Our natural sciences collection includes an internationally significant collection of marine mammals. In this post, Curatorial Preparator Georg Hantke explores how that collection continues to grow and how it informs new understanding of the whales, dolphins and porpoises found around the coasts of Scotland.

This post contains images of dead animals

Whales have long been collected in Scotland. Once, this was for hunting: their oils were highly sought after during the Industrial Revolution and, to a lesser extent, their flesh for consumption. Collecting whales for scientific purposes is a more recent activity, which offers new insights into their little-known ways of life, and it is an area of work in which National Museums Scotland is heavily involved.

The most common whale in Scottish waters is the minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), which is the smallest of what are known as rorqual whales. These animals belong to the family Balaenopteridae, including the largest whales of all, the blue whale (B. musculus) and the famous humpback whale (Megaptera novaenagliae) with its enormously long pectoral fins, a less frequent sight in Scottish seas.

The most diverse, yet least well-understood, group of whales are the beaked whales, Family Ziphiidae. There are 23 known species and more may yet still be discovered. They are the most elusive group of whales and spend the majority of their time out at sea or diving deep into the ocean in search of food. Unlike most other whales, beaked whales only ever spend a short time at the surface and rarely breach. Owing to their size and behaviour, many species have never been hunted by humans. Therefore, much of what we know today comes from dead animals found by chance on beaches.

Only four species of beaked whale occur in British waters. These are Cuvier’s beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris), northern bottle-nosed whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus), Sowerby’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon bidens) and the rarely encountered True’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon mirus). Beaked whales are solitary or live in small groups, making mass strandings a very rare occurrence. Recent mass beaked whale mortalities reported in the Irish Sea in 2018 are thought to be linked to naval military exercises using mid-frequency active sonar at sea.

Anthropogenic (or human-made) ocean noises, ship strikes, diseases, freak storms and pollution all negatively impact whale populations. Warming oceans have changed the distribution of whale species and new species are now being encountered along the Scottish coasts, while species that used to be common around Scotland are now found much further north. A classic example is the occurrence of the striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) that was first recorded in 1988 and is now a common sight, while the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) becomes rarer, as it has moved into northern waters.

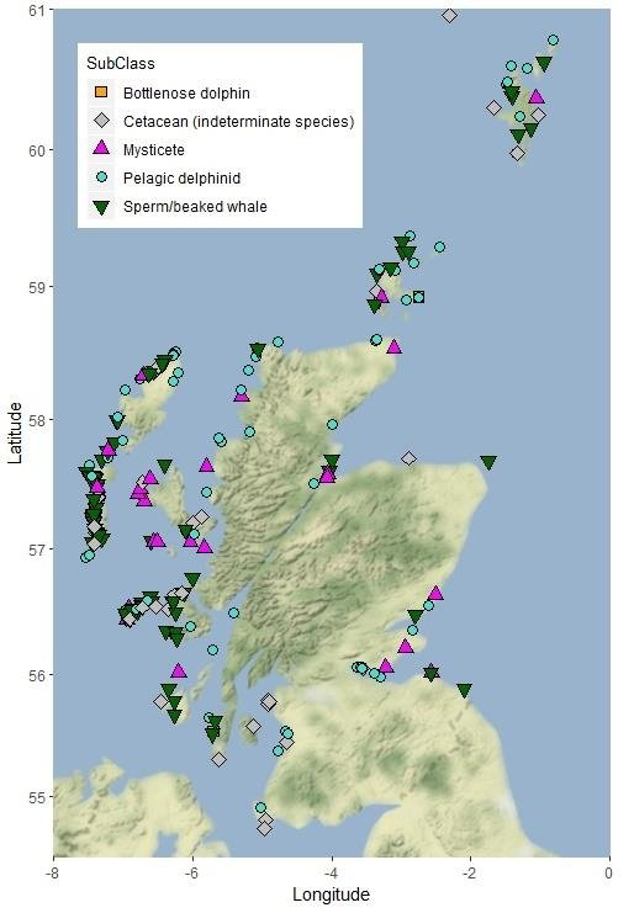

How do we know that the distributions of whales and dolphins are changing? The Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme (SMASS), with the help of hundreds of volunteers across Scotland, report, record, and collect stranded marine mammals every year. The highest recorded number of stranded animals was over 900 in 2018. Although this seems like a very scary number to read, especially for a country as small as Scotland, we are still not able to say if this is abnormal or if it is due to the growing awareness and increasing number of people who are reporting stranding events to the organisations. Most likely, both factors contribute to the high number of marine mammals reported in Scotland.

To me, collecting whales for the Natural Sciences collections is an opportunity most people will never experience. Although I do not wish for these magnificent animals to die, my contribution to the Natural Sciences research collections and to the broader body of scientific knowledge on whales is based on collecting, preserving and studying these specimens. Our work helps to get the most knowledge we can from these animals.

There is still so much in the natural world which we still don’t know about. There may be hundreds, if not thousands, of published papers on cetaceans, yet it is only a drop in the ocean compared to what we need to know. “How does a whale’s body function, what kind of diseases do they carry, and how and on what do they feed?” are only some of the questions that still need answering.

Anatomical and morphological studies on these animals are surprisingly uncommon. Bone diseases and other forms of pathology are underreported. Chemical pollutants found in their blubber are giving us clues about their health status and the health of the oceans, because, being at the top of the food chain, they accumulate pollutants from their prey.

I have been lucky enough to have the chance to attend post-mortem examinations and collections of stranded whales. It is often gruesome, but none the less, these are valuable opportunities for finding out more about whales, dolphins and porpoises. We process around 70 cetaceans a year in the Vertebrate Biology section of National Museums Scotland and, as a result, we are always discovering new information about these animals.

It’s wonderful to see guest researchers from all over the world studying the specimens or data from our collections and being able to work collaboratively with them. For me, it’s also about being out in nature, meeting new people, working on something most of us have never seen and will never otherwise have the opportunity to see.

This work has brought me to some of the most remote places in Scotland. Adventure awaits you on every trip you take. Sometimes you are far away from any help and you must rely on what you know; if it’s bad weather, camping in the field for days in snowy or icy conditions; organising an entire team within minutes; or obtaining last-minute funding.

At the beginning of the year, I was lucky enough to go on a whale collecting trip with Scottish wildlife cameraman and photographer Doug Allan. Not only did the whale turn out to be the first record of True’s beaked whale in Britain, but it also brought me to Cape Wrath Sutherland, a place neither Doug nor I had visited before. It is those things that make a trip memorable while being rewarded with studying one of the least known species of whales in the world.

A massive amount of time, effort, energy and money lies behind collecting each whale specimen. Without the help of so many people, a single collecting trip could easily cost several thousand pounds or could simply fail. Luckily, amazing people are always there to help out, support your ideas and share the struggle. When you are stuck on a remote beach, facing several tonnes of dead whale, how do you get it back to the lab, or even off the beach? Such things have to be considered carefully to keep everyone safe, but often these must be dealt with immediately giving you only giving you minutes to make clear decisions and finding solutions everyone will be happy with.

If you wish to find out more about my and our work or maybe become part of the SMASS volunteer network, let us know.