I am a PhD student in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh. For several years, I have been studying the bones of small mammals (mice, voles and shrews) that have been collected during archaeological digs in Orkney, and are now kept in the Vertebrate Biology collections at the National Museums Collection Centre.

When talking about mammals, our first thought is usually of domesticated animals like dogs and horses, menacing predators like lions and tigers, or the biggest animals on earth, elephants and whales. However, most people are usually surprised when told that all of these big beasts comprise just a tiny minority of the mammals, most of which are small enough to fit into the palm of your hand. They are not only numerous but also highly diverse, from the red-toothed shrews with their periodically shrinking heads, to the toothless rats of Indonesia and the carnivorous grasshopper mice from North America, with their tendency to howl at the moon. However, my first interest was not in the fascinating biology of these “micromammals”, but rather more to do with archaeology and their interaction with people in the past.

My Masters dissertation was on rodent bones from the world famous Neolithic (stone age) dwellings at Skara Brae in Orkney. The Orkney archipelago is an especially interesting place to study micromammals, because it was cut off from the Scottish mainland by rising sea levels at the end of the last Ice Age, and all of these animals must have been introduced later, most likely by people. Some of the larger animals were probably introduced deliberately, for example rabbits (as food) and foxes (either for fur or to control the size of the rabbit population). However, more intriguing is the Orkney vole, a form of the Eurasian common vole, which is not encountered anywhere else in the British Isles, and was probably introduced from somewhere in western Europe. Many species of mammal are well adapted to living comfortably within the proximity of humans and, more specifically, their stored food. Some, such as house mice and black rats, were inadvertently transported all around the world by people. However, rodents may not always have been stowaways on ships.

I found out that the vole remains were concentrated within the refuse at Skara Brae, so they might have accumulated as a result of pest control. However, some of the bones had been burnt in a way which suggested roasting over a fire, which is more suggestive of food processing. Tiny mammals, like their bigger brethren, can be eaten. Guinea pigs are a good example of a species that is kept and bred for food, considered a delicacy and even a cultural symbol of identity for people who live in the Andean mountains of South America. The results of my study were published in Royal Society Open Science. There was a lot of interest in the story from around the world and even some BBC coverage, because there was no previous evidence of people eating rodents in this part of the world.

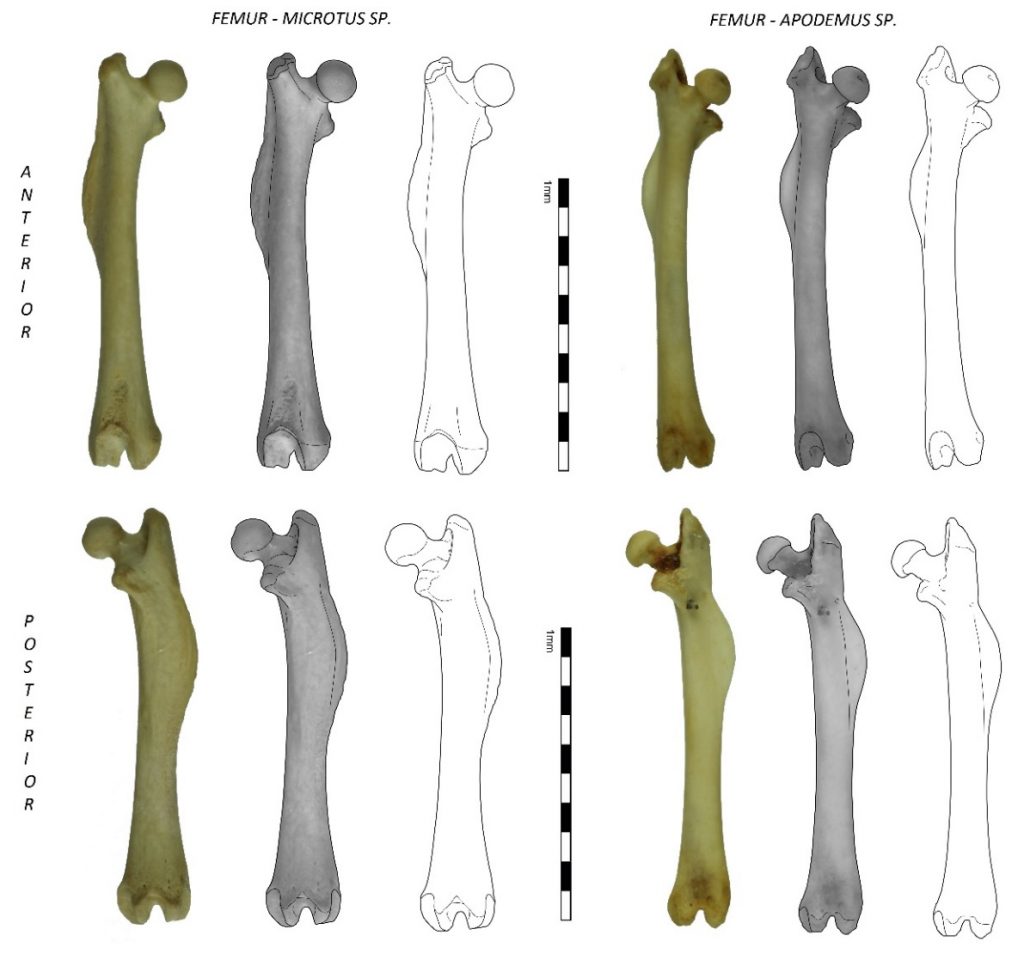

Now I am working on a bigger project, finding out more about the small mammals in these Orcadian archaeological sites and their relationship with the people who lived there. I am looking at samples of micromammals from different locations and time periods. There is a wealth of information awaiting those interested in conducting research on micromammal remains, but such work is definitely not easy. Small animals leave tiny, and often brittle, bones which are harder to find and retrieve than those of bigger mammals. Moreover, the sheer number of species, with different proportions and sizes, makes their identification difficult, even for experienced researchers.

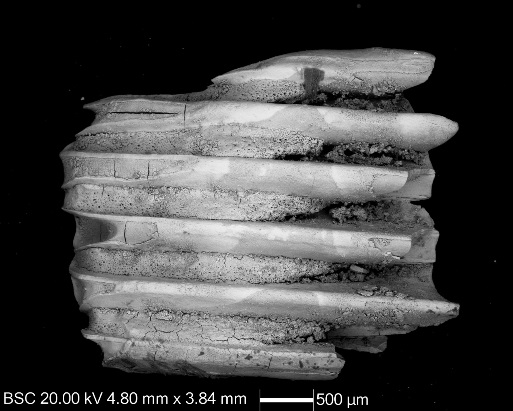

I am now using more high-tech methods, such as a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), to examine the rodent remains in more detail and look for microscopic marks that are left by digestion. For this part of the project, I am working with Dr Lore Troalen, Analytical Scientist at National Museums Scotland.

I hope that my work on the microenvironment of Orkney may help to establish a more reliable methodology for further studies of micromammals in the more complex environments of Eurasia, Africa and the Americas.