Earlier this year, I worked alongside Emily Taylor, Assistant Curator of European Decorative Arts, focusing on organising and cataloging the spectacles collection. From September 2019 – January 2020, we worked through around 200 items, updating their object descriptions, photographing them with their accession numbers and re-storing them in new trays lined with Plastazote foam.

Before this project, I had never read much about the history of spectacles. I was curious to find out more about the development of styles – some of which are surprisingly daring, and the personal stories surrounding them. So I did some research.

Here are some of our favourites:

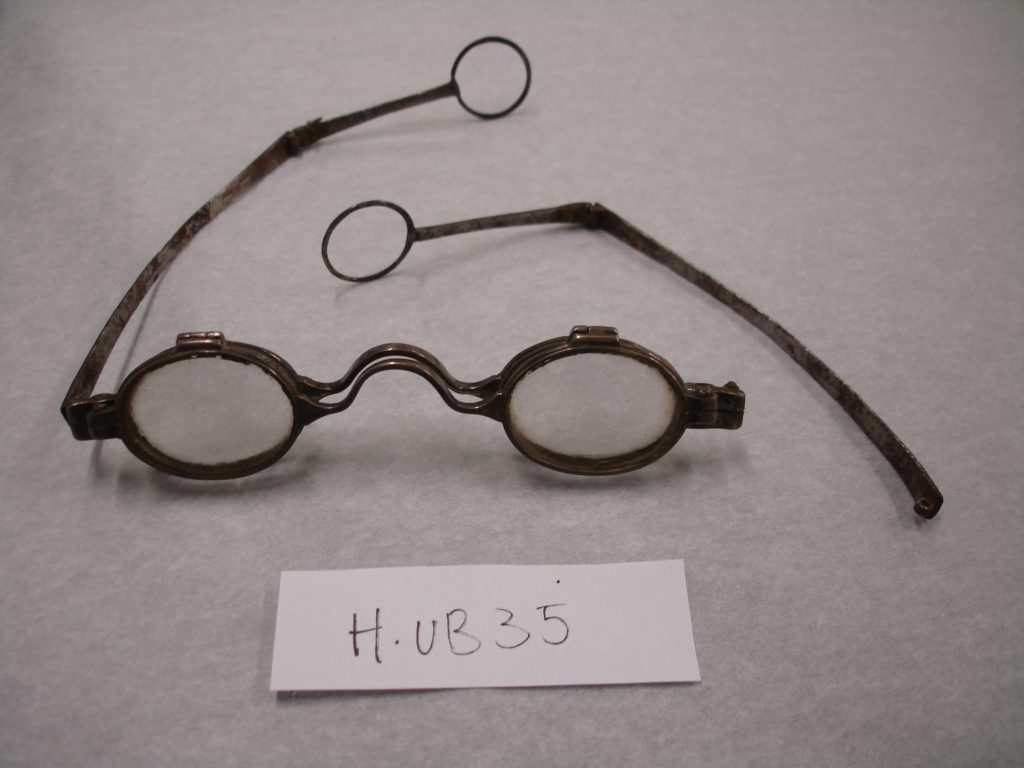

These are a pair of ‘Nuremberg’ spectacles, a style very common in Britain throughout the 17th and into the 18th century. The C-shaped bridge is wrapped in twine – most likely flax. I imagine perhaps the owner of this pair had wrapped this on themself to make them more comfortable and to help them stay seated on their nose. The pair are accompanied by a lovely little case of embossed brown leather and paste board.

British, c. 1780-1840

This style could be referred to as a type of bifocal lens – known as an ‘Addison Smith’ variety, patented in 1783. An additional pair of lenses are hinged at the top, enabling the wearer to flip them down for close

work.

The increased availability of newspapers and literature in the 18th century helped to fuel a demand for reading glasses. The development of sides or ‘temples’ is thought to have occurred at some point before 1730. This pair possess another interesting characteristic, unusual to today’s glasses wearers – the circular feature at the end of the temples. These would allow the wearer to secure their glasses neatly into their wig – as was the fashion throughout the 18th century.

Although these undoubtedly remind me of the iconic sunglasses worn by John Lennon in the 1970s, this dainty pair with circular blue tinted lenses and a fine steel frame – in fact date to the late 19th century. Tinted lenses, often coloured green or blue, had been prescribed as a therapeutic measure to aid problems with vision since the mid 18th century.

The accompanying leather case is printed with ‘F ROBSON OPTICIAN, 46 DEAN STREET, NEWCASTLE-on-TYNE’. After a quick search, I found that Robson Opticians had established their practice in 1867, and are still open in Newcastle today – a very satisfying discovery.

These are a really intriguing pair. The striking design with four tinted D-shaped lenses came to be known as ‘railway spectacles’. In the days of coal powered steam engines, the side lenses were intended to shield the wearer’s eyes from any cinders or smoke whilst travelling in open air train carriages or standing on a platform. The two additional side lenses acted as a form of protection, but could also be folded inwards, sitting over the main pair to combine their strengths.

British, c.1750-1850

British, c.1930

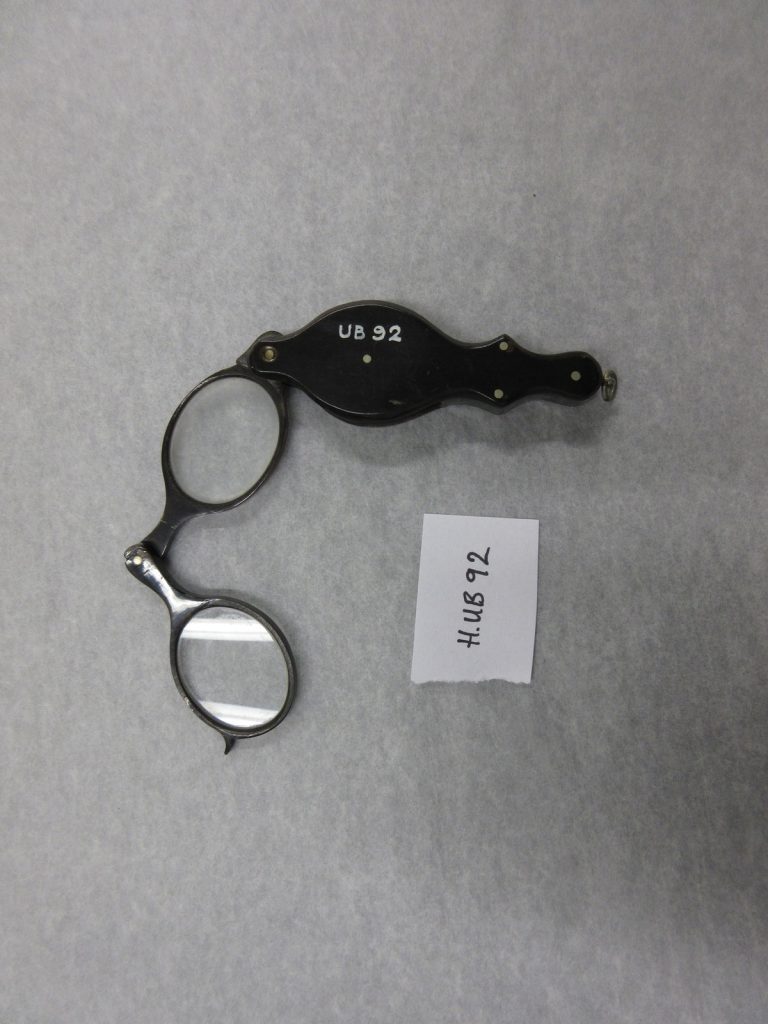

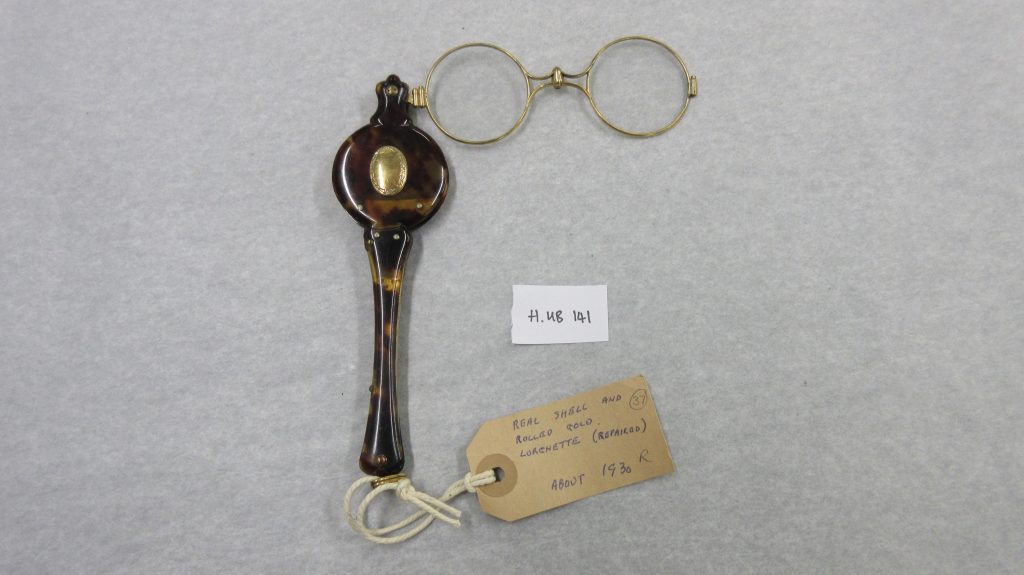

Here are two examples of the Lorgnettes in the collection. Believed to have been invented sometime around 1770, they are designed to be held out in front of your eyes by a handle which, like these examples, often doubled up as a case. Most are cleverly crafted to fold up neatly into the handle so they can easily be kept in your pocket. Lorgnettes soon became an immensely popular addition to any theatre or opera-going outfit, often used just as much as an accessory as a method of advancing vision.

The first is an early example dating from 1750-1850 with a horn frame and case. Hinged at the bridge and the side, the lenses pivot round to fold neatly into the small handle.

Second, is an ingenious design using sprung hinge mechanisms to allow the glasses to flip quickly in and out of the elegant tortoiseshell case. This pair dates to around 1930.

Another of my favourites is this optician’s set of lenses used for testing a patient’s eyesight, consisting of eight pairs of spectacles with lenses of differing strengths. The frames are made of dark brown horn, fastened together with a swivel hinge between two covers.

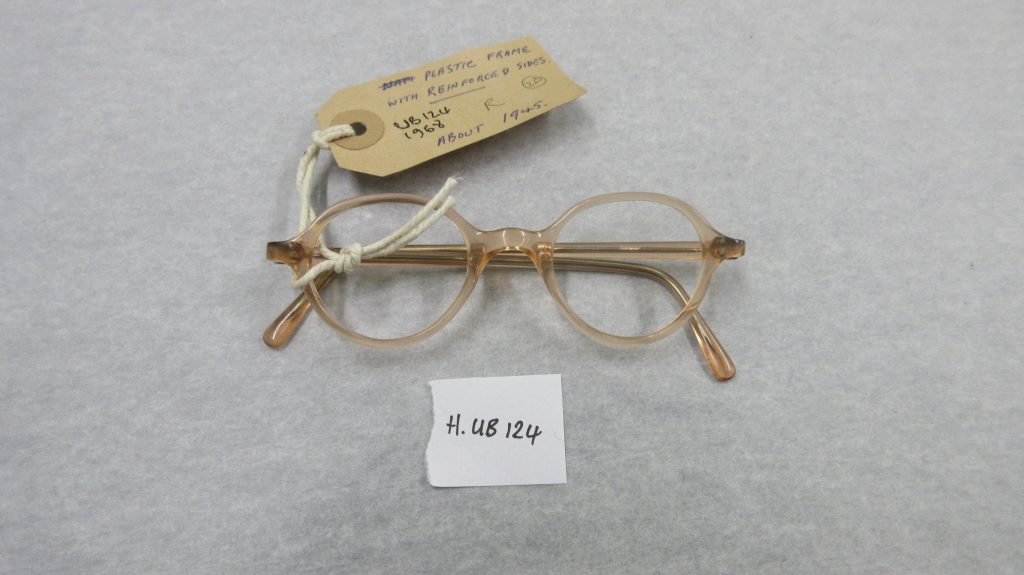

This ovoid shaped pair with pink tinted transparent frames date from around 1945. What is most poignant is the original description given to them. Whoever had initially catalogued this pair in 1968 had described them as ‘flesh coloured’. Without an accompanying image, this immediately makes you question: well whose “flesh” are they referring to here? It is evident, in this instance, the curator was only considering those with white skin. The description has since been altered and now describes them as

having ‘pink plastic frames’.

In a sense, these glasses demonstrate one small way in which museums can shift towards a greater level of inclusivity. In this case, by simply altering the difference between two words – ‘flesh’ and ‘pink’. But words matter. Museum staff are continually reconsidering and updating object descriptions to align with contemporary research and attitudes. We can learn a lot about the change in societal norms and opinions through observing the adjustments in the language used to describe one material object over time. These choices of language give us an insight into what was considered the most important or interesting aspect about an item at the time the description was written. It also allows us to contemplate what might be missing, and for what reason.

Links/References:

https://www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/museum/online-exhibitions/virtual-spectacles-gallery.html

https://www.robsonopticians.co.uk/about/

Winkler, W. (1988). A Spectacle of Spectacles : Exhibition Catalogue : the Exhibition “A Spectacle of Spectacles” was first shown in the United Kingdom at the National Museums of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1988/89. Leipzig: Edition Leipzig.