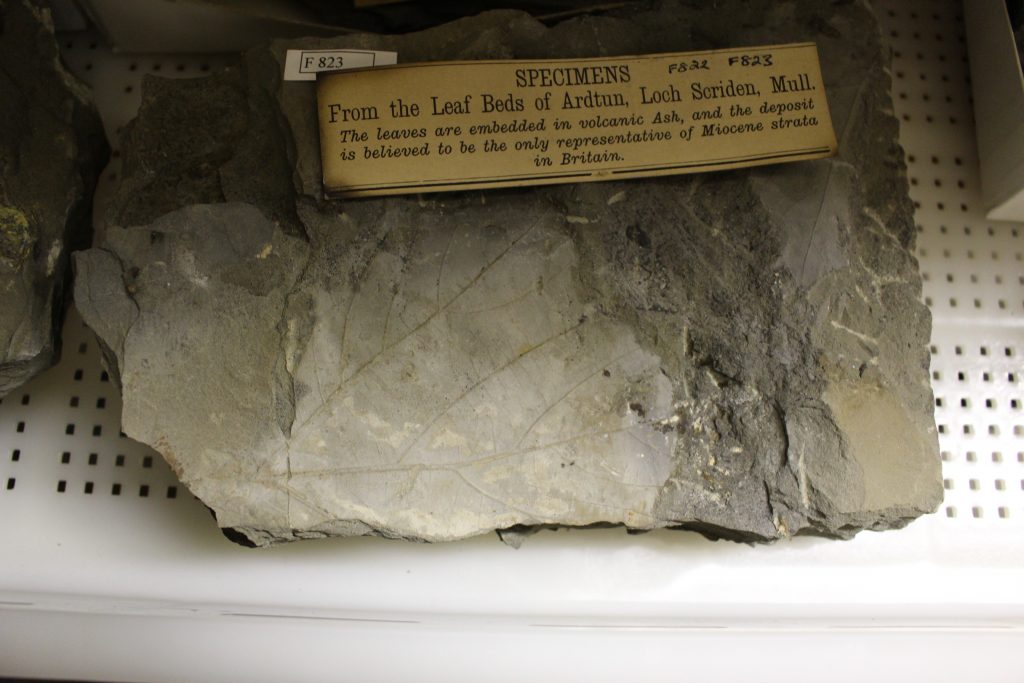

The next phase of Scotland’s history is one of explosive volcanic activity as the North Atlantic opened. A rare and important discovery was the Paleocene period’s (66-56 mya) Ardtun Leaf Beds on the Isle of Mull. Leaf beds are a layer of leaves that somehow survived the heat of lava and ash. Discovered by Lord George Campbell, Duke of Argyll, these found their way into museum collections. The charred remains of trees, one of which is known as MacCulloch’s tree, can still be seen on the island itself.

Cold as (glacial) ice

The final stop on our journey, the very top of this geological stack, are the 13,000-year-old Arctic clays, found along the Tay and Clyde Estuaries. Fossils include molluscs (bivalves and gastropods), fragile brittle stars, barnacles and microfossils (ostracods, foraminifera) as well as rare vertebrate bones from seals and an eider duck. They can be seen in Bute Museum, Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Montrose Museum and the McManus. Studies of the fossils and clays document the northward shift of cold zones as glaciers retreated after the last Ice Age and are still very relevant to climate change today.

Fossils in Scottish museums cover so many more intervals of geological time and there are as many specimens from around the world to look at. It would take me at least another 50 blogs to even begin describing them, but it’s way more fun for you to follow in my footsteps.

Visit the museums dotted across the mainland and islands of Scotland for yourselves and see fossils and geology more widely on display. Happy hunting!