A project exploring Blackfoot quillwork in Scottish museums recently led a remote visit to explore and scan Blackfoot collections held in our collections. Members of the project team tell us about this visit and how digital imaging techniques are allowing for closer engagements with cultural heritage.

Authors: Louisa Minkin, Reader Central Saint Martins; Christine Clark, Assistant Professor University of Lethbridge; Melissa Shouting, MSc Candidate University of Lethbridge and member Kainai Nation; Ali Clark, Senior Curator Oceania and the Americas.

Since December 2020 the Department of World Cultures have been partners on the AHRC funded project Concepts Have Teeth, And Teeth That Bite Through Time: digital imaging and Blackfoot material culture in UK Museums. The project connects Blackfoot people in North America with their cultural heritage held by museums in the UK through digital imaging techniques and spatial web technologies. Its goal is to improve the ability of Blackfoot people to interact with their cultural heritage and recover and shape their own narratives around them.

The project team is made up of Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists and researchers led by Elders from the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Blackfoot objects held by National Museums Scotland have never been visited by Blackfoot people. Many of the Blackfoot objects in the Museum date from the mid 19th and early 20th centuries and were acquired by Scottish colonial administrators, traders and explorers. Blackfoot nations, along with other Indigenous nations in the Americas, were subject to an extensive programme of “ethnographic salvage” by colonial travellers, resulting in large collections of Indigenous cultural heritage items in European museums.

The impact of European settlement on the Blackfoot way of life meant that trading or selling objects for food or other commodities became a means of survival for many Indigenous people. These transactions often reflected unequal power relations between Scots and Indigenous peoples in North America.

The project is focussed on Blackfoot quillwork. Quillwork is considered a “transferred rite” within the Blackfoot Confederacy. This requires one to go through a ceremony to receive the rites to engage in a relationship with all that encompasses the art of quill work. A handful of individuals carry these rites.

The Blackfoot people traditionally use dyed porcupine quills to embroider and weave designs for regalia and personal items. However, the knowledge renewal process was disrupted through the introduction of glass beads and reserve systems by European colonists. The objects being used in the project offer an avenue for knowledge to re-emerge through the techniques used, designs, and conversations that occur. Blackfoot Knowledge Keepers recognised that virtual access would aid their ongoing efforts to revitalise Blackfoot art and traditional knowledge.

It is hard to express in English how important it is for Blackfoot people to connect with our historical items. To the Western perspective, these are just objects, but for the Blackfoot, they are living beings and the museum visits are like being reunited with children who were taken away. Seeing and touching the items allows Blackfoot people to reconnect with the material and their ancestors. The moment of first encountering the objects is an epiphany in self-identity – these objects help to understand who I am because they are part of who I am. Blackfoot artists want to learn how to make our art and they need to see the traditional designs, materials, and techniques. Even without being able to touch the items, the Blackfoot people can connect with them.

Danielle Heavy Head, Blackfoot Digital Library

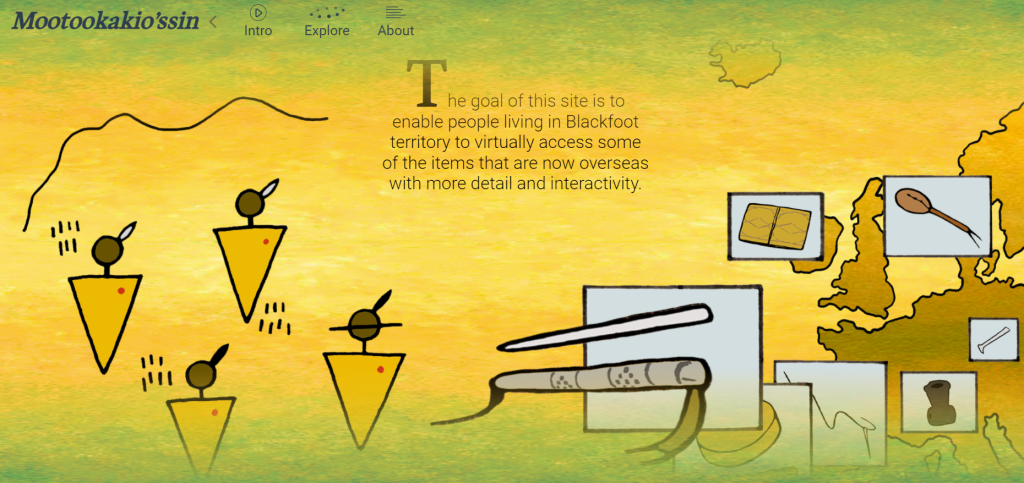

Using digital imaging processes, the project is creating three dimensional digital models and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) of quillwork objects. The models and images are then hosted online by the Blackfoot Digital Library microsite Mootookakio’ssin to serve as a resource. Mootookakio’ssin, established in 2018, is the sister project to Concepts Have Teeth and translates to ‘distant awareness’ in English. In this way, people living in Blackfoot territory are able to access items that are overseas virtually with interactivity and detail, rebuilding connections and assisting in processes of knowledge renewal.

Not having access to these items has hampered the ability for certain areas of knowledge to be awakened. Each object is tied to ancestors and their teaching. Reactivating the objects creates a path to reconnect with Blackfoot knowledge and Blackfoot identity, a process known as ‘kakyosin’ (coming to know) which occurs through the spiritual connection within the alliances of kin and natural law. The objects are a map of Blackfoot traditions, a history of craft and material knowledge, and of relations between Blackfoot people and settlers. Yet, access to them remains limited and most Blackfoot people have little knowledge of what exists where.

The Blackfoot People are so tied to nature and the landscape, so you look at these items and try to imagine what they saw. Our culture and our belief system are captured in this art — there’s a lot of value in that.

– Blackfoot Elder Jerry Potts

Prior to the COVID 19 pandemic, we were planning for a few members of the project group to visit some of these items at the National Museums Collection Centre. Once it became clear that this visit wouldn’t be happening, a new research question emerged: how might we design a remote viewing experience to support the cultural revitalization for Indigenous communities when in-person access is not an option? We set about to stream a live video of the items at National Museums Scotland to a gathering of Blackfoot Elders in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

In preparation, curatorial staff at National Museums Scotland took record images of objects identified as Blackfoot or Plains and circulated these and database records among Blackfoot Elders. The project team took some time selecting items from our collections for the remote viewing in collaboration with Blackfoot people. A selection was made for the remote viewing through ongoing conversations over several months.

We were uncertain as to when the Collections Centre would re-open for external researchers and fixing dates was slippery as pandemic regulations across England and Scotland shifted, loosened and tightened. As vaccination rates in the UK grew the remote visit was tentatively scheduled for September 2021.

The UK project team based at Central Saint Martins and the University of Southampton came up with a plan to work around this. A Zoom feed for basic communication was set up, along with separate higher resolution stream running on a team member’s server accessed through a browser window. We used multiple smartphone cameras at the National Museums Collection Centre to give the remote viewers a sense of the space we were working, in as well as closer views of items.

They remembered stories they had been told on a visit to Blackfoot territory about the Chickadees, small North American birds who can dart their eyes out to see from multiple perspectives. They were also influenced by the creative work that their students and collaborators were doing to maintain and develop art practices and education over the lockdown period. This was done creatively using remote cameras to explore their artworks and thinking through strategies of performance to camera and the improvisatory staging and framing of an online event.

As restrictions continued to ease, the two-day visit in September was confirmed. Time-zones and the opening hours of the Collections Centre meant we had a two-hour window for the remote viewing in Edinburgh, so we were especially attentive to the coordination and choreography of movement and care of items through the process.

Blackfoot Elders came together at the University of Lethbridge Penny Building where the team had set up several large screens and a conference mic with enough space for social distancing. Other project members joined remotely through the Zoom call. Team members working with the items in Edinburgh joined the session with their smartphones and earphones in order to hear directions, questions and comments from Blackfoot Elders remotely.

“The items documented within this project opened doors for conversations that are holistic in nature, and that welcome the collectiveness of knowledge translation and transmission within the Blackfoot Confederacy and its people,” explains Melissa Shouting, master’s student, artist and research assistant. Shouting was one of the Blackfoot members that visited with the objects in British museums, alongside representatives from all four Blackfoot tribes, sharing and connecting their experiences and interpretations of the knowledge shared through the items.

“Indigenous knowledge transfer is reliant on personal lived experiences and the interpretation of the knowledge shared through oral history practices, creation stories, ceremonies and kin-based knowledge systems,” says Shouting. This mode of knowledge translation has the ability to connect individuals to the knowledge that is attached to the objects revealing a connection with their ancestors. In sharing this knowledge, it allows us to understand not only the objects but the purpose, the history and the teachings associated with crafting together such objects.”

We began the remote viewing with a prayer. Over the two-day session we viewed 24 objects. Some passed over quickly, and we lingered on others with camera work to focus upon details as directed by Elders. Looking closely at a horse crupper revealed a pair of Levi jeans had been repurposed on the underside of the item, giving it weight and supporting the intricate beadwork on the other side.

The second day involved a smaller remote group who brought their thoughts to the table and looked again at some of the items in detail, hearing stories and insights as we did so. Melissa noticed that the cradle board has two distinct patterns. This may indicate a contribution from each of the two tribes that the child had kinship ties to. Moss bags were more common amongst the Blackfoot, so the cradle board might have been made by the child’s mother who may have chosen to marry a Blackfoot man. The designs around the edge of the cradle board look similar to that of the southern tribes located in the United States. The hood’s Blackfoot designs and the cradle itself could be interpreted as a binding together of communities.

The next stage is to build the three-dimensional models and process the RTI imaging. You can follow the progress of the project here. The collection will be a resource for contemporary Blackfoot artists and educators. In Dr. Jackson 2Bears’ Indigenous Art Studio classes at the University of Lethbridge, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students have already begun to create responses to Mootookakio’ssin.

Further reading

Bastien, Betty. Blackfoot ways of knowing: the worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi. University of Calgary Press. 2004.

Brown, Alison K. First Nations, Museums, Narrations: Stories of the 1929 Franklin Motor Expedition to the Canadian Prairies. UBC Press. 2014.