A chief of police, ten princesses and a high official from a Roman-era Egyptian family are all helping Dr Margaret Maitland with her enquiries.

The Senior Curator of the Ancient Mediterranean collections at National Museums Scotland is the ‘detective’ behind a search for clues into the mysterious affair of ‘The Tomb’.

It is a story that has been buried beneath the shifting sands of Egypt for thousands of years, and one worthy of Agatha Christie, with her penchant for tales of archaeological digs, looted tombs and strange deaths on the Nile. As Margaret cracks the secrets of 1,000 years of burial in ancient Egypt, her focus is one extraordinary tomb that has been used, robbed, reused, excavated and then lost. Now, it is to be the subject of an exhibition, The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial, at the National Museum of Scotland from 31 March.

Carved into the desert cliffs opposite the city of Thebes in modern Luxor, the tomb was built in around 1290BC, reused for more than 1,000 years and sealed in the early first century AD. Unopened for almost 2,000 years, it was excavated in 1857, before its location was lost. Margaret has set out to rediscover the tomb through precious objects held in the collections of National Museums Scotland. These range from a statuedepicting a chief of police and his wife; wooden labels from the mummies of ten princesses, the daughters of Pharaoh Thutmose IV; and a gilded funerary wreath for a Roman-era Egyptian official.

The tomb was originally constructed shortly after the reign of Tutankhamun for the Chief of Police and his spouse.

“The sheer wealth at that time was staggering,” explains Margaret. “The highest officials were building these tombs, and our tomb was built for a man who would have been in charge of law and order in the capital, guarding the Valley of the Kings. We have a beautiful statue depicting him and his wife in an affectionate pose with their arms aroundeach other. Unfortunately, we don’t know his name, as it has been damaged, but we have enough to know that he was Chief of Police.

He built an immense tomb. It consists of a tunnel carved 38 metres into the rock with a burial shaft sunk six metres deep. The amount of engineering that went into this is stunning. The construction would have been extremely costly, although he did save by making use of an existing square courtyard cut into the cliff face for King Thutmose IV’s daughters.”

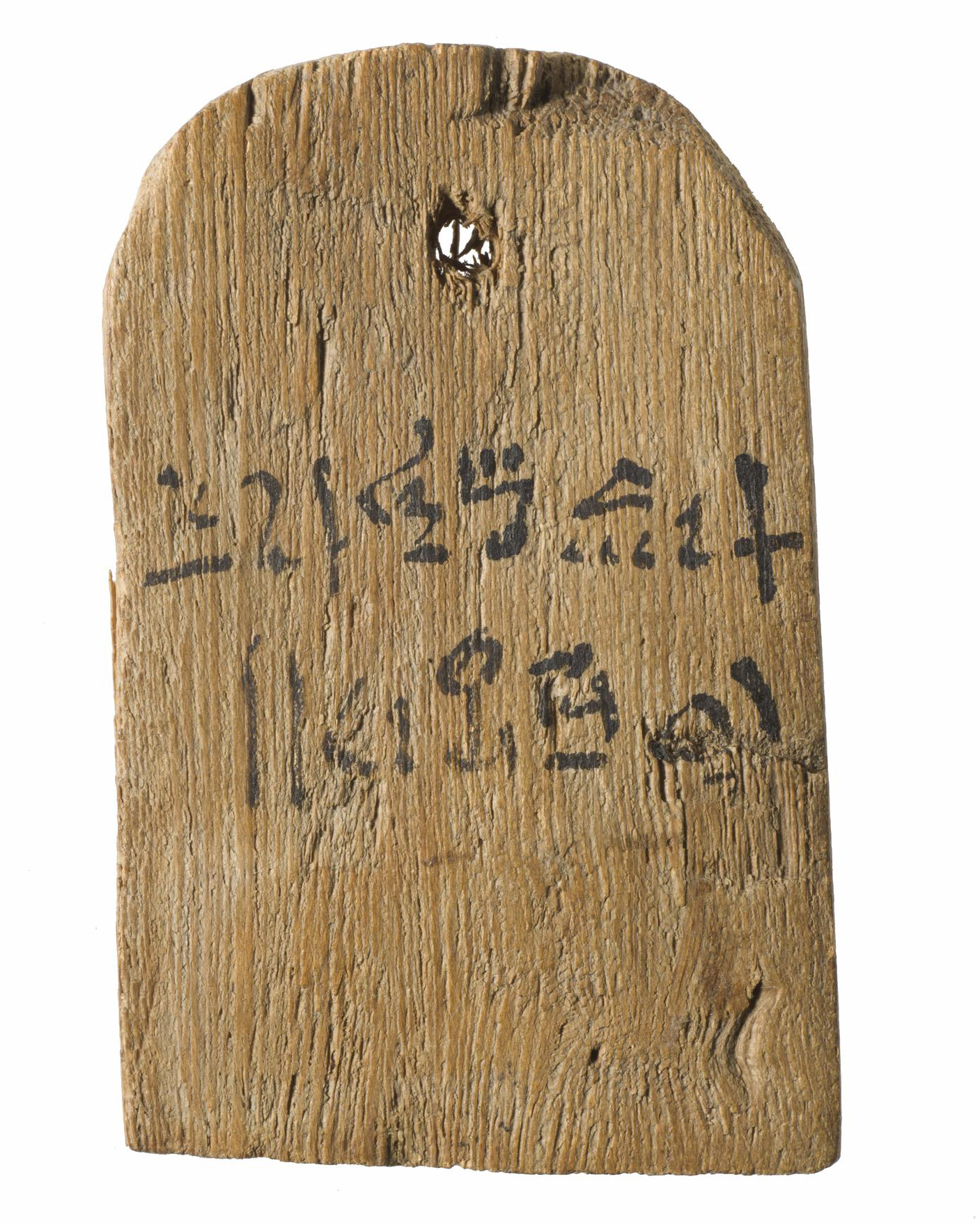

The burial of the princesses was relatively modest, hence the wooden labels, which are name tags. The Egyptians believed the preservation of the name was essential to survival in the afterlife. In contrast is an exquisite gilded ebony and ivory box of King Amenhotep II, which Margaret says was probably found in the tomb.

Margaret said: “The sheer wealth at that time was staggering. The highest officials were building these tombs”.

This beautiful work of art and its breathtaking craftsmanship hints at the extent of royal wealth and power in Egypt’s golden age.

“Fragments of this box – acquired with assistance of the Art Fund and National Museums Scotland Charitable Trust – are helping us to reinterpret its original decoration, which evokes the royal palace,” says Margaret.

“Ironically, although the Chief of Police was in charge of security for the royal tombs, his tomb did not escape looting, because the wealth diminished in Egypt after it had lost control of its empire. It no longer had the ability to make these grand tombs and fill them with objects, so tomb robbery became quite common, and tombs were reused and recycled. All we have that remains of the original tomb’s owners is the rather lovely statue of himself and his wife in their finery.”

Under a divided and occupied Egypt (c.1000–660BC), many tombs were repeatedly looted. Margaret describes the remaining contents as “a jumbled collection of beautiful objects”.

Others came in and reused the tomb, as suggested by Margaret’s research. She has studied many fragments of artefacts from the tomb, enabling her to work out how some larger funerary objects might have looked.

“We have been able to reconstruct the tomb itself because we have in our collection archival plans and notes of its excavation,” she says. “We will celebrate its 160th anniversary this year. Since the objects excavated in the tomb were among the earliest to enter the collection, any connection between some of the more fragmentary items and the tomb was lost. So I have been going through them and re-identifying their association with the tomb.

“It’s exciting to make these finds and, yes, it is just like being a detective. For instance, we have the remains of some little guardian figures that would have been attached to the lid of a coffin. Just by having those, we can tell the type of coffin that would have been in the tomb.

“We can also track significant changes in mummification practices through these objects – for example, in this period, internal organs were returned to the body rather than being kept in separate canopic jars. Several of these jars found in the tomb are dummy vessels, not hollowed out, but created for tradition’s sake alone. It’s fascinating to see all these changes in burial practices in just in one single tomb.”

The tomb was last reused around 9BC by a Roman-era Egyptian family. The high official Montsuef, his wife Tanuat – “we know that she died just a month after him, which is very touching” – his father-in-law Calisiris, their son, daughter and several other family members all lived through the reign of Cleopatra, Egypt’s last pharaoh. The family witnessed Egypt’s conquest by the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, seeing some of the final stages of pharaonic history – the beginning of the end of ancient Egypt.

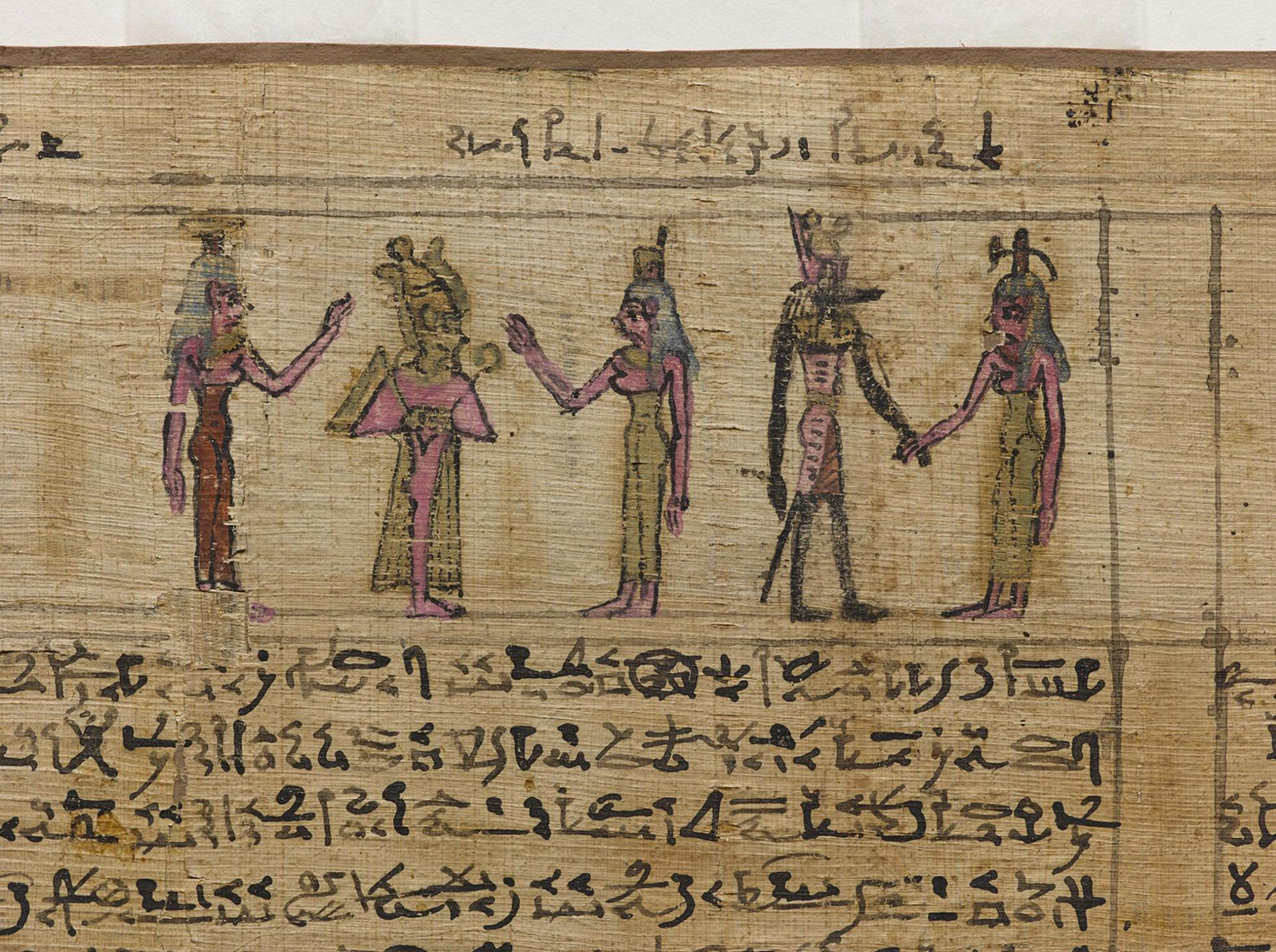

Margaret says: “The objects that relate to them show they were trying to hold on to some of the traditions, sometimes to reinvent them and make them even more ancient and magical, while bringing in classical influences from outside. We have one of their wooden coffins, a mummified young woman, a gold mask and a wreath, among other items. Their burials combine imported Hellenistic influences, such as the gilded wreath symbolising victory – over death in this case – along with revived and reinvented ancient traditions. They are reasserting their Egyptian identity in a rapidly changing world.”

She continues: “We also have the funerary papyri they were buried with. They are personalised, with birth and death dates, and little bits about their lives and how much they were admired and respected – part of the argument as to why they deserved to get into the afterlife.”

Finally, the tomb was sealed and remained unopened until its excavation in 1857. Its location was subsequently lost after a modern village grew up over it. But, as Margaret stresses, the beauty of the objects and the many finds made over the years – as well as the sheer drama of the story behind the tomb – will long inspire the imagination. “While the tomb remains surrounded by mystery, there is surely much more to discover and its story will continue,” she promises.

The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial is at the National Museum of Scotland until 3 September 2017.

Sponsored by Shepherd and Wedderburn