National Museums Scotland’s contemporary collections reflect key social, cultural, political, artistic and environmental shifts in the world around us. Whilst researching the material culture of North Sea oil, Assistant Curator, Modern & Contemporary History, Dr Georgia Vullinghs explores the connection between a modern Scottish industry and a 12th century Saint.

The practice of fossil fuel extraction – now under increased scrutiny due to its environmental impact – has been a major component of Scotland’s industry and economy since the 1970s. Offshore drilling for oil was first conducted in the mid-19th century, but it was not until after the 1960s that the extraction of North Sea oil and gas resources reached its current scale. Our collection, which contains objects used by the petroleum industry, samples of crude oil, awards won for innovations in engineering, and vital safety gear needed by platform workers, records and affords understandings of this 20th century Scottish industry.

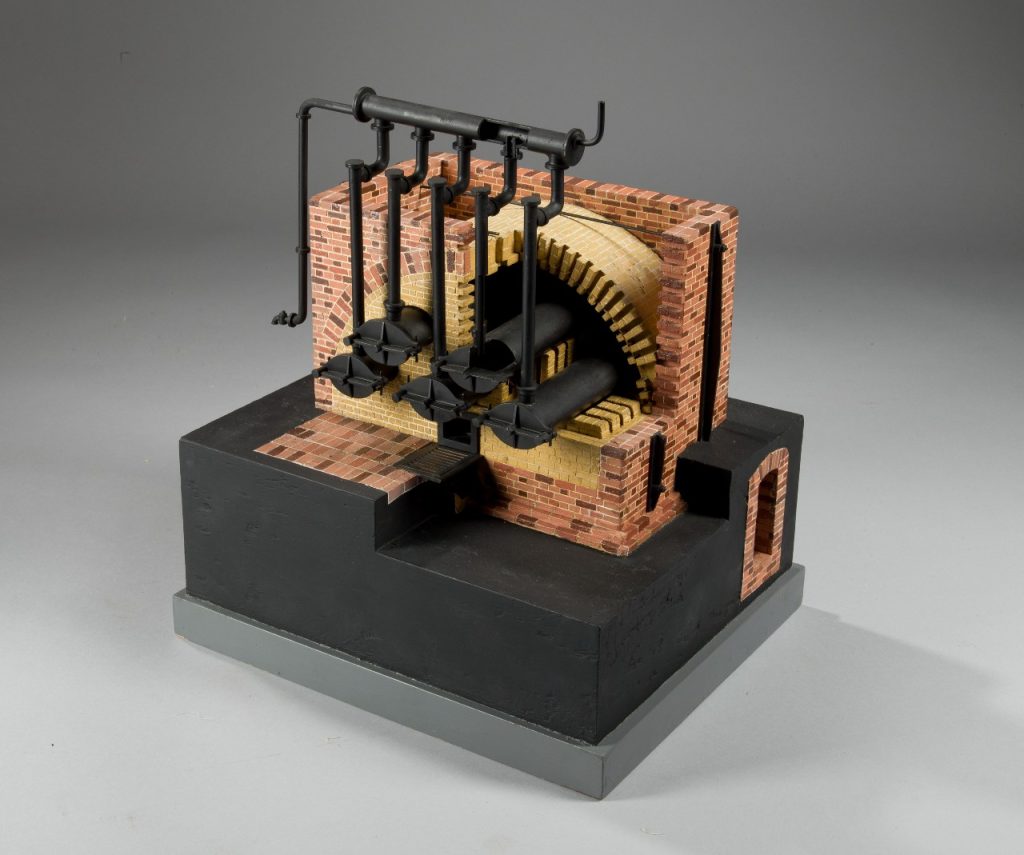

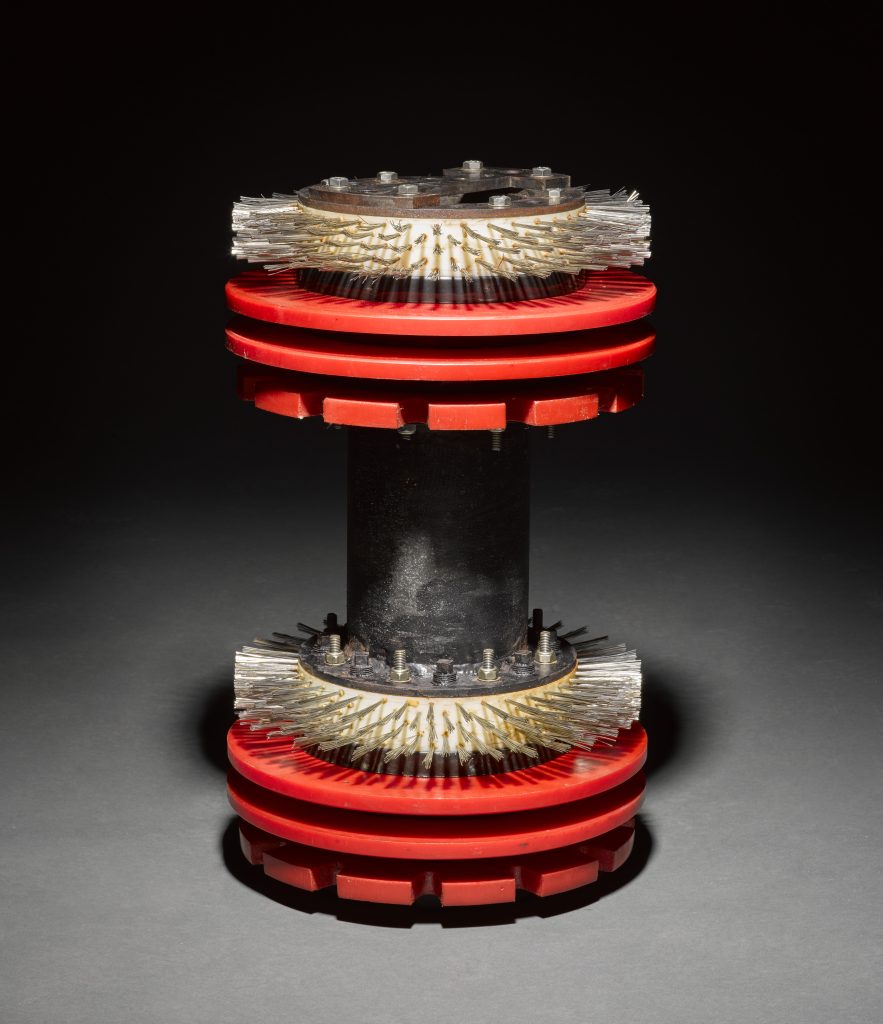

A number of important collection items that contribute to contemporary understandings of Scotland’s industrial past come from the Murchison platform. Built in 1979 as part of a booming industry, the Murchison platform’s huge flare tip, driller’s telephone, control unit, and Pipe Pig (for clearing oil pipes) represent the tools of the industry itself. Moreover, the fact that they are in the museum also speaks of the end of their use. Oil production in the Murchison field was stopped in 2014, and the platform was decommissioned in 2017. The question of how to deal with decommissioned platforms is one which will become more frequent, resulting in an industry of its own. You can find out more about the oil and gas industry in our displays at the National Museum of Scotland, in both the Science and Technology Energise and the Scottish History and Archaeology gallery Scotland: A Changing Nation.

Within the history of 20th century industry, some perhaps surprising links to Scotland’s medieval past are also to be found. Recently, when searching for something to go into the display to replace a returned loan, I was surprised to find an object which celebrated a new, modern, industry, by looking to Scotland’s past. It immediately caught my fascination. This pewter coaster was made to celebrate the inauguration of BP’s Magnus oil field and platform in 1983. The oil field became BP’s most northerly excavation, and the platform built over it was, at the time, the largest in the North Sea. Colossal in scale, its construction was seen as a huge feat of engineering, as well as of human achievement, overcoming the deep waters and challenging weather conditions of the northerly location.

The design engraved into the centre of the coaster is the medieval seal of the Cathedral of St Magnus, Orkney. The design is that of the original 14th century seal matrix, also in the museum’s collections. The image depicts three robed figures, monks, within a gothic arched architectural structure representing the Cathedral. With two figures kneeling in prayer on either side, the central figure wields a sword, and can be identified as the 12th century Saint Magnus. It is this Magnus for who the Cathedral, and oil platform, are named.

During the 11th century, the earldom of Orkney and Shetland was split between two brothers (Magnus’ father and uncle) who ruled together. The Earldom held Orkney from the kingdom of Norway, but also held Caithness from Scotland. By the time their children (Magnus and his cousin Haakon) inherited the earldom, disputes over territory were rife and eventually boiled over into murder, with Haakon killing Magnus. Miracles soon became associated with Magnus’ burial place, and he was made a saint. His nephew promoted his cult to help win back his share of the earldom, building the cathedral and dedicating it to Magnus. Magnus’s relics were housed within the church and became a site of pilgrimage.

What is a medieval seal and medieval saint doing on an object celebrating modern Scottish industry? Since the 1970s, BP had been naming North Sea fields and platforms after Scottish saints beginning with M. Magnus is one in a series including Madoes, Marnock, and Mungo. The connection between Magnus – meaning Great – and the colossal size of the new field and platform was no coincidence. The seal of the Cathedral of St Magnus was, at some point, identified as a suitable logo for the platform. Used on the coaster, it also appeared on posters which decorated the ceremony room and the platform itself at the inauguration. I am still searching for more information about who made the design, and the decision-making process behind it! But there is much we can interpret from the choice.

The history of Saint Magnus was consciously used by BP and their supporters to celebrate the new venture. At the inauguration ceremony on 14 September, 1983, then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, incorporated the legend of Magnus into her speech. Quoting the Nordic Sagas to describe Magnus as “the most accomplished of men in all things”, Thatcher equated the historic heroism of this medieval earl with the modern achievements of BP’s geologists, engineers, and construction workers to “triumph” over severe weather, deep waters, and the size of the platform itself. This modern human building project was also equated to the historic building of Orkney Cathedral, Britain’s most northerly Cathedral. Centuries apart, the two structures were united in their interpretation as significant human achievements in the history of the North Sea region.

Choosing to celebrate the platform with reference to the Orkney saint also connected BP’s work to the local region. In some ways, the name might have helped the engineering and extraction work to be understood as part of Orkney and North Sea heritage, like the Cathedral and Magnus were. The Nordic connections of Saint Magnus, Orkney, and the Cathedral – which became part of the Bishopric of Trondheim in 1153/4 until 1472 – also emphasised a longstanding connection between Scotland and Norway which continued into the modern period through a shared North Sea oil and gas economy.

The use of the seal as the project’s logo worked to visualise and materialise those connections. Seals are historically used in place of a signature. Attached to documents, they physically represent the owner’s approval of the words and decisions within. Used on the coaster and other visual material relating to the inauguration of the platform, the 14th century seal of the Cathedral of St Magnus might also have been intended as a seal of approval for BP’s latest and largest North Sea activity. Ultimately, by incorporating a historic artefact (the seal), site (the Cathedral), and individual (Magnus) in this celebratory coaster, BP purposefully rooted new developments in Scotland’s modern energy industry firmly in the past. Doing so, they could present North Sea oil and gas extraction, with its associated social, economic, and environmental changes, as part of, and approved by, a longer human history of the region.

Forty years later, the place of oil and gas extraction in Scotland’s industry and economy is coming under question. Having been a huge part of Scotland’s economic and industrial identity as well as output since the second half of the 20th century, now the environmental impact of the use of oil and gas resources and our reliance on this industry is under heavy criticism. At the museum, we continue to develop our collections so that we can update displays to tell that evolving story. As new energy technology develops and we look towards futures which are less reliant on fossil fuels, the museum is also collecting Scotland’s renewable energy sector. The growing marine energy sector seeks to harness the unique tidal and wave power of Scottish waters. What role will objects play as we navigate a transition to greener forms of energy and industry?

The coaster can be found on display in the Scotland: A Changing Nation gallery in the National Museum of Scotland.