As an Artefact Conservation Intern for National Museums Scotland, I’ve had opportunities to conserve many types of interesting objects. One of my favourite projects was the Dan Klein Glass Conservation Project, where I worked on the conservation of four glass artworks from the collection, each with their own unique issues that presented interesting challenges.

I was able to communicate with the artists about three of the objects, which was a significant learning experience. Consulting with the artist allows the conservator to understand the intention of the artwork so that an appropriate treatment can be determined. Sometimes, to preserve the integrity of the piece, interventions that would normally be considered too drastic for archaeological or historical objects are approved by the artist.

Form

The first object that I conserved was Form by Galia Amsel, created in London during the 1990s. It consisted of three segments of cast and sand-blasted glass that created a large curved shape. Unfortunately, one segment was broken into multiple fragments that varied in size from small to large shards.

There were small cracks all over the surface of the glass segments and they were covered with surface dirt, some of which had become embedded in the cracks. Since I was unsure about whether or not these cracks were intentional or had appeared over time, I contacted Galia Amsel to ask about them.

It turned out that the cracks were a result of the manufacturing technique. She confirmed that the embedded dirt must have accumulated over time and was not meant to be there. Therefore, it needed to be removed. I couldn’t efficiently remove the dirt that was embedded in the cracks manually, so I decided to try steam cleaning. After testing a small area and determining that it was very effective and safe, I steam cleaned the object. The inner circle segment was too fragile for steam cleaning, so instead I swabbed it with de-ionised water and used a stencil brush to remove most of the embedded dirt. Removing the dirt greatly improved the object’s appearance.

Reconstructing Form was difficult because the fragments were large and heavy, and I decided that a thin, clear epoxy resin would not be the most effective adhesive. Instead, I used Paraloid B-48N, an acrylic solution to reconstruct the fragments. Paraloid B-48N is a very strong adhesive that would support the weight of the glass while still being removable. For additional structural support, I adhered strips of Japanese tissue paper along the joins on the back of the glass using the same acrylic resin.

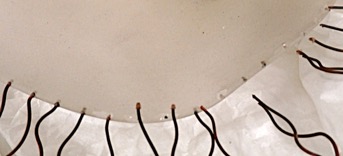

Verve

The next artwork was Verve, created in 1996 by Linzi Hodges. It was manufactured from slumped glass and copper wire. In addition to the thick layer of dust and dirt that covered the object, the main conservation issue was the separation of the copper wires from the glass. There was also evidence of copper corrosion on some of the wires.

I began the treatment by cleaning the glass with de-ionised water using a swab and stencil brush. I then cleaned the copper wires by swabbing them with solvents, which removed the copper corrosion products.

However, Verve was a challenging piece to conserve because the artist had put the copper wires into very shallow holes in the glass and twenty-nine of the wires had detached, often breaking off small glass shards around the holes. Two of the copper wires had separated from the frame completely.

I didn’t use an epoxy resin to re-adhere the wires since it would be too thin to support them during the long curing process and would have been very hard to remove, which may have caused the wires to break if mishandled in the future.

Instead I decided to use Paraloid B-48N adhesive because it was strong enough to hold the wires, matched the translucency of the glass, would cure quickly and was viscous enough to act as a replacement for the missing glass shards around the holes.

While re-adhering the wires, I struggled to support them in the holes while the adhesive cured. I consulted my supervisor Stefka Bargazova, who showed me a technique that uses cotton tying tape and bamboo skewers to create tension and hold curved objects while curing. This technique helped me to adhere the copper wires into the glass and recreate the original shape of the object.

After the adhesive had cured, I removed any excess by cutting it with a scalpel or swabbing it with solvents to soften and then remove it.

However, the conservation of an object does not stop once the treatment is completed. In order to ensure its future preservation, this object needs to be handled with particular care. I left clear instructions in the object’s storage box and on the museum’s database that moving the copper wires should be avoided. When handling, the glass must be fully supported from the base and no pressure should be applied to the copper wires, as this will cause them to detach.

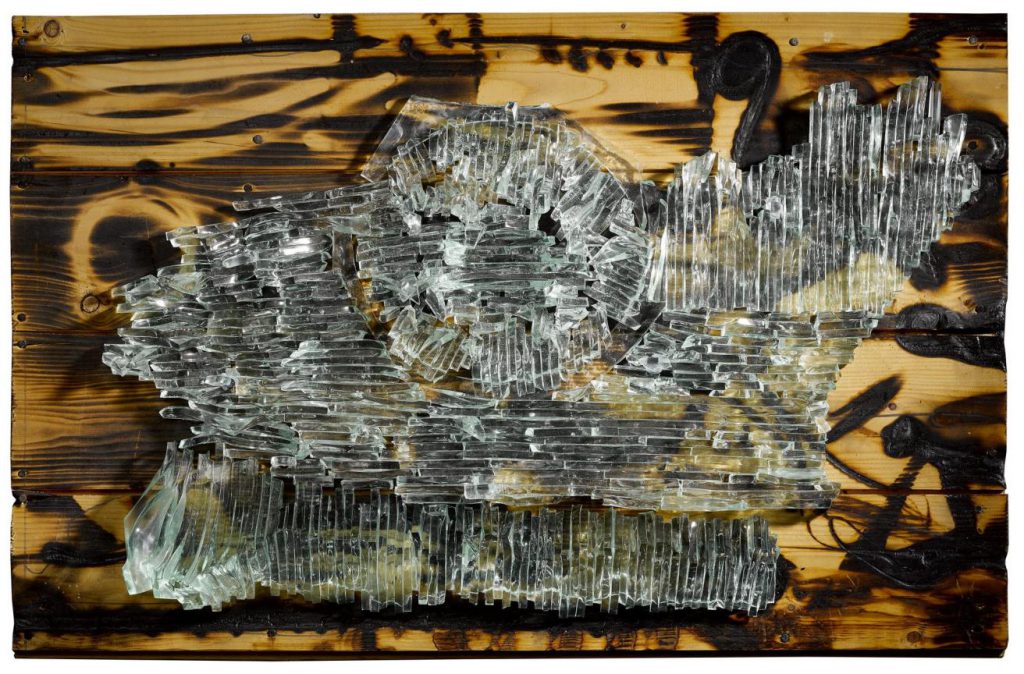

Wall Piece

The third piece that I conserved was Wall Piece by Matt Durran, which was created in 2004 in Lybster, Scotland. The work consists of glass shards that have been adhered onto scorched wood in a shape that suggests a coastline. The primary conservation issue of this piece was a detached section of the glass shards at the bottom of the piece. There was also surface dirt on the glass and wood.

Although it appeared to be a straightforward clean and reconstruction treatment, Wall Piece proved to be more difficult than expected. Since the broken glass section was quite heavy, re-adhering the fragment along the one broken join would not support its weight, especially if it is ever to be displayed.

I had two options to support the weight of the glass section. The first was to re-adhere the glass onto the wood using a cast sheet of adhesive. The second option was to use a mounting bracket, which would require drilling into the wood. At this point, I consulted with the artist Matt Durran about whether he had a preference for either option. He was not concerned about introducing an adhesive or drilling into the wood and left the final decision up to me.

I then consulted with our mountmaker, who told me that making a bracket to support the glass that did not visually detract from the piece would be very difficult. I determined that devising an appropriate mount would take too long and be too costly. Also, even though Matt had approved the drastic intervention of drilling into the wood, I decided against this option to preserve the physical integrity of the object. Therefore, using an adhesive was my best option.

Casting a sheet of adhesive rather than applying it in liquid form would allow me to control its application better and to avoid accidentally applying it to other areas of the glass and wood.

I began the treatment by cleaning the wood and the glass using a brush and vacuum. I then swabbed the glass with de-ionised water to remove any accretions. Once cleaned, I re-adhered the glass section along the join using Paraloid B-48N, an adhesive which I selected for its strength. I did not want to risk using an epoxy resin since, due to its low viscosity, it would likely have accidentally seeped into the wood and consolidated it.

As planned, in order to further strengthen the re-adhered section and ensure that it did not detach at a later date, I cast a sheet of the same adhesive. I then cut and inserted segments of the adhesive sheet underneath two small areas of the re-adhered glass section. I had previously coated the wood in these areas with Paraloid B-48N to allow it to stick strongly to the cast adhesive. I re-activated the sheet adhesive using solvent to allow it to adhere to both the glass and the wood.

Finally, once it was reconstructed I noticed that there was a very small glass segment that was missing along the top of the re-adhered glass section. I used modelling wax to take the shape of the small area that had been lost. I created a one-part mould using silicone rubber and then cast the shape with Hxtal NYL-1 since the low viscosity of the epoxy resin would make it easy to cast and the resulting fill would be clear and look like glass. Once cured, I used a Dremel and Micromesh to shape and polish the fill. I adhered this between the re-adhered glass and the section above it, again using the 50% weight/volume solution of Paraloid B-48N in acetone, to fill the missing area and act as an extra contact point to further support the weight of the glass.

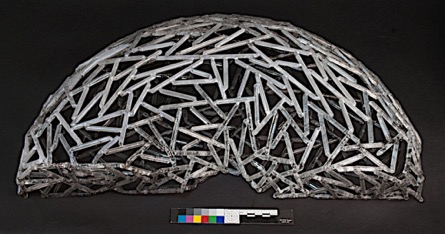

Hielo

Finally, the last piece that I conserved was Hielo by Lesley Wildman, which was crafted around 2000 in London. The artwork is a circular piece that consists of two halves, one manufactured from lampworked borosilicate glass rods and the other from metal. The glass was very dirty and one glass rod had detached. The metal section was also dirty and had some surface abrasions.

Hielo also required me to confer with the artist. Initially, the dirt on the glass appeared to be superficial. However, when I began cleaning it by swabbing the glass with de-ionsised water, I discovered darker accretions on the rods that required a significant amount of effort to remove. I didn’t think that Lesley Wildman had intentionally included them, but I wanted to confirm this so I emailed her and asked if she had any idea how these accretions may have formed. She informed me that she didn’t know and that they were not part of the original artwork. They may have formed over time as a result of a chemical process initiated by the manufacturing procedure or poor storage conditions. Thus they should be removed if possible.

To do so, the glass was immersed in a bath of de-ionised water and some of the accretions were gently scrubbed off with a stencil brush. After this, I swabbed them with de-ionised water to remove some of the remaining accretions. I removed as much as I could, but some were impossible to reach effectively, particularly along the joins. I cleaned the metal half of the object by swabbing it with solvents.

More often than not, conservation treatments do not go exactly as planned and must be adjusted to fix unexpected issues. While cleaning Hielo, four additional glass rods that were already fragile became detached from the object. All five glass rods were re-adhered using a 50% weight/volume solution of Paraloid B-72 in acetone. Any loose glass rods that were still attached to the object were consolidated using the same grade adhesive.

Most conservators would probably agree that they tend to be perfectionists, so this object was the most frustrating one for me to work on since I wanted to remove all of the accretions. Unfortunately, this was not possible and I will have to accept that I achieved the best possible result. Most importantly, the object is stable and will remain so for years to come.

Overall, I am pleased with the conservation treatment results for all of these objects. They have all been stabilised for future preservation and their aesthetic appearances have been improved. These treatments allow the original intention of each piece to be communicated to viewers. I have learned a great deal about contemporary glass conservation through this project. In particular, I was able to consult with the artists and determine the best treatments for the objects. I then applied my conservation ethics knowledge to make treatment decisions that preserved the integrity of each object.

I am currently working as a contract conservator at The Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) where I continue to apply the skills and ethics I’ve acquired while working at National Museums Scotland.