The Hunterston brooch is the most richly decorated early medieval brooch ever found in Scotland. Made from solid silver, the front of the brooch is covered in complex and tiny designs made from gold filigree wire, and elaborated with amber settings.

Brooches seem to have been used as indicators of status in early medieval Scotland, and surviving examples differ in their size, materials and amount of elaboration. The Hunterston brooch would have signalled its wearer as a person of significant power and wealth. But it would be wrong to see brooches only as secular power symbols. Decoration on this and other examples demonstrates that they could also carry powerful Christian iconography.

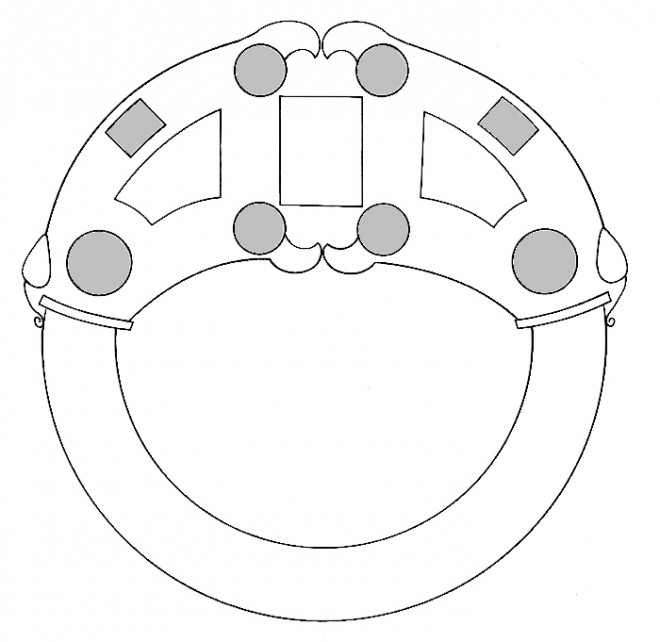

On the Hunterston brooch this imagery is hidden, embedded within its design. This is not unusual – early Christian art from Britain and Ireland made creative use of complex, abstract and riddling decoration, which required rumination and meditation to interpret and unravel. On the Hunterston brooch this imagery also appears to be upside-down – that is, meant to be read with the cross-panel at the top.

But this is something we find on other objects that bear powerful or protective motifs or inscriptions – they are often orientated to make sense to the wearer when they look down, rather than to be the right way up for an audience. For example, a scabbard chape (the mount that prevents the tip of a blade from cutting through its sheath) from the St Ninian’s Isle hoard (Shetland), carries an abbreviated upside-down Latin inscription ‘in the name of the Father’ – the letters are meant to be read by the wearer looking down at the scabbard slung from their belt. The inscription is also worn, despite protective studs which should have prevented casual rubbing, suggesting that it was frequently touched, perhaps for reassurance or in prayer.

The Christian motif embedded in the design of the Hunterston brooch consists of two beasts with open mouths and bared fangs. These beasts are similar to a more clearly depicted pair on one of the St Ninian’s Isle hoard brooches, which like those hidden on the Hunterston brooch, are also upside down.

On the Hunterston brooch, the hidden beasts’ eyes are rectangular amber insets, their top and bottom lips are marked by round pieces of amber and their curved fangs are filled with filigree wire. The fangs can also be read as birds’ beaks, an example of the conscious ambivalence of the design. Within the middle of these hidden beasts’ cheeks are decorative panels bearing clearer versions of just this kind of beast, made from gold filigree. The filigree beast’s eye, cheek and lips are marked by tiny gold granules; on the hidden beasts these are the points all marked by amber settings.

Between the hidden beasts, and about to be devoured by their gaping mouths, is a small panel with four insets arranged in the shape of a simple Christian cross. This motif of a pair of beasts flanking a symbol of Christ is found elsewhere is early medieval art. Sometimes it is very easy to identify, as for example on Anglo-Saxon sculpture at Ruthwell and Bewcastle where the figure of Christ is shown standing on the heads of a pair of beasts. In some cases, the depiction of Christ is reduced to a head, as for example on a shrine (National Museum of Ireland, 1920:37a-c) and a brooch (Grousehall Co Donegal, National Museum of Ireland, 1931:16) from Ireland. More often, a symbol of Christ takes its place: a cross, as here, or a lozenge or three-pointed knot.

This family of images – different ways of rendering a symbol of Christ flanked by a pair of living creatures – has been linked to a particular Christian text, Old Testament Canticle of Habakkuk: ‘you will be known in the midst of two animals’ (in medio duorum animalium innotesceris). This was chanted every Friday in early monasteries and had a special role to play on Good Friday. The phrase was interpreted widely in early Christian thought, linked for instance in the 7th-century writings of the Northumbrian monk Bede to the recognition and revelation of Christ between two people (rather than beasts), as at the Transfiguration and Crucifixion. It seems the text and associated imagery could speak of the wider and crucial concept of the recognition of Christ by the faithful. Certainly, the number of images from early Christian art in northern Britain and Ireland that depict Christ (symbolically or figuratively) between flanked creatures attests to its significance. Because the design is orientated for the benefit of the wearer, rather than an audience, we can suggest that it was more than just a veiled demonstration of religious beliefs, instead offering reassurance or protection to the owner. Brooches inscribed with protective Christian inscriptions or symbolism are also known from the medieval period, suggesting that such a practice was not incompatible with religious beliefs of the time.

On the reverse of the brooch, the decoration is more restricted, limited to discrete panels of interlocking spirals and interlace, together with an inscription in Scandinavian runes added several centuries after the brooch was made. This kind of spiral decoration is one of the key ingredients that were melded together to form a new hybrid art style in early medieval Britain and Ireland. This art style, known by the term Insular art, drew together different influences – old and new, from near and far. It was used to decorate metalwork (such as this brooch and early Christian reliquaries), stone sculpture and illuminated manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels or the Book of Kells. Interestingly, spirals are only found on the reverse of the Hunterston brooch. Were they hidden from view or kept close to the wearer’s body? These spirals were developed from earlier Iron Age Celtic art styles, and were already an old design by the time they were added to the Hunterston brooch. Their meaning is likely to have been reimagined, a conscious use of artistic heritage, and probably carried Christian significance. Spirals are often combined in groups of three, as on the Hunterston brooch, where they most likely allude to the holy Trinity of Father, Son and Spirit.

You can see the Hunterston brooch and find out more about how Celtic art has been reimagined over the centuries by visiting the special exhibition Celts at the National Museum of Scotland from 10 March – 25 September 2016. This features more than 300 treasured objects from across the UK and Europe, assembled together in Scotland for the first time, and explores the idea of ‘Celts’ as one of the fundamental building blocks of European history.

The Glenmorangie Research Project aims to extend our understanding of Scotland’s Early Medieval past and was established in 2008 following a partnership between National Museums Scotland and The Glenmorangie Company. The current phase of research, Scotland’s Earliest Silver: power, prestige and politics will look at the biography of this precious metal as it was used and reused in Early Medieval Scotland.

Scotland’s Early Silver exhibition is at the National Museum of Scotland until 25 February 2018 and follows three years of research supported by The Glenmorangie Company.