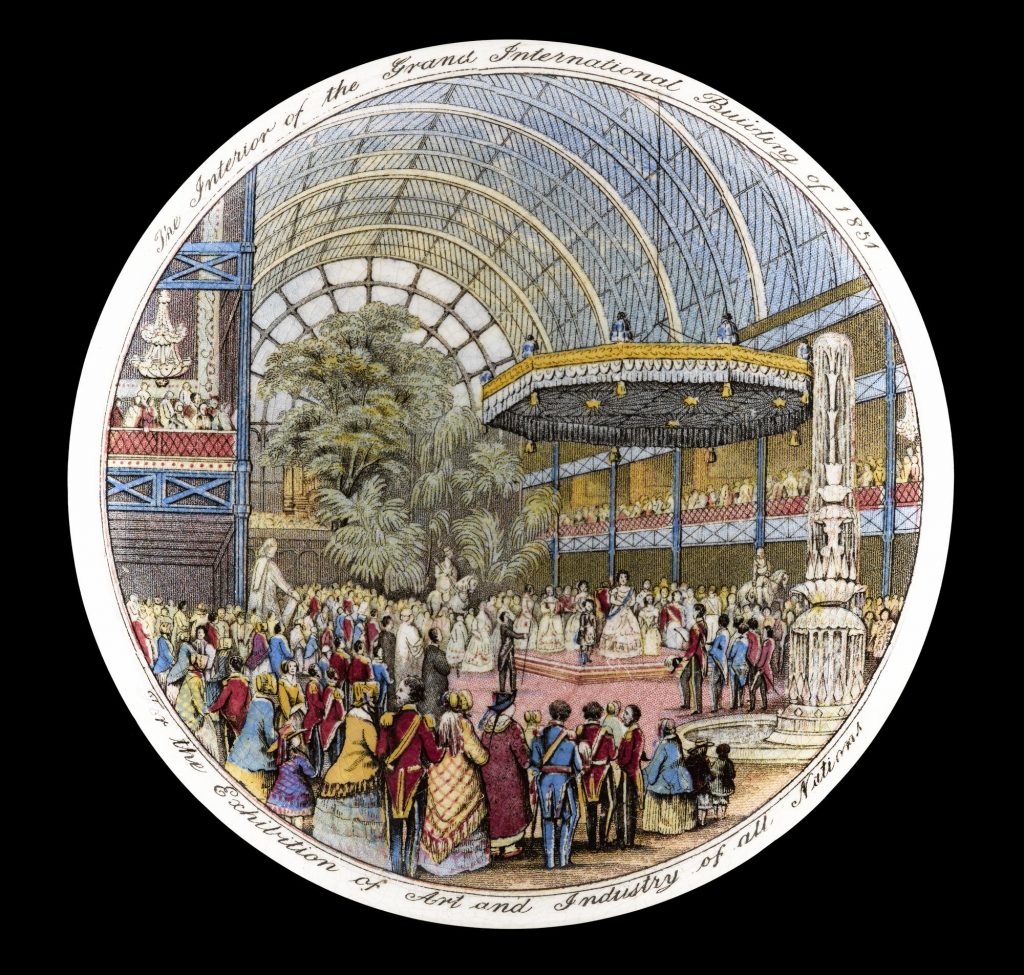

On 1 May 1851, The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations opened in a huge, purpose-built Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London. 170 years later, The Great Exhibition’s design legacies are still being felt. Claire Blakey, our Curator of 19th-century Decorative Arts, explores the story of the event through objects in our collections.

The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria accompanied by Albert, Prince Consort, who had been instrumental as one of the creators of the first international exhibition of manufactured products. Raw materials and machinery were also on display, including showcasing the production of cotton, from spinning to finished cloth.

Despite Britain’s position as a leading manufacturing nation, there were real concerns about the quality of British design and fears that British manufacturers would lose trade to other countries. These fears had seen the government adopt a variety of initiatives to improve design education, including setting up new design schools. The exhibition was to provide another chance to inspire the country’s workforce with groups of factory workers visiting on excursion trains from all over Britain.

‘To be aware of our deficiencies is the first step towards amending them; and there is no maxim safer than that which teaches us not to undervalue our rivals: our Industrial Exhibition will have had this good effect at least.’

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue. The Industry of All Nations, London, 1851.

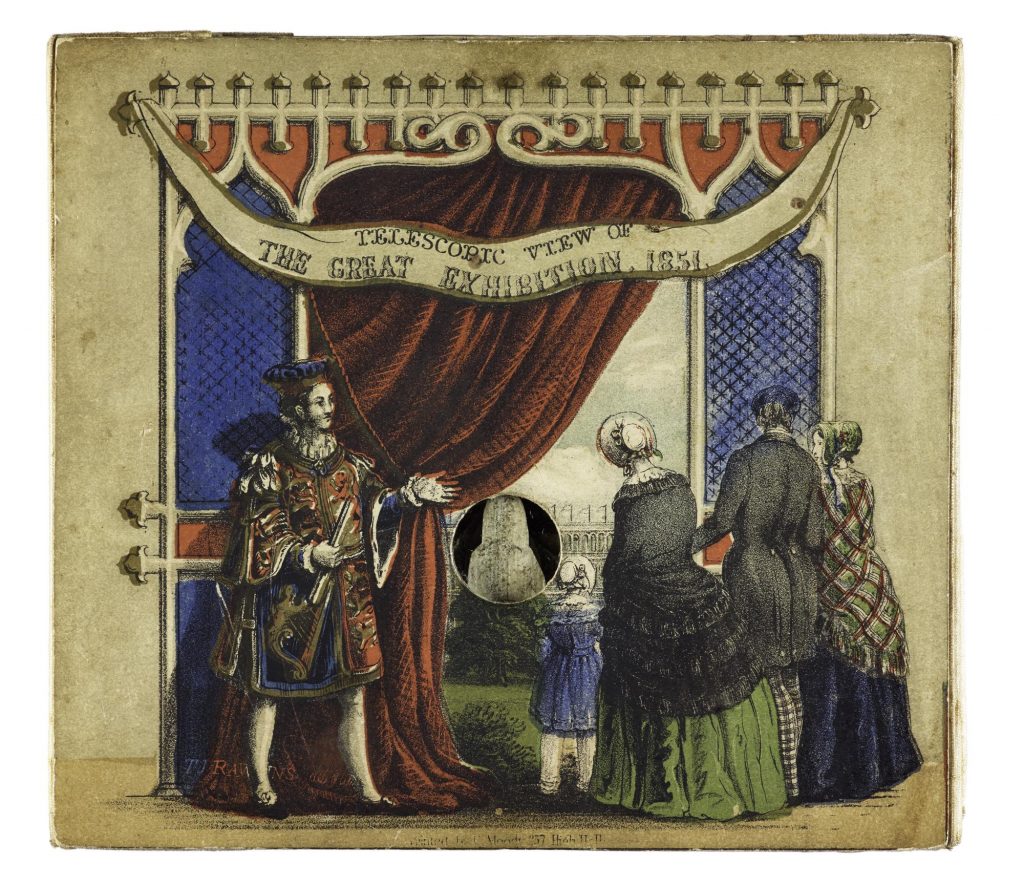

The exhibition ran for six months until October 1851 and was a huge success: over six million people paid to visit, about a third of the British population.

For the millions of visitors, an important part of their day out was buying a memento to take home. A vast range of souvenirs was produced, from transfer-printed ceramics to engraved shells, as well as catalogues, guides and books.

Despite the reference to ‘All Nations’ in its title, the focus of The Great Exhibition was firmly on Britain and Europe. The Indian Court, with its howdah displayed on a stuffed elephant and the Koh-i-noor diamond — the largest known precious stone at the time — was one of the most popular sections. Its displays, and by extension those of the rest of the British Empire, were created with the aim of presenting them very much as a resource to be exploited and a market to sell British goods to.

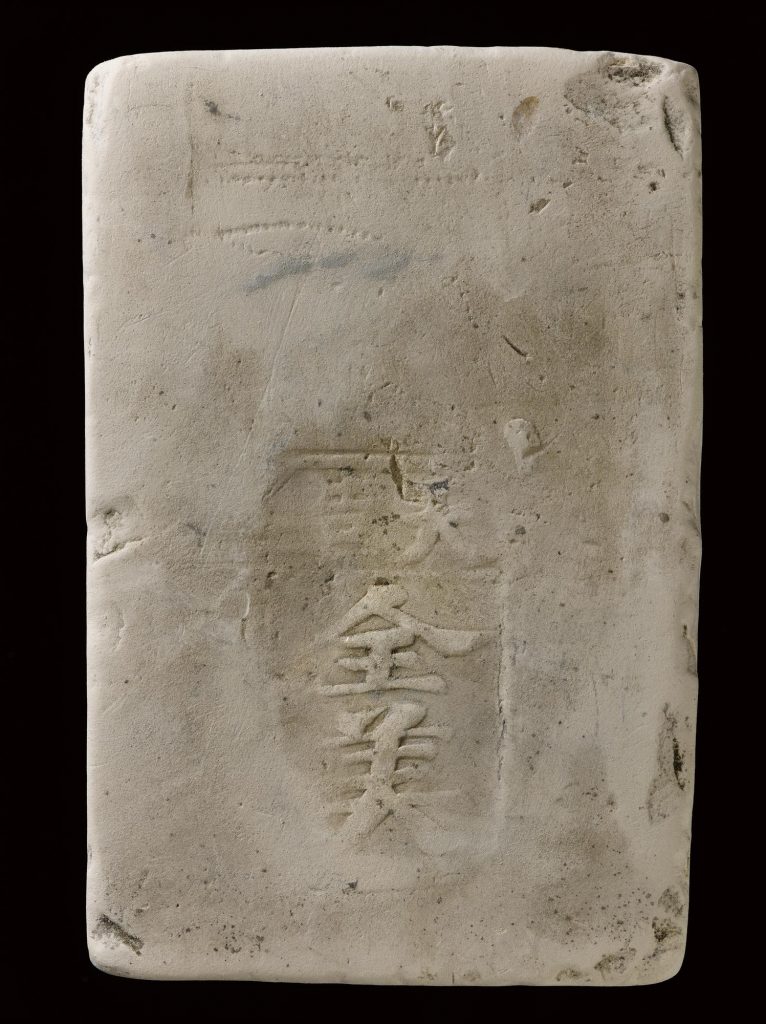

Even in the Raw Materials division, only a minority of the material on display came from outside Britain and Europe. An exception can be seen in the form of a sample of porcelain clay from Jingdezhen, China which was presented to the museum in 1853, alongside other samples which had been on display at the Exhibition. In the Fine Arts division, this absence was even greater. Accordingly, the prizes awarded during the Exhibition went overwhelmingly to British and European exhibits.

Despite its commercial success, the Exhibition was not seen as triumphant in terms of British design. Many critics were dismayed by what they felt was the low quality of many of the British exhibits. However, the profits of The Great Exhibition were used to create a cultural district in South Kensington, which included the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Royal Albert Hall, establishing a permanent hub for British design and culture in the city.

Here in Edinburgh, The Great Exhibition’s legacy can be seen in the founding of the Industrial Museum of Scotland in 1854 (now part of National Museums Scotland; find more about our history here.) Much like the museums in South Kensington, the aim was to improve design education and the quality of industrial goods.

The government Department of Science and Art aimed to educate the public in what it considered ‘good taste’ in design. The inspirational and educational power of the museum displays were seen as a vital part of this. The decades that followed were to see many new artistic movements that transformed design.

Today, our collections and displays allow us to tell a much broader and international design story, showing the inter-connectedness of both techniques and designs. We continue to collect in these areas to better represent these stories and to move away from the very one-sided, selective view given by the Great Exhibition 170 years ago.

Most of the objects in this post are currently on display at the National Museum of Scotland in our Design For Living gallery (Level 5). Book your visit today and enjoy our world class collections in person.