2022 is a landmark year in Egyptology. It’s been 200 years since the decipherment of hieroglyphs, which unlocked access to written sources from ancient Egypt, and 100 years since the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, whose splendour further fuelled global Egyptomania. Many have celebrated these milestones, but it is also an apt moment to reflect on the history of Egyptology and its colonial origins. Principal Curator Margaret Maitland does just that and explores some of the recent work we’ve been doing in this area.

Ancient Egyptian objects are so ubiquitous in the UK that they’ve become almost synonymous with the very idea of museums themselves. As a result, we often take the presence of Egyptian material for granted. However, few are fully aware of the complex histories of these collections. Many schools in the UK now teach pupils about ancient Egypt, but almost none address Britain’s history of colonial rule in Egypt.

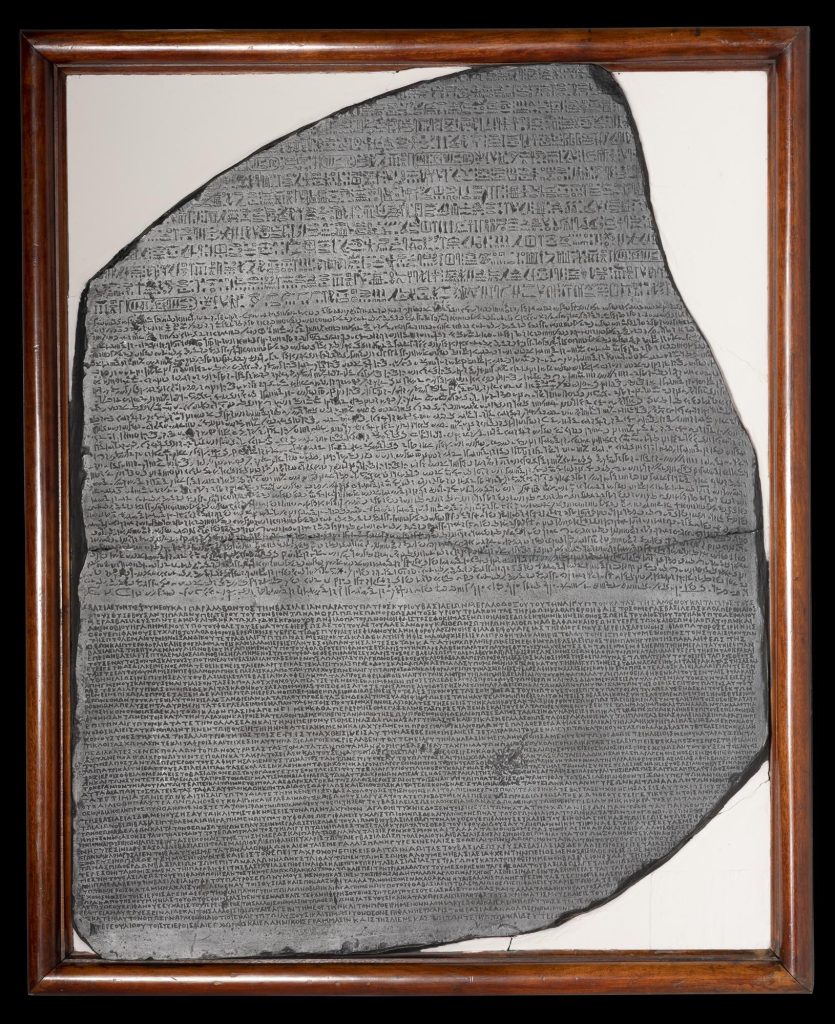

The most iconic ancient Egyptian objects both have un-taught histories. The Rosetta Stone that proved key to decipherment was originally found by the invading French army and then seized by the British army. And the tomb of Tutankhamun was excavated while Egypt struggled to establish its independence from British military control.

Reading the Rosetta Stone

One of the four original casts of the Rosetta Stone, made in London in 1802 to encourage decipherment efforts across the UK, is on display in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery at the National Museum of Scotland. The decipherment of the Rosetta Stone is often presented as a triumph of European scholarship, but the story is much more complex.

When it was first discovered, carved with the same decree written in three languages (ancient Greek, hieroglyphs, and a late form of ancient Egyptian writing called Demotic) its potential to unlock the meaning of hieroglyphs sparked an international race. The French scholar Jean-François Champollion made his breakthrough in 1822, but it’s important to remember that the real key to understanding hieroglyphs was Egyptian.

A crucial factor in Champollion’s understanding was the fact that he learned the Egyptian language known as Coptic (directly descended from ancient Egyptian) on the advice of the distinguished Egyptian professor Rufa’il Zakhûr. This led to Champollion’s realisation that ancient Egyptian must be written phonetically, rather than entirely symbolically. Ultimately, hieroglyphs weren’t just an abstract code to be cracked, it was about finding understanding through communication.

The curse of Tutankhamun?

When the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered a hundred years later in 1922, people around the world were captivated by the golden ‘treasures’ that it contained. The media at the time promoted the sensationalist idea of a ‘curse’. But the real curse has been the distorting impact that the burial’s splendour has had on public expectations of ancient Egypt ever since.

Although the National Museum of Scotland has a few objects related to Tutankhamun on display, research into our collections history suggests that there was intense pressure on museum displays to match the magnificence of Tutankhamun’s treasures. Former Keeper Cyril Aldred, whose ancient Egypt gallery opened at our Museum in 1972 (the same year as the famous Tutankhamun exhibition in London), even went so far as to make a copy of one of Tutankhamun’s golden pectorals. Unfortunately, while we’ve been enthralled by pharaohs and golden treasures, the stories of ordinary ancient Egyptians have all too often been overlooked or erased.

In this anniversary year, it feels especially timely to consider the history and future of Egyptology and museums. Recently, National Museums Scotland has been reflecting on how we research and represent imperial and colonial pasts and how the legacies of these still impact our museums today. We have been researching the provenance of our Egyptian and Sudanese collections, as well as the history of museum collecting and display more broadly and incorporating this information into our displays and public outputs.

Revised displays

We’ve been reviewing existing panels and labels at the National Museum of Scotland and making changes to address historic bias and colonial legacies. For example, this ancient Egyptian coffin and mummified man are on display in our Collecting Stories gallery, which was previously called Discoveries. The old label focused on the Scottish colonial official and engineer Sir Colin Scott Moncrieff, who was involved in dam-building projects on the Nile and brought back the coffin and mummified man as souvenirs.

The focus of the new label is to raise awareness of how ancient Egypt was co-opted into the idea of ‘Western civilisation’, disconnecting Egypt’s ancient heritage from modern Egypt and from Africa. Part of this appropriation was the acquisition of an increasing number of objects by European collectors who framed their collecting as a necessary act which “saved” the antiquities from modern Egyptians.

To counter this, we include a quotation from the Egyptian scholar Rifaa al-Tahtawi, demonstrating that Egyptians were invested in their ancient heritage, even in the 19th century:

“These antiquities are the ornament of Egypt, and it should not be allowed that Egypt be stripped of its finery by sightseers. These monuments remain a history awakening to all past ages, they tell us something of those who lived before.”

Contemporary collecting

We hope to better represent modern Egyptian perspectives and broaden audiences’ perceptions of Egyptian heritage by developing our contemporary collecting in Egypt. For example, a recent addition to the collection is a face mask made in Cairo in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The style of decoration is known as khayamiya, a traditional form of hand-stitched textile appliqué decoration, possibly as far back as the ancient pharaonic period. Khayamiya is exclusively made in the Street of the Tentmakers (Shari’a al-Khayamiyya) in Cairo, a historic covered market built in the 17th century. Today, much of their dwindling trade relies on tourism, which has been devasted by COVID-19. In response to the crisis, artist Essam Ali turned to making protective face masks and selling them online.

The Eye of Horus (wedjat) motif on this particular mask is an ancient Egyptian amuletic symbol of protection and healing, highly appropriate for the mask’s function to protect against disease. The symbol invoked a form of protective magic associated with the god Horus, whose eye was injured and then restored. This mask, and the work of khayamiyya-makers more broadly, is just one example of how Egyptians have been reclaiming their ancient heritage.

Outreach activities

We’ve had the privilege to partner with the AHRC-funded project ‘Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage’, led by Heba Abd el Gawad and Alice Stevenson. The project has sought to communicate the legacies of British archaeology in Egypt, to create opportunities for dialogue with modern Egyptian communities, and to amplify Egyptian voices. This has involved collaboration with Egyptian comic artists, online engagement with communities in Egypt through social media, WhatsApp groups, and online events, and the creation of a web resource in colloquial Egyptian Arabic.

It’s clear that our audiences in Scotland also want to learn more about these complex histories. Earlier this year, we delivered the Museum’s first ever online Schools Assembly to thousands of pupils in over 130 schools across Scotland. Pupils were asked to vote on which questions they wanted to ask us, and it was striking that the question with the most votes was about how the museum had acquired its collection of ancient Egyptian objects. This presented a welcome opportunity to talk about the history of collecting in Egypt and Sudan.

Considering the history of Egyptology, it is perhaps unsurprising that much of our very understanding of Egypt’s ancient past has been coloured by colonial-era biases. For example, the intact burial group of the ‘Qurna Queen’ has fascinated scholars since it was excavated over a hundred years ago, but bias has hampered understanding of the objects and the identity of the royal woman. A focus on categorising the woman’s ethnic identity and the objects in her burial as either Egyptian or Nubian illustrates how often Egyptology has approached Egypt’s southern neighbour, Nubia, as ‘foreign’, rather than considering the evidence the burial offers for shared aspects of Nile Valley cultural heritage. Our recent online event for UK Black History Month was an important opportunity to showcase ancient Nubian history and culture and its significant influence on Egypt. You can watch a recording of the event for free on our website.

Ongoing research

In some of our recently published work, we’ve reflected on the role that restoration played in the Museum’s historic displays of the 20th century. We’ve explored the resulting ethical considerations that we confronted in conservation work for the development of our new Egypt gallery, which opened in 2019.

Ancient Egyptian objects are often exceedingly well-preserved, but the majority of the Museum’s Egyptian collections were archaeological fragments from British excavations approved for export as ‘minor antiquities’ or ‘duplicates’. However, the public’s heightened expectations from the treasures of Tutankhamun probably increased pressure to carry out extensive restoration work in an attempt to return objects to a ‘pristine’ state.

The aim to display a perfect Egyptian past was bound up with problematic concepts of ancient Egypt as foundational to ‘Western civilisation’, with curators and conservators from Europe and the US presented as essential to its understanding. In general, the conservation materials used were found to be readily reversible and our Artefact Conservation team removed the majority of the more misleading restorations. But some objects remain forever altered by their transformation into museum displays.

The history and ethics of collecting and display are issues that we’’re continuing to explore in our latest projects. My ongoing research project aims to contextualise the work of the innovative Scottish archaeologist Alexander Henry Rhind in Egypt. In 1835, Egypt banned the export of Egyptian antiquities without a permit (one of the oldest heritage protection laws in the world). During my research it became apparent that the practicalities of this permit system hadn’t been studied before. To better understand the context in which Rhind was given permission to excavate, I’ve been investigating Egypt’s early heritage protection efforts. I’ve also been identifying Rhind’s Egyptian collaborators. He acknowledged them as ‘experienced and expert investigators’, but their important contributions were subsequently downplayed by later Egyptologists.

Our very own Dr Dan Potter, Assistant Curator of the Ancient Mediterranean, has recently started an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded Research, Development and Engagement Fellowship called ‘Buying Power: The Business of British Archaeology and the Antiquities Market in Egypt and Sudan 1880-1939’. This is the first fully funded research project to focus on the involvement of British archaeologists in the antiquities market in Egypt and Sudan and the impact of this practice on museum collections.

Our collaborative doctoral award-funded PhD project with student Giulia Marinos based at the University of Glasgow is focussed on the history of Scottish museum displays of Egyptian collections in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including examining how Britain’s involvement in empire shaped these displays.

Although the legacies of the past two hundred years weigh heavily, there is clearly an appetite to learn more about these histories, to hear new and different stories, and to work more collaboratively. Hopefully these and other ongoing projects will help us towards our commitment to be more open, transparent and inclusive. We recognise that there is still a lot more work to do.

Thanks to my colleague Dr Dan Potter for his comments on this blog post.