A pair of women’s shoes, dated c.1730-1760, came into Textile Conservation to be prepared for display in our Fashion & Style gallery. They are intended to replace a pair of 18th century shoes that are currently on display.

This is an example of best practice known as ‘rotation’ in the museum world. Not all objects in the museum can be on display forever as it can affect their condition, so it is the job of Curators and Conservators to work together to identify how long a particular object should reasonably be on display for, and if there is a similar object in our collection that could replace these objects without changing the entire story of the gallery.

To preserve our objects, we must carefully consider each object’s material and its fragility to determine how long the object can be on display for. We sometimes use scientific analysis, such a light fade testing, to help make the decision.

Since these ‘rotation’ objects do not have as strict a deadline, like an exhibition would, we tend to work on them alongside other projects and at a slower pace. This can sometimes mean that we have a little extra time to carry out more in-depth research and analysis of the object and their materials than we normally would. This was the case for these shoes.

X-ray analysis

When my colleague Rosie wanted to find out what material the heel of a pair of shoes she was conserving were made of, and what insect might have made the small holes in it, it was a perfect opportunity to do the same with my shoes and compare them in terms of material and manufacture.

We decided a good place to start was with the x-Ray facility at the museum. We hoped that this could give us a closer look at the materials and all their layers.

Unfortunately, the x-ray analysis of my shoes did not reveal any new information about the materials and their different layers. It did show that there was no pest damage in the wooden heel and gave some beautiful images of the metal thread decoration.

Microscopy Analysis

The damage and holes to the inner silk lining fabric enabled me to view and document all the layers that made up the shoes between the outer pink silk fabric and the silk inner lining fabric. The outer pink silk fabric was backed with a heavier, open weave linen fabric. The metal thread decoration is embroidered through the outer pink fabric and this heavier linen fabric. Then there was a mystery layer which was not woven, but appeared at first to look like a soft, fine kid leather. And then finally the silk inner lining fabric.

On closer inspection, using the magnification from a linen counter, it was felt that the inner material was not kid leather, as it appeared more like paper. However, in consultation with our Paper Conservators, they felt that although it had paper-like qualities, it was not clear that it was paper. Further analysis was needed to get a closer look at this material!

We are very fortunate at the National Museum Scotland to have access to a fabulous stereomicroscope that I could use to get a closer look at this material.

Unfortunately, due to the three-dimensional nature of the shoes and the limited access to the material behind other layers, the images from the stereomicroscope, although better and closer than with the magnification from a linen counter, did not reveal anything further. It still looked a lot like paper. I needed magnification that was a bit more powerful!

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis

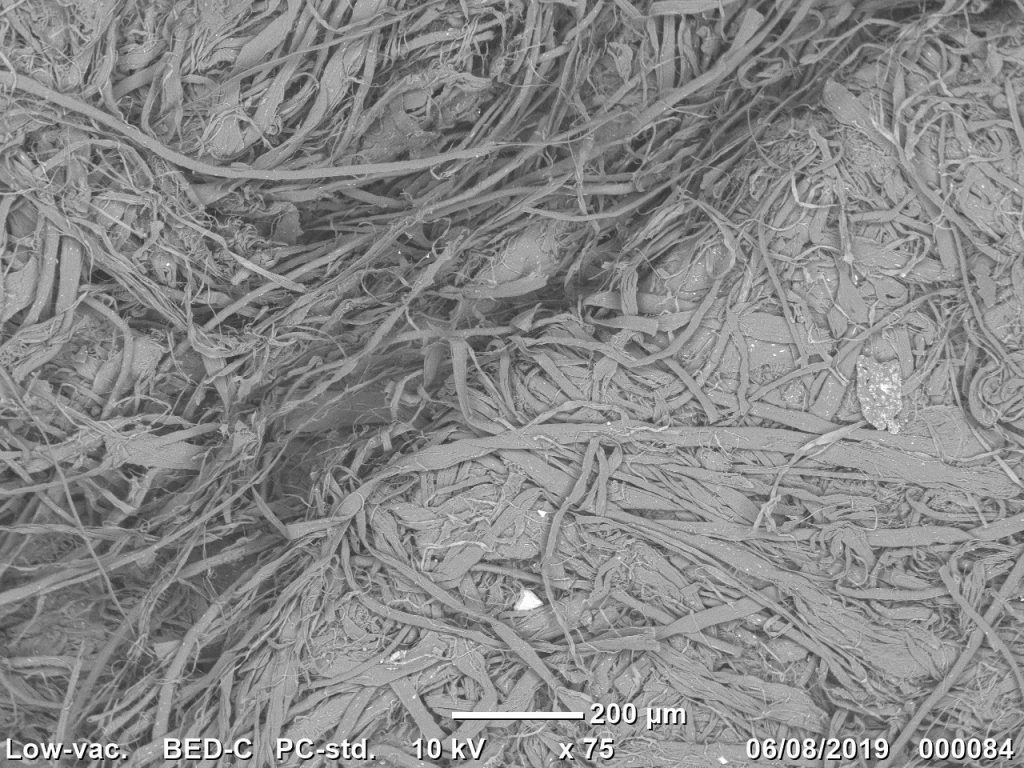

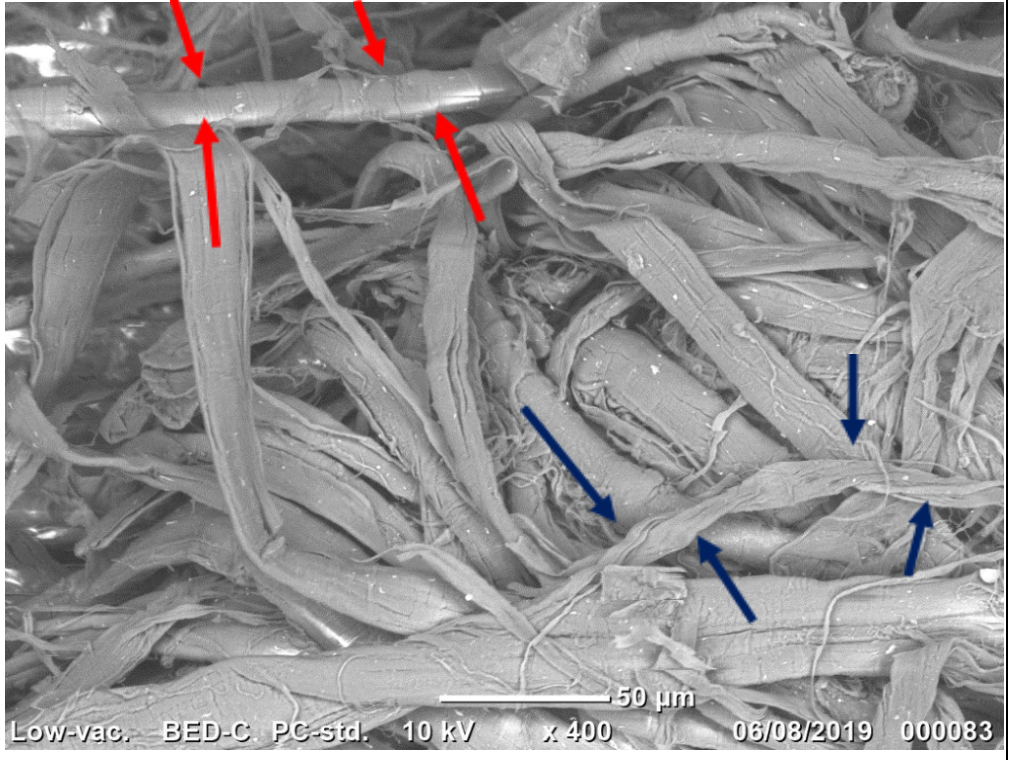

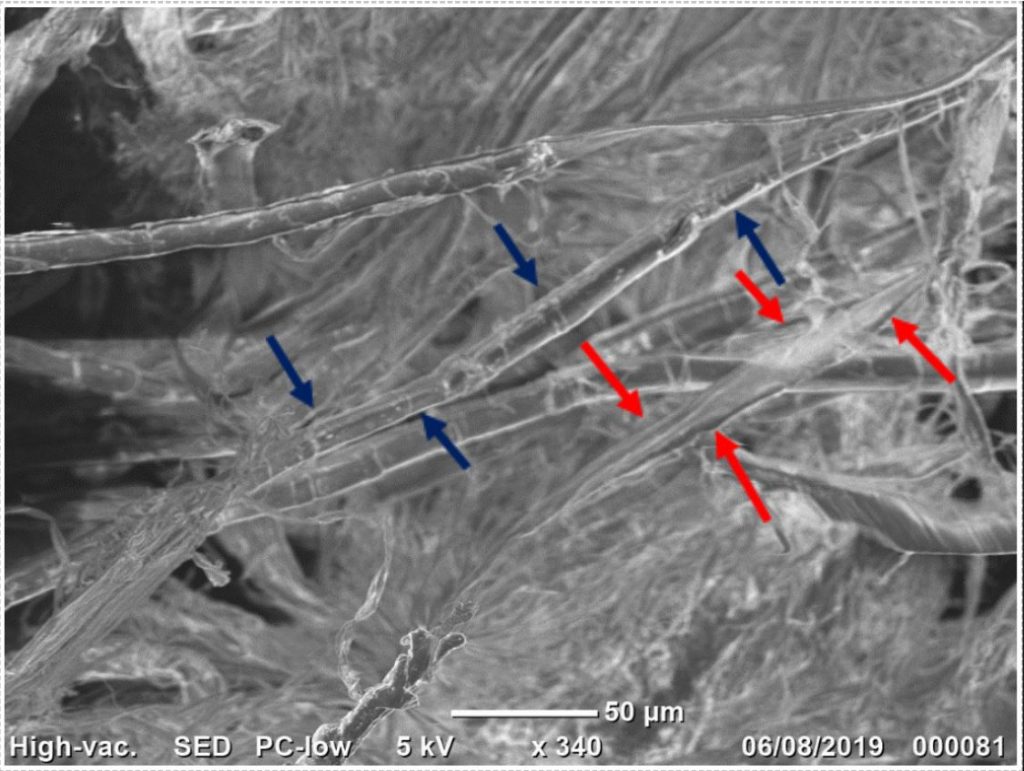

I managed to take a small sample of the material which I was able to have analysed with the use of a scanning electron microscope (SEM). This method of analysis gave some amazing images, and really showed what I was looking for.

The images above are from the SEM, from them I can see that the material is made from two different fibres. Cotton – the fibre that appears flat and ribbon-like with twists along its length, and linen which is smooth and bamboo-like with nodes across its width.

The presence of these two fibres combined to make a material suggests that the mystery inner layer is something known as ‘rag paper’. This is where waste material and off cuts from the textile industry were combined to make a new material, rather than the cotton and linen being thrown away and wasted. What a discovery!

If it hadn’t been for the additional time afforded for analysis and research, and the damage to the silk inner lining that allowed me to take a closer look and material sample, we would have never known that there was this additional layer inside the construction of the shoes, let alone what it was made of. This information is invaluable to the story of the shoes and their manufacture, as well as their care and preservation in the future.

This is part one of a two-part blog — look out for the second part where we show you the conservation and the mounting of the shoes, finished and ready for display.