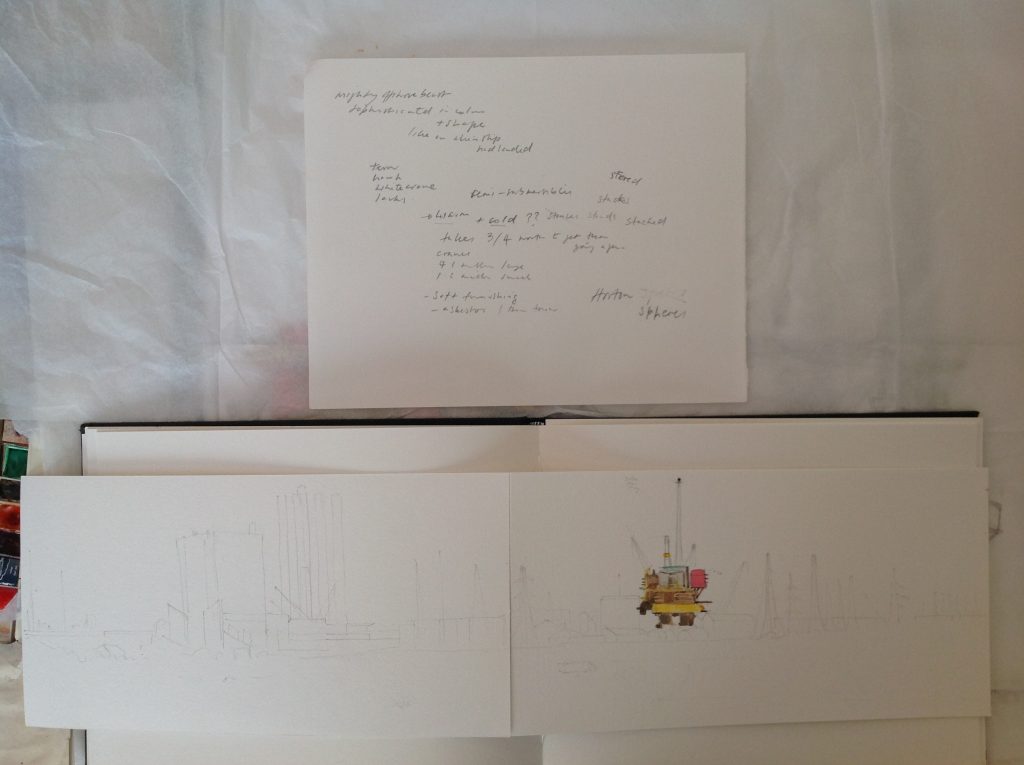

Extracts from artist’s diary from Brent Delta Platform: June 2016

The Brent Field was one of the most lucrative oil discoveries in the North Sea. For forty years its four platforms, Alpha, Bravo, Charlie and Delta produced over three billion barrels of sweet light crude oil. This oil, evolved and formed from the Jurassic period, was considered the crème de la crème of oils, the equivalent of the perfect malt and a distiller’s dream, Brent Blend. By perfect happenstance, Shell initially named all its UK oil fields after water birds in alphabetical order by discovery: Brent refers to the Brent goose, the golden-black goose.

Thousands of people worked on these platforms throughout the field’s forty years of production. They hold so many memories. For the general public, however, perhaps they have vague recollections of the Greenpeace Brent Spar occupation campaign in 1995, two tragic helicopter incidents, in 1986 and 1990, or the regular radio/TV global reportage of the Brent crude oil price.

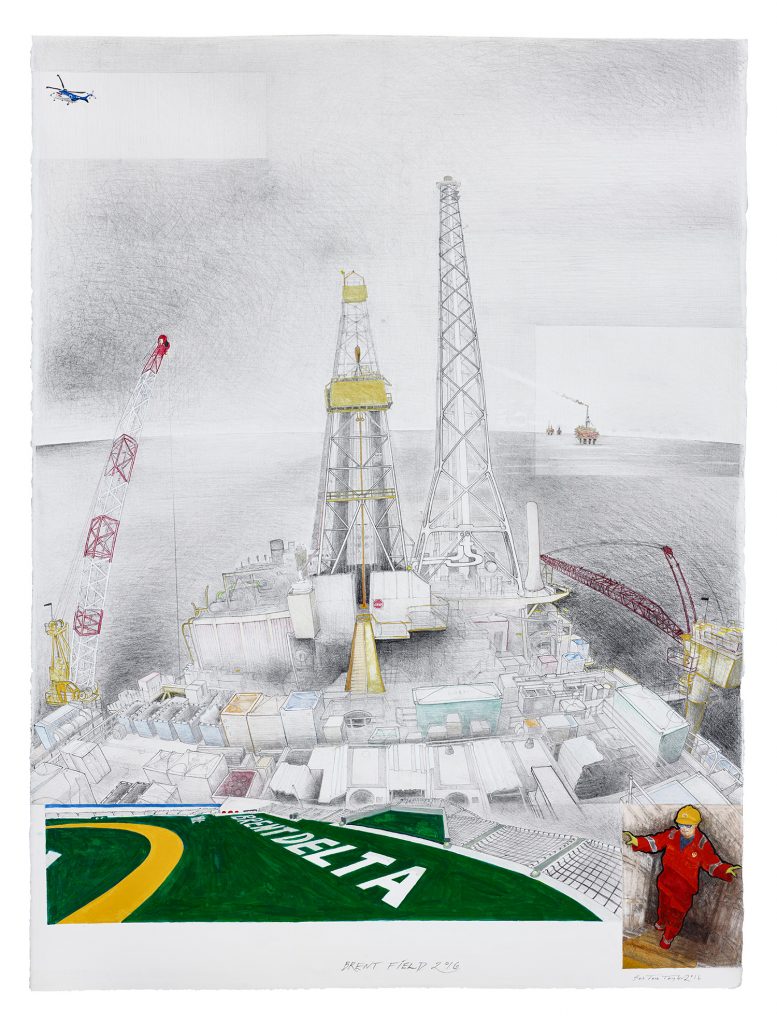

In June 2016, I was given permission to visit Brent Field by Shell UK. Brent Delta was weeks away from final abandonment and personnel evacuation. This platform was very different to any other I had been on. Apart from Alpha, all three Brent platforms had vertical flare towers and three giant subsea concrete legs supporting their topsides. Surrounding the base of these legs, sitting on the seabed, were massive reinforced concrete tanks, subsea storage cells that were once used to store and separate crude oil before export. Bravo and Delta each had 16 reinforced concrete tanks which still contained layers of crude oil, called attic oil.

Whilst on board I was given an in-depth tour by George Stewart, OIM (offshore installation manager). He explained that for nearly six years they had been busy decommissioning this platform and reinforcing certain module wall areas with thick welded steel in preparation for the forthcoming giant lift in 2017 by the world’s largest construction vessel, Pioneering Spirit.

In February 2015, I was lucky enough to get a ticket to Pioneering Spirit’s inauguration. The vessel was anchored at sea off Rotterdam’s massive docks. It was a weekend of sheer exuberance and celebration for this three-billion-dollar maritime giant: Hollywood glitz meets Dutch style staged between the ship’s giant bows. Onboard guests lined up to be greeted by ship owner Edward Heerema and his wife who masterminded the event. Amongst the glamour of high heels and designer clothes, opera singers, installation artists, performers and actors all mingled together. It was cultural ‘eye-candy’ everywhere you looked in the setting of an offshore industrial battleship.

On Delta looking south, I had a clear view of Brent’s three other platforms: Charlie’s gas flare still alight and burning; Brent Field’s last lonely flag flying at half-mast. It was remarkable to see these platforms all lined up: the scale and complexity of it all with its massive subsea structures and pipelines, all hidden below the sea’s surface. It must have been an extraordinary sight during the field’s height of production with all four platforms’ flares and a separate external flare tower going full-bore.

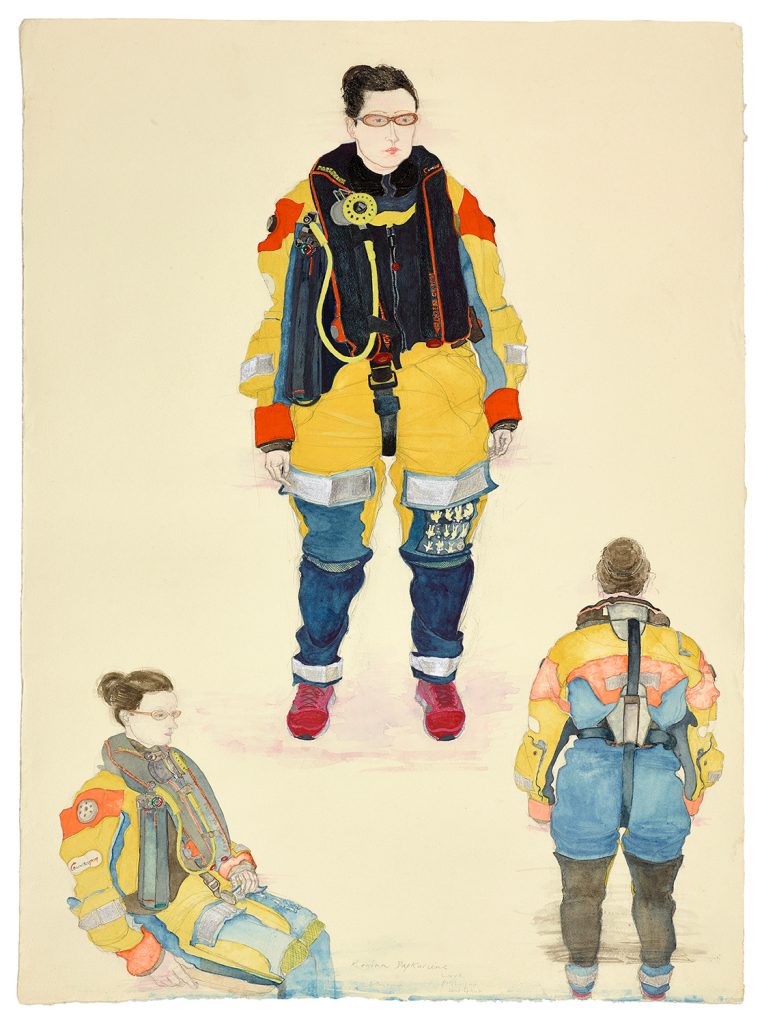

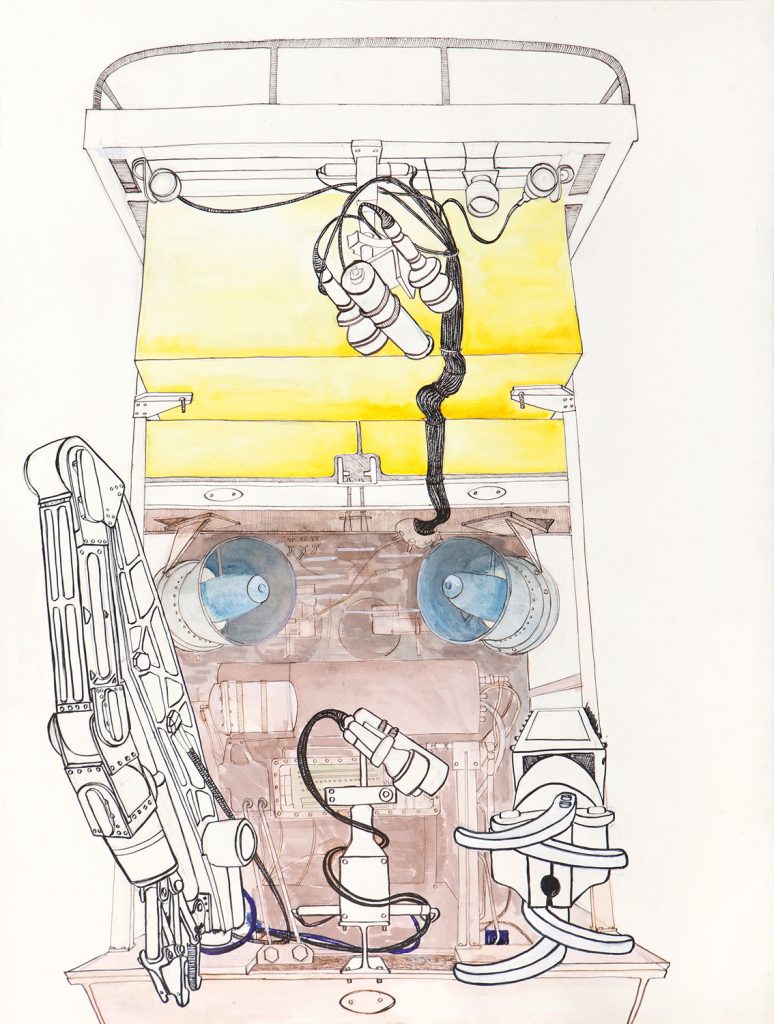

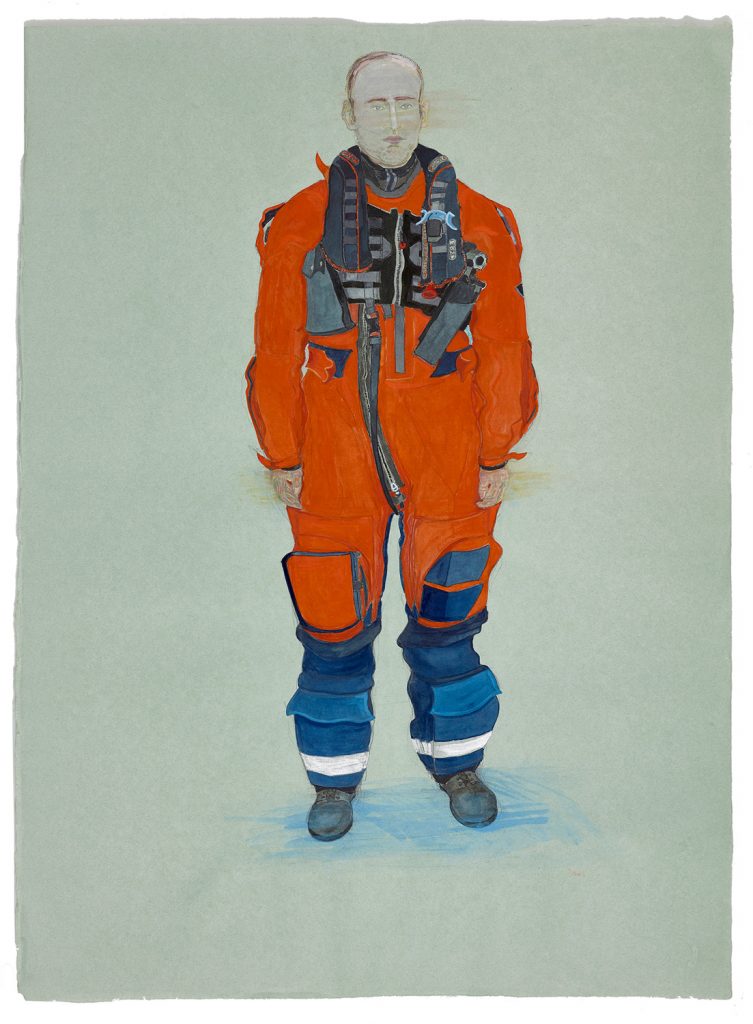

I visited the Remote Operating Underwater Vehicle (ROV) operations office, which was in a container outside on the deck. I was met by Marcus, in charge of ROV operations. Beside him were his two ROV operators busy working at their controls and staring at big live-action screens showing film footage direct from the ROV’s camera lens which was operating far below near the subsea leg storage cells areas. We identified different fish swimming around on screen; it was all a bit surreal and hi-tech. Shell had been working with NASA to develop a technique to access the cells to gain images of their content. NASA had designed ‘sonar spheres’, bowling-ball-sized satellites, to access the cells through existing pipework. I was given a NASA cloth badge as a souvenir.

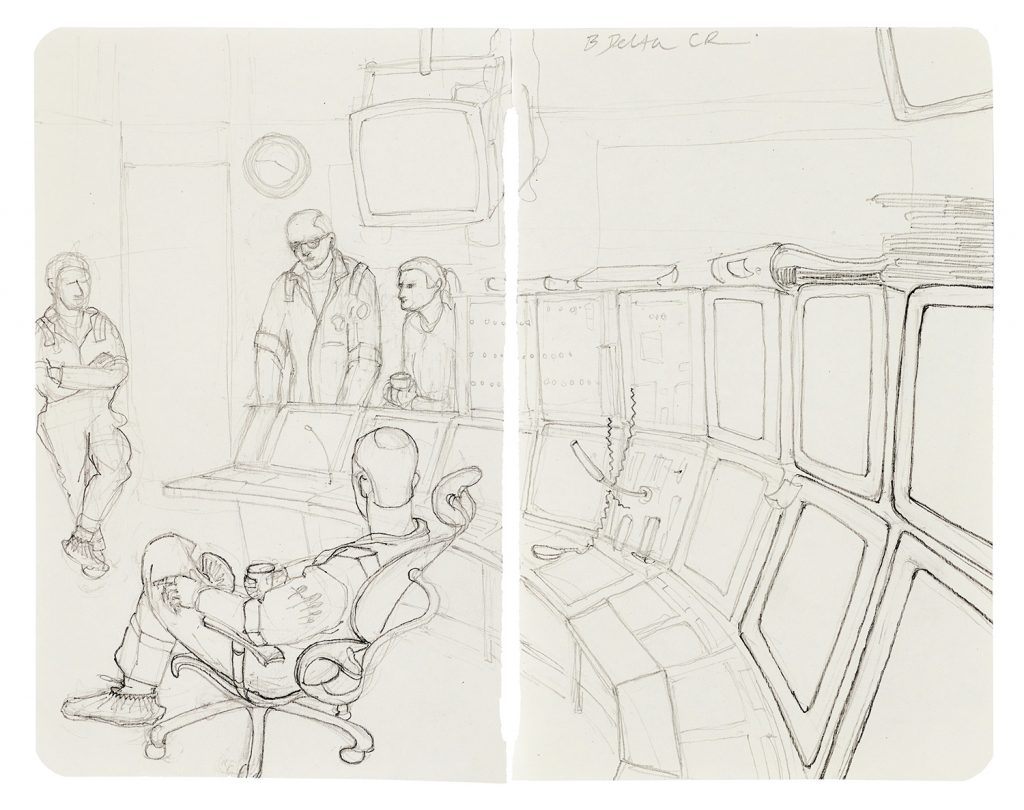

On my last day during tea-break, nib-nabs as it is known, the control room operators talked about the decommissioning and the proposed topside lift by Pioneering Spirit. They were in awe of this proposed lift and would have loved to have been part of it. Always on the lookout for personal human touches, I was taken by one of their inventions: a beautifully made teacup-carrying device made out of brass pipe-ring fittings, fanned out in the shape of a flower; it could hold six plastic cups at a time without fear of spillage.

Able UK Seaton Park Yard, Durham County

In April 2017, Brent Delta’s 24,200-tonne topside was lifted by the Pioneering Spirit from the Brent Field in the northern North Sea. This marked the world’s heaviest offshore lift, which just took over 10 seconds. It was transported to Able UK Seaton Park yard in Hartlepool where it is being fully dismantled over a 12-18 month period; 97% of the Brent Delta platform material will be recycled.

This was the first time in UK waters that a complete platform topside this scale was brought to shore.

Extracts from artist’s diary June 2017

Shell UK granted me permission to visit Able UK yard during their Brent Delta’s Final Farewell week’s events.

The road to the yard ran in parallel with the long stretch of Seaton Carew beach front and as we came round the corner from the long coastal road stretch, it hit you with a bang: Brent Delta topside, now docked on land with its flare tower soaring up to the sky, extinguished and no longer burning off years of unwanted oil well gases. An alien beached beast of gigantic proportions had reached its final resting place. It stood out from an industrial horizon; to its left a nuclear power station with huge pylons and wires branching out burdened with carrying national grid electricity, hot and cold stacked jack-up rigs, and to its right, massive oil storage tanks.

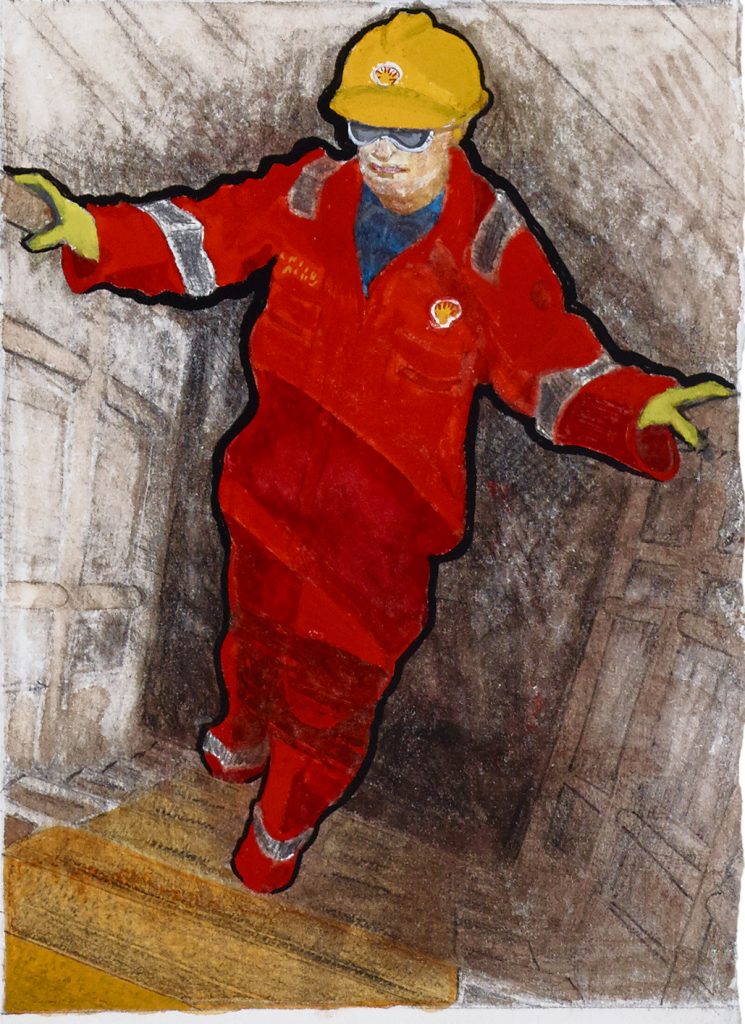

In the yard a marquee, minute in scale, was sited close to Brent Delta. I met up with Shell’s decommissioning team who had set up camp in Able UK’s portacabin offices nearby. Inside everyone was tapping away on their laptops in preparation for the week’s schedule ahead. I got into my on-site safety clothing kit and then got a lift down to the marquee where the catering staff and the presentation team were all buzzing around. Displays and TV screens were being set up for illustrating Brent Field’s 40 years production-life timeline. Platform artefacts were being laid out on tables; including the much-coveted tea flower.

In the heat of the day, outside the marquee and away from all the bustle of activity inside, I chose a drawing spot in the shade looking straight up at Brent Delta. The only other people who would have viewed this angle in its operational offshore lifetime would have been the platform’s RATs (rope access technicians), scaffolders and cargo supply vessel seafarers. This ‘ark oil’ now had stumped elephant feet, amputated from its three massive concrete legs, which had been left behind in the northern North Sea. This would have been a dream stage set for any sci-fi movie director, no CGI would be required for effects or scale, it was all here.

My hotel bedroom looked out onto the Royal Navy museum which had several vintage vessels nestled in dock including the UK’s oldest warship HMS Trincomalee. This whole area is steeped in industrial maritime history and I could see it was desperately trying to find another identity amongst the recent wastelands of supermarkets and retail parks. Young people, every evening after the heat of the day, swam and larked around in the murky quay waters.

I also drew Brent Delta from the outside of its graveyard perimeter. In the early morning, I walked from my hotel to Teesmouth National Nature Reserve, a small patch of undulating sand dunes leading to the sandy shore estuary, the mouth of the river Tees. On a dune hillock perch-top, I set up my art camp to draw the incongruous site before me. There were birds singing all around me, oblivious to the constant flow of dog walkers, cyclists and runners who were following the reserve’s path networks below me. Skylarks were hovering high above; artic terns, with their dagger-like wings, were swooping back and forth along the shoreline behind me. A hawk even rested for a while on a rock close by, busily pruning itself. It was a complexity of nature’s fragility mixed in with human’s industrial invasion.

Within this small area of Hartlepool, Middlesbrough and Redcar were concentrated our nation’s old and contemporary industries. It read like a visual textbook; an offshore wind farm out at sea, a constant flow of maritime freight vessels, abandoned and redundant Redcar steelworks. Brent Delta stood out amongst these muted grey tones, although its own painted colours were now faded; changed to shades of delicate pinks and rusted yellow ochres after its 40-year battering from its maritime habitat.

For the week’s farewell event, every day Shell UK organised different parties of invited guests to the site: VIPs, school children, bereaved families who had lost a relative on the platform, and the local community. I was asked to be present for the Shell pensioners, ex-employees and contractors day; people who had worked on Delta from its birth right up to its death in 2016.

The hot weather had been building all week. That morning a thunder and lightning storm hit, so the marquee was being heavily tested by torrential rain. Amongst the first guests to arrive was George Stewart, now happily retired. As we looked out at the platform he observed that, as OIM, he had said goodbye to Delta three times. On his last visit, he left his kit onboard as he thought that he would be returning; he was amused to see his coveralls and hat were on display, he was still after his boots though! He remembered how intense the period leading up to the lift had been.

As everyone congregated, speeches were made by the Brent decommissioning team and the guests were shown a specially commissioned corporate film. The exciting part for everyone was a tour onto Delta and they got kitted out into safety boots, hard hats and high-viz jackets from the makeshift stores inside the marquee. A site safety video was shown before they ventured out on site; as the groups stood under Delta they looked like stick insects by its enormous elephant feet. An eight-storey scaffolding stairway was constructed for people to get up onto the topside. One lady returned to the marquee saying she had vertigo going up the stairs. St John’s Ambulance officers were on standby.

When people returned I could see it was very emotional for some of the pensioners, who had not been on Delta since they had retired many years ago. I briefly saw George saying he could not find his boots in his old office and that it was very unsettling for him to go back in there by torchlight in the darkness. He quietly left the marquee without anyone noticing.

After the day’s event, I was given the chance to go up to Delta. One of the guides escorted me and gave me a tour. From the ground looking up at its torso’s underbelly, he pointed out a bent metal section, the result of ‘the 100-year wave’, which hit Delta. I could see the massive metal bar frame support system up close. This held up and supported the weight of the topside welding reinforcements above.

Climbing the scaffolding stairway up onto the platform was a very strange and odd sensation. On my previous visit, almost exactly a year ago, I arrived by chopper far out at sea. It was all a bit unsettling walking around and climbing up and down the different levels; looking into where once the wellheads and Christmas trees were located, now empty spaces, ghost-like. All exterior module doors were welded up in preparation for the lift and sailing. It was even weirder entering the living quarters by torchlight, all areas in total darkness. The control room was just as it was left before final abandonment. As I remembered, work folders were all lined up above the monitor screens and old photos still on the walls. Outside on deck was the estuary, bay, jack-up rigs, an oil refinery and the gentle hill slopes of Durham County in the distance. It did not seem real.

The next day I got the chance to view and draw Delta from different quayside angles within the vast yard. A nice Irish guy from Able UK drove me around the site. He was quite happy to sit in his car whilst I drew and took photos. He was busy negotiating and searching to buy a bigger crane for the Delta breakup. Their £4.1 million new crane on site was not big enough. He explained to me Delta’s dismantling schedule. The asbestos lining had to be removed and taken to a landfill site for burial just across the road from the yard. The soft furnishing would be removed next. The highest points, the towers, would be toppled to the ground, which would be layered with sand to buffet their impact. He estimated that fifty men would be working on this project. It was also interesting to learn that the minute Delta landed onto Able UK’s site it was no longer in Shell’s ownership. It was quoted that Shell UK was paying £40,000 per day for their week’s events.

On my final site visit, I drew Delta from the roadside by the yard’s main entrance. It was very busy and unhealthy with the stench and wafts of fumes from the traffic, landfill site nearby and oil refinery across the bay; a toxic mixture to my nasal senses. I could not stay there for too long and I walked back to my favourite vista on the nature reserve before bidding my own final farewell to Delta.

The Age of Oil exhibition was on display at the National Museum of Scotland from 21 July to 5 November 2017.

An Age of Oil publication featuring Sue Jane Taylor’s works and diary extracts is available to buy here.