Scottish politics is currently undergoing one of the most consequential and controversial periods in its modern history. Recently, important questions about the status of Scotland within a political union, the United Kingdom, have been posed. These politics are not only played out in formal debates and institutions, but in the production and use of material culture. Georgia Vullinghs, Curator of Modern and Contemporary History, examined five objects in our collections that speak to recent events in Scottish political history.

These five objects are just one part of a larger collection of historic artefacts that tell us about Scottish popular and parliamentary politics. Such objects are physical manifestations of a changing political landscape, and of efforts to shape that landscape from different viewpoints.

The new Scottish Parliament

Since the 1707 Act of Union, Scotland’s parliamentary representation has been combined with England’s (joined by Ireland in 1801). This parliament sits in London, at Westminster. During the 1970s, the question of devolution for Scotland came to prominence, which suggested that a Scottish Assembly should be established. The proposal was rejected in a referendum in 1979. In a second devolution referendum on 11 September 1997, a majority of those who voted supported the creation of a new Scottish Parliament.

A new building was proposed to house the parliament. Located at Holyrood in Edinburgh, it was designed by Barcelona-based architects Enric Miralles and Benedetta Tagliabue. The contemporary appearance of the building, inspired by Scottish industry and design traditions, as well as the nearby landscape, made a statement about its newness. It officially opened on 9 October 2004 and continues to be the meeting place of the Scottish Parliament.

This desk is the final pre-production prototype for the desks in the Scottish Parliament debating chamber. It was made by Ben Dawson, a Musselburgh-based furniture designer and maker. The desk is made of light oak and sycamore wood. It was part of a determinedly modern interior design which is visually distinct from the well-known interiors of the House of Commons at Westminster, with its green leather benches and dark wood panelling that arrange the governing party against the opposition. In the Scottish Parliament debating chamber, the desks were arranged in a semi-circle, symbolising an intention for collaboration.

The desk is also fitted with a ‘Network Congress’ electronic voting system made by Phillips. While it has since been replaced by a different model in parliament, the use of technology at Holyrood also differs from the practice of MPs at Westminster physically making their vote by walking across the chamber. Overall, this desk represents the Scottish Parliament’s aspirations as a new representative body with its own ways of working.

The question of independence

In 2011, the Scottish National Party (SNP) gained a majority in the Scottish Parliament on a manifesto that included the pursuit of Scottish independence. Following this, the Scottish electorate were asked via referendum: ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’.

This welded steel sign was commissioned by the Scottish government to publicise the date of the referendum: 18 September 2014. In the national collections, it represents the way the electorate was encouraged by the Scottish Government to come out and participate in the vote.

The sign was made by apprentices from a Renfrewshire factory. Steel is a historically significant Scottish heavy industry which has faced challenges in the modern era. The commission made a statement about the Government’s intention to support the future of young people in Scottish industry.

On the day, a high proportion of the Scottish electorate turned out to vote. The referendum resulted in a majority No vote, but the question of Scottish independence has remained a contentious one.

Voting ‘Yes’

In the lead up to the referendum, campaigning on both sides of the vote was active and visible across Scotland. A range of material emerged to promote their views, from leaflets, badges and window stickers to key-rings and t-shirts. Produced by the campaign groups and individuals, these objects helped spread awareness of the referendum and were used to express voting intentions.

A mug with the distinctive blue ‘YES’ logo and the words ‘Scotland’s future in Scotland’s hands’ printed on it, was purchased by the donor from the Yes campaign website to raise funds for the campaign. She used it to show her support for an independent Scotland. While political differences can sometimes be fraught, the donor would serve drinks to guests in her home using the mug. Sometimes that was in solidarity over a shared opinion, while other times it was a lighthearted joke when their views towards independence differed. In this way she incorporated her ideas about Scottish politics into her everyday life.

Voting ‘No’

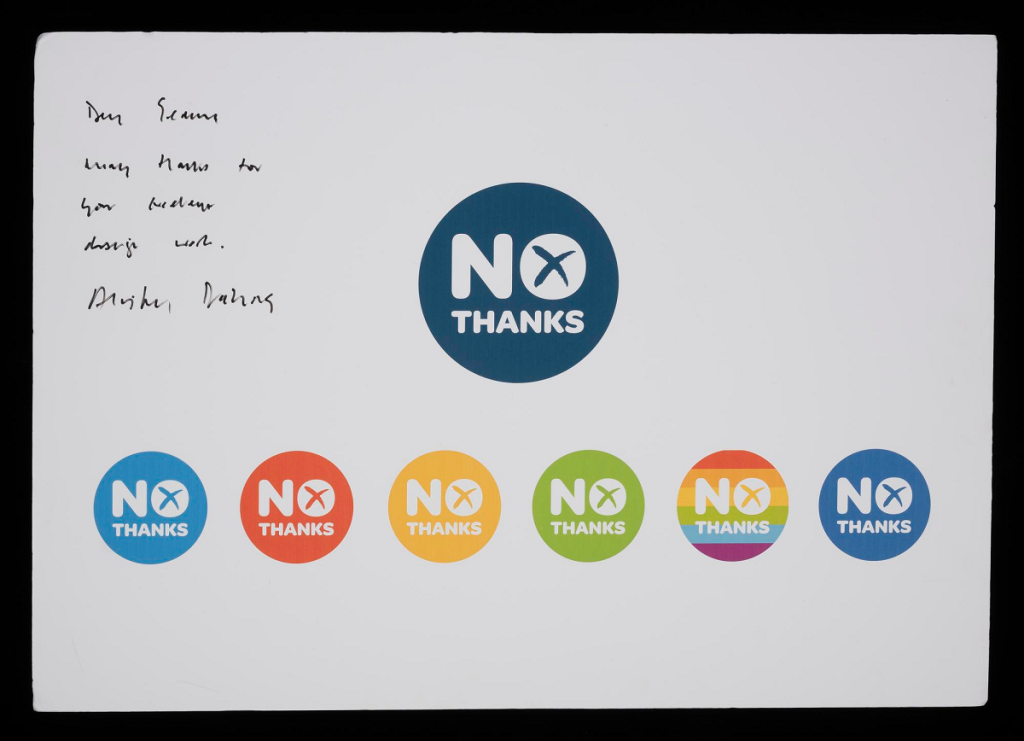

The ‘Better Together’ campaign produced an equivalent range of material. Using the words ‘No Thanks’ the logo expressed a polite but firm response to the question of Scottish independence. This original design artwork proof by Scotland-based designer Gemma Rundell shows the recognisable ‘NO THANKS’ wording over a range of colours associated with different political parties. It has been signed by Alistair Darling, chairman of the Better Together campaign, with a message of thanks to Rundell.

The rainbow striped badge may have been used by some members and allies of the Scottish LGBTQ+ community to show their support for the Union. Its creation demonstrates how the Better Together campaign wanted to be seen as an inclusive one. The cross inside the ‘O’ references not only the Scottish Saltire, but the ‘X’ that voters were being asked to mark on their polling cards to vote against independence.

Brexit: another union under question

Shortly after the referendum on Scottish independence, on 23 June 2016, a majority of the UK electorate voted in a referendum that the United Kingdom should leave membership of the European Union.

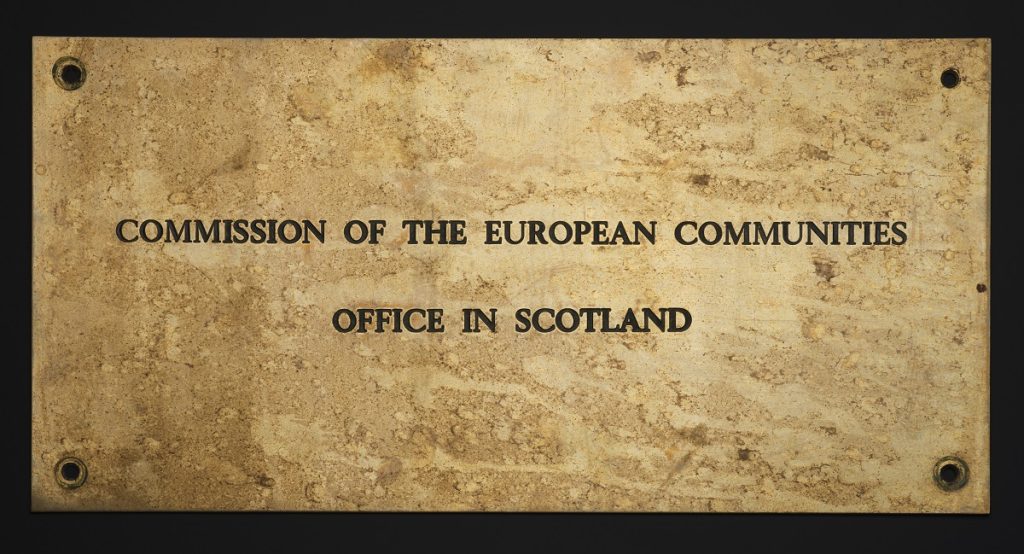

Through the United Kingdom’s membership of the EU, Scotland had its own European Commission Representation. This brass nameplate came from outside the offices of the European Commission on Alva Street, Edinburgh. It was taken down as a result of the office closing ahead of ‘Brexit’ coming into effect on 31 January 2020. It had been there since 1975, when the Scottish office of the European Economic Community was established. The sign’s removal reflected the end of Britain’s, and Scotland’s, participation within the European Union.

Collecting future histories

These five objects are a selection from collections assembled to demonstrate the centrality of material culture in Scotland’s experience of contemporary constitutional politics, and political questions more generally. Such objects come to represent groups, institutions, and different views. Through making, using, and wearing them, these things facilitate engagement with debate.

As constitutional issues continue to be discussed, National Museums Scotland documents contemporary political debates and changes by collecting objects that shape the present and that will form a historical record in the future.