“An exhibition of samplers reveals personal perspectives on Scotland’s social history”, says Helen Wyld, Senior Curator of Historic Textiles.

Samplers are pieces of needlework that were made by girls, and occasionally boys, as part of their education. They have been made anywhere needlework is practised (the word ‘sampler’ comes from the Latin exemplum, meaning ‘example’), including Scotland.

The new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, Embroidered Stories: Scottish Samplers, showcases and celebrates American Leslie Durst’s collection of more than 550 Scottish samplers. We believe hers to be the largest collection of Scottish samplers in the world (at present National Museums Scotland has about 200 in its collection).

Samplers usually include the names of the girls who made them, and Scottish samplers in particular often show the initials of extended family members. These details have enabled Leslie to identify the girls through church and census records and to conduct in-depth research into their lives. This makes her collection a unique archive of Scottish social history from the early 18th to the mid-19th century and a valuable glimpse into the lives of ordinary families.

By the 18th century, samplers were intended to demonstrate a girl’s education through the inclusion of alphabets, multiplication tables and religious verses, but they can also reveal other details of their makers’ lives.

References to towns, buildings and events are more common in Scottish samplers than those from England and Europe, giving a sense of what was important to the young girls stitching these pictures.

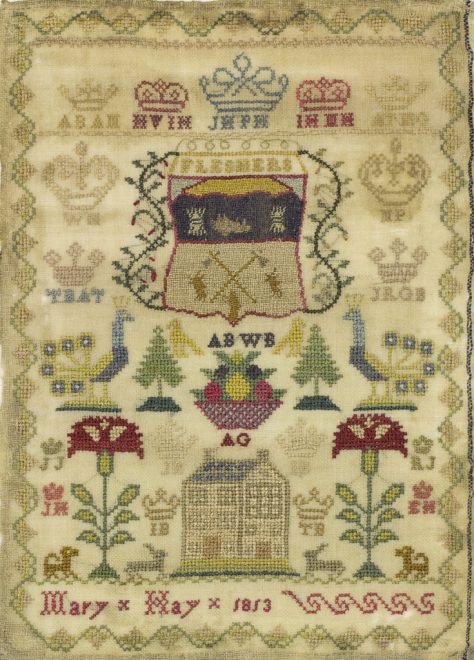

We find the arms of the Flesher’s company in the sampler of Mary Hay, daughter of an Edinburgh flesher (butcher), while the now-ruined Dalquharran Castle in South Ayrshire appears in a sampler by Margaret Eiston. Leslie’s research has revealed that Margaret’s father was a mason in Ayr and may have worked for the castle’s designer, Robert Adam.

Scottish samplers also chart social change and the spread of education. Interestingly, relatively few are made by aristocratic girls – most come from the middling ranks of society.

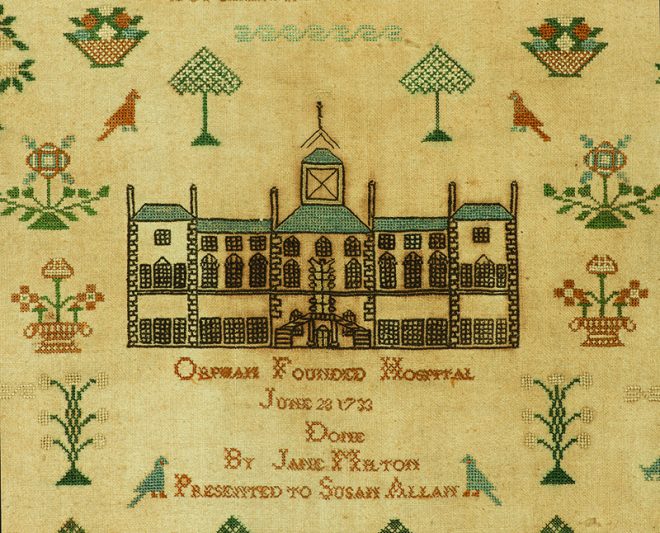

As education became more universal, less privileged children made samplers. Jane Milton sewed hers while growing up in the Orphan Hospital of Edinburgh – in such institutions sewing was seen as a useful skill to equip girls with a means to earn a living.

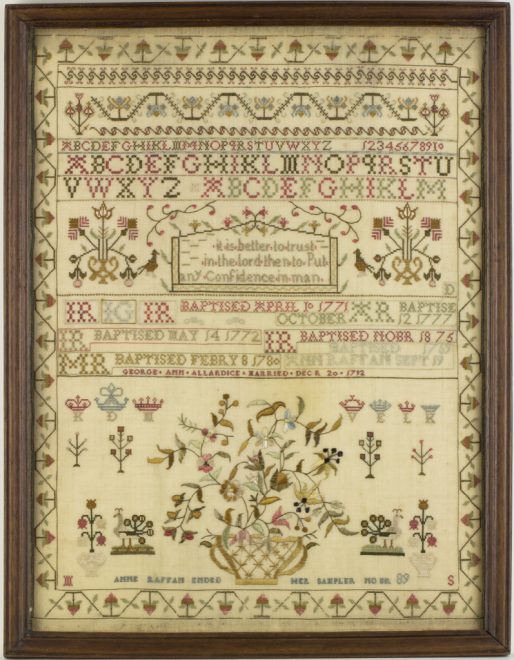

The personal stories are perhaps the most touching. A sampler marked the attainment of skills and social graces, and sometimes recorded further milestones. Anne Raffan’s sampler of 1789 shows her siblings’ baptism dates and, in 1792, aged 23, she added the date of her own marriage.

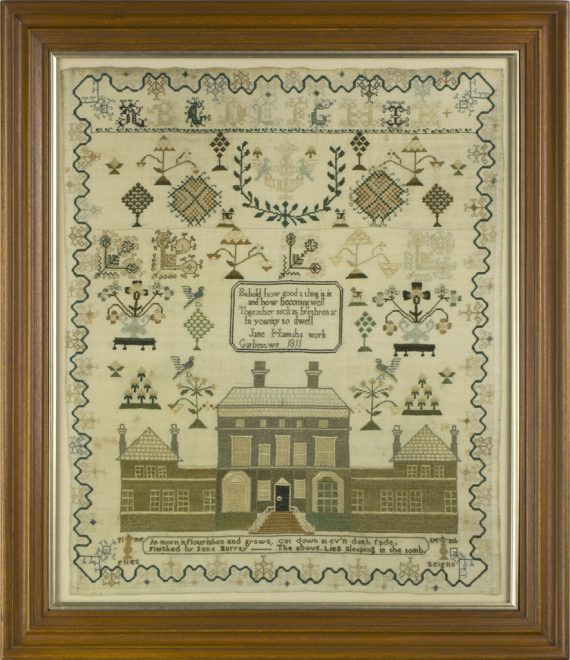

A sampler begun by Jane Hannah of Garlieston has this touching addition by her friend: “the above lies sleeping in her grave; finished by Jane Murray”, and below the words “Time Flies; Death Reigns”.

Made by hand during their formative years, samplers record the things most dear to their young makers, and often these are the only records of lives that would otherwise be forgotten.

Get an insight into the lives of children in the 18th and 19th centuries through this unique collection of Scottish samplers on loan from American collector Leslie B. Durst.

Embroidered Stories: Scottish Samplers is on at the National Museum of Scotland until 21 April 2019.