In 1999 a Bronze Age spearhead was donated to the National Museums Scotland collections by Professor Charles Thomas on the occasion of his Rhind Lectures for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the spearhead. It has a socket for inserting the shaft and a loop on each side for securing the shaft with binding. This style was very common around three and a half thousand years ago (1400–1100 BC: the Middle Bronze Age).

The Chisholme spearhead

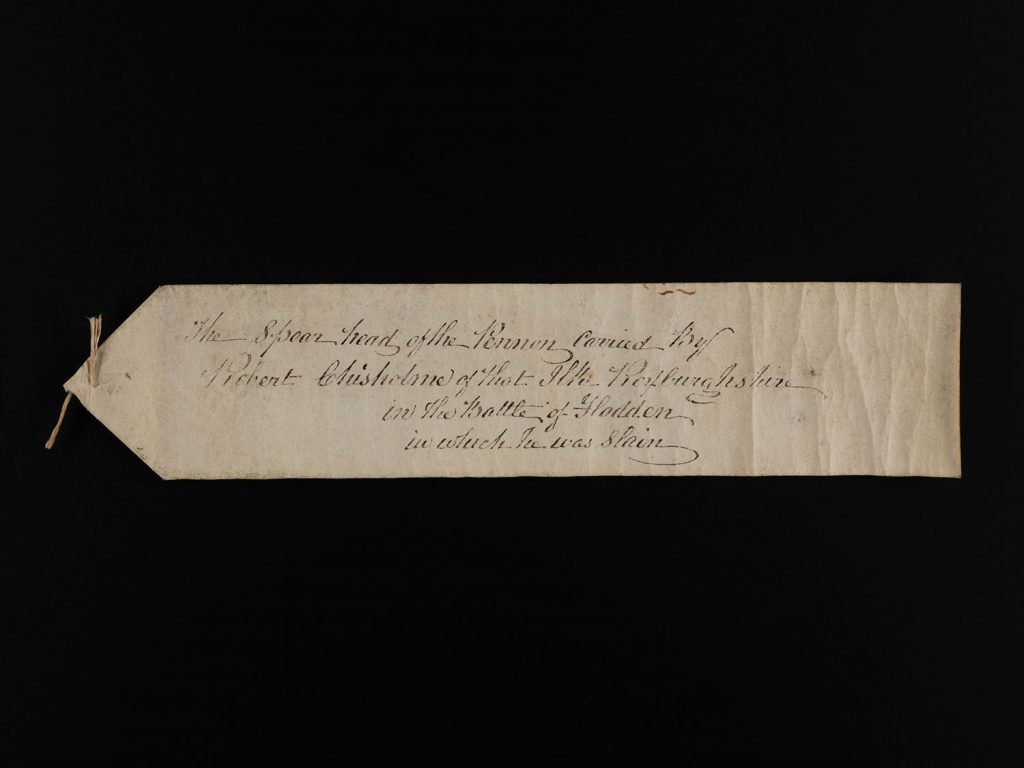

However, this particular spearhead has a remarkable story to tell. Professor Thomas bought it from an auction house in Sussex. Hidden inside the socket, he discovered a handwritten paper label, which reads:

“The spearhead of the Pennon carried by Robert Chisholme of that Ilk Roxburghshire in the Battle of Flodden in which he was slain”.

There are several things to unpick with this label. Let’s start with the easy stuff.

Firstly, the Battle of Flodden was fought near Branxton in Northumberland on 9 September AD1513, some three thousand years after the spearhead was made.

Secondly, the label refers to a specific clan: the ‘Chisholmes of that Ilk’ from Roxburghshire. Later known as the Chisholmes of the Stirches, they are well-documented in clan histories. It seems this spearhead belonged to that family at some point and was claimed to be part of the clan standard (or ‘Pennon’) that was carried into battle.

But if Robert Chisholme was slain, how was the spearhead recovered? More sceptical readers may even be asking: is this label true or just a figment of someone’s imagination? This is where some good old-fashioned research helps us understand the picture a bit better.

With some help from the National Library of Scotland, we can establish that the label was probably written some time in the 18th or 19th century. It’s clear that the label was not written at the time of the Battle of Flodden – it was added much later on. So we now have a 3500-year-old spearhead, carried into a 500-year-old battle and a 200-year-old label stuck inside the socket.

This points towards a fanciful story attached to the spearhead during the 18th or 19th century – an era where myths and legends surrounding objects are rife.

Still, it’s worth finding out whether there may be any truth in the label, and when we delve into the clan history of the Chisholmes, we are not disappointed. In 1902, the historian J.J. Vernon wrote a history of the Chisholmes of that Ilk and of the Stirches. This was published in the Hawick Express, following the death of the last male in the family lineage – John James Scott-Chisholme. In his account, Vernon says:

“ Robert and John Chisholme, accompanied their overlord, Sir William Douglas of Drumlanrig, to Flodden Field in 1513. Robert, the eldest son, died with Drumlanrig fighting beside the king, but John, the second son, survived and brought back the family pennon, the lance-head of which is still in the possession of the present representatives of the family.”

Here, then, we have an explanation for how the spearhead supposedly came back from the Battle of Flodden! It also suggests the Chisholmes did fight in the Battle of Flodden. It seems that by 1902 the Chisholme family owned a spearhead, possibly even the one now in the National Museum, with the tale attached that it was carried into the Battle of Flodden. Whether true or not, it was clearly considered part of the family history.

This begs the question: how did the spearhead end up in an auction house in Sussex? Again, family history can help us with this mystery, and work by Dr Margaret Collin has been especially informative. By 1902, only three members of the Chisholmes of that Ilk and of the Stirches are known to have been living, all female relatives of John James Scott-Chisholme. Two of these three women are recorded by the national census to have lived in Sussex in 1881 and 1901. If this important family heirloom was in the possession of one of them, it may well have ended up in the care of an auction house, perhaps following their deaths. It may be that the label was written and inserted into the spearhead around this time, as the family lineage was in decline, to preserve some aspect of the family history. True or not, it was important that the mythology surrounding the spearhead lived on.

There’s one final thing to consider. Where did the spearhead come from? We will never know, but we can speculate. We know that the Chisholmes owned lands in Roxburghshire so it’s most likely that the spearhead was found on the family estates at some point. The form of the spearhead is in keeping with other discoveries of Bronze Age objects from this area.

We also know that beliefs, magical properties, and special histories were often attached to objects found by chance. Bronze Age amber beads found on the Glencoe estatewere believed to cure blindness. In Kincardine, Inverness-shire, a hoard of Bronze Age weapons found under a boulder includes an axehead said to have been attached to Colonel John Stewart’s flagstaff and carried into the Battle of Culloden. The Chisholme spearhead could be a similar type of object.

Let’s sum up what we know. It seems that by the late 18th/early 19th century the spearhead was a Chisholme family possession, perhaps found on their lands. At some point, someone who knew the Chisholme family history wrote a label, recording the story that this spearhead was carried into the Battle of Flodden. It seems likely the spearhead was a treasured family possession, perhaps passed down as an heirloom, until sadly the last of the lineage died and it ended up at an auction house.

It would be easy to dismiss this associated story as fiction, but this misses the point. This spearhead allows us to think about the connections between people and objects, and challenges us to wonder about what makes objects special. Is it the age of an object? Or is it the stories that cling to them? Using the Chisholme spearhead, we can connect with the mythologies of a 19th century family with a proud border history in a way we can rarely hope to achieve. Was this just a story? Or was an ancient object indeed carried into a medieval battle?

This blog post draws on research conducted with Trevor Cowie due to be published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 148, later this year. I am grateful to Margaret Collin for allowing access to her ongoing research into the Border Chisholmes.