A degree work placement provided the perfect excuse to delve into National Museum Scotland’s rare book collections, and discover all the unusual and exciting things on offer.

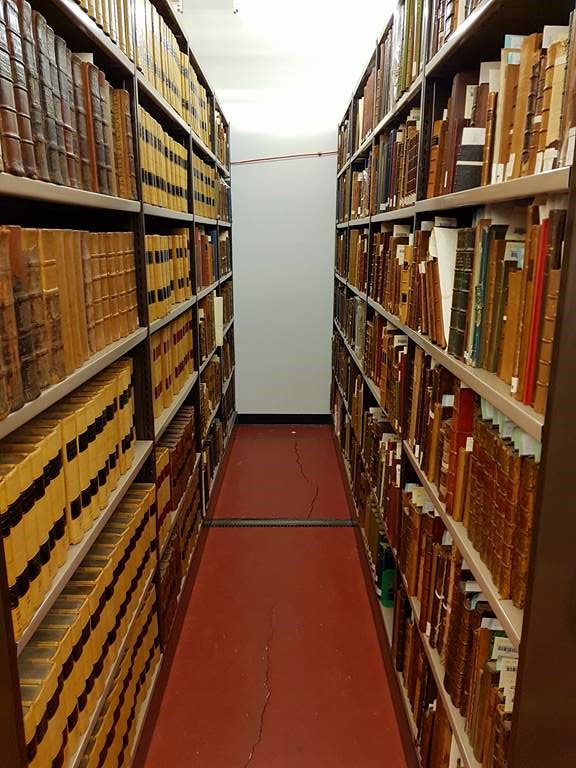

As a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh studying for an MSc in Book History and Material Culture, the work placement had to be one of the most highly anticipated elements of the course. The opportunity to enter the hallowed realms of one of Edinburgh’s cultural institutions, to go behind the scenes and even, hopefully, contribute to their work in some way was the primary reason for me choosing this degree program. Having had glimpses into the safes and storerooms of the Research Library at the National Museum of Scotland whilst volunteering over the summer, I was thrilled to be asked to continue there for my work placement.

My challenge was thus: to expand and enhance the catalogue records for the pre-1700 books in the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland collection. ‘The Society was founded in 1780, with the aim of promoting the material cultural history of Scotland, and its extensive collection forms the foundation of the National Museums Scotland library collection today.

The actual cataloguing work involved grappling with online databases and some basic coding, the theory of which I’d so far only heard in class, so I revelled in the opportunity to get some hands-on practical experience and learn this technical literacy. Examining each volume carefully, and supplementing my knowledge with that of online catalogues, I added as much information as I could into the library catalogue, including full titles, publication details, donor history and so on. Stumbling blocks included books entirely in Hebrew, European languages or, most commonly, Latin (why, oh why did I not study Latin in school?!) and deciphering the bewildering handwriting of original owners.

Despite these difficulties, I managed to identify and expand the records for every item on my original list, and more beyond that! The books covered a wide breadth of subjects, including:

- Covenanter’s tracts and pamphlets.

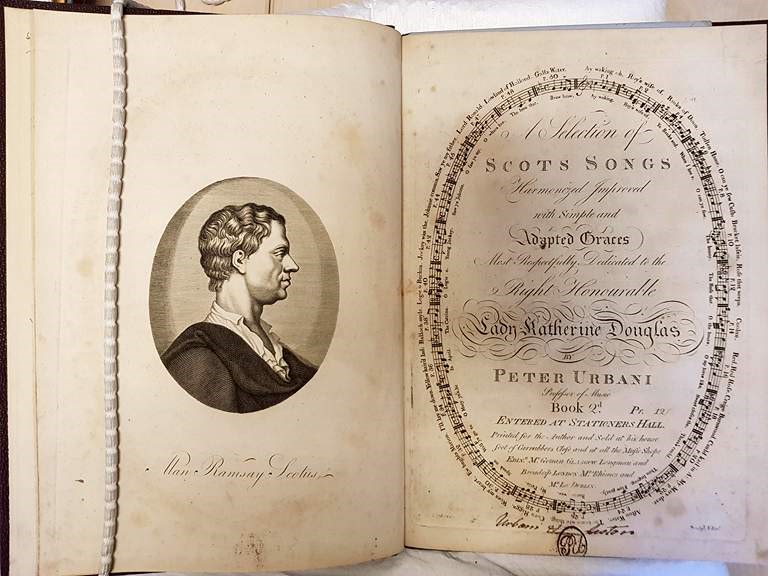

- A selection of sheet music for songs in Scots.

- Francis Bacon’s musings on life and death.

- A 17th-century Dutch to English dictionary.

- A Hebrew Bible.

- Technical books on husbandry and farming practices.

- A collection of maps of the Netherlands.

Particular favourites included a huge leather tome with a gold tooled border, titled Suecia antiqua et hodierna, or Sweden ancient and modern, and opening to reveal beautiful etchings of maps and views in Sweden. The title page contained minimal publication information about the volume, frustratingly for a cataloguer, but was so beautifully decorated that I couldn’t mind.

This rich mythological scene shows Perseus, triumphant in his decapitation of the Gorgon Medusa, handing a laurel crown to a seated and smiling goddess whilst Poseidon looks up from below.

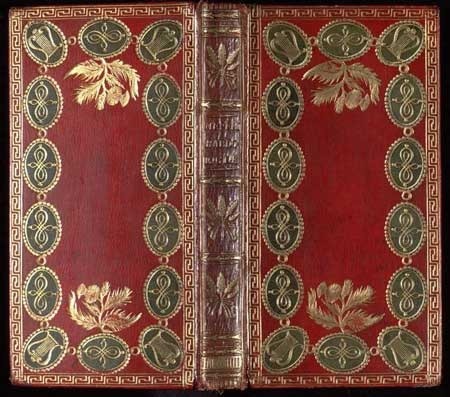

Another favourite was a tiny 1617 volume on arithmetic, Rabdologiae libri duo, by Scottish mathematician and physicist John Napier. I was drawn to the volume less by the complex contents of the text than by the beauty of its binding. The boards were a bright eyecatching red, with a pattern of green ovals and gold tooled flowers and borders. A label on the inside cover identified the binders as ‘Scott Edin.b’, whilst a little extra digging named them as James and William Scott.

A rummage amongst the library shelves found a book by J. H. Loudon dedicated to the history of these two men, with full page pictures of their work. I quickly found my volume, described as crimson morocco binding with peacock blue endpapers, and then flipped back to the introduction to gain some context.[1] I learned that James Scott was appointed as the official bookbinder to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1781, just a year after its foundation, after gifting them a beautifully bound copy of the Foulis 1770 edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost. A reproduced letter, written by Scott to the Society in August 1781, revealed his ambition to be at the height of his craft; ‘To be at the head of my Profession as a Tradesman, has been and still Shall be the Study of my Life.’ He continues:

Many of my brother Tradesmen may boast of much more riches than I ever expect to be possesed of, for my share, I envy them not, much good may it do them, and you may believe me, Dear Sir; when I assure you that the Aprobation of a Society; formed on the most Liberal plan and Composed of Members eminent for their Taste and love to their native Country: is to me a much more valuable return than any pecuniary reward they may please to make me.[2]

Despite the insistent disinterest in money displayed in his letter, Scott must have hoped for some beneficial patronage from his association with the Society. He was disappointed however, and eventually had to abandon his practice due to financial constraints. Loudon paints James Scott as an ‘unpractical idealist’ dissatisfied with the humdrum work he must do to survive and ‘unable to compromise with the economic constraints of daily life.’[3] However, his dedication to producing beautiful volumes to the highest standard can clearly be seen in this example, and is, in my view, to be celebrated.

This project has been full of personal benefits, from honing my palaeographic skills to gaining experience in cataloguing, and to acquainting me further with the Museum’s collections, but it should hopefully have some wider profits too. Better catalogue records will make these books easier to find, and hopefully encourage more people to engage with the treasures in this library.

Inspired by my finds? You’ll find the Research Library on Level 3 of the National Museum of Scotland. It is open to visitors during museum opening times (from Monday to Friday, 10:00 to 17:00), and there are 12 study spaces and comfy seating. You can browse the collection here.