As the clocks change back to Greenwich Mean Time and the days shorten towards Winter Solstice, the sensation of passing time seems more acute than ever. A few days ago I visited our National Museums Collection Centre at Granton in North Edinburgh where time’s disorientating effects are set out in concrete form. The Collection Centre is home for many of the objects and specimens not currently on display in our galleries, stored with care so that we can research items in depth and draw on the breadth and variety of our collection to the benefit of our changing displays, temporary exhibitions and loans programme. We stood in the hangar-like space of one store and surveyed motor cars (ranging from an 1897 Arnold Benz to a 1985 Sinclair C5), parked neatly in front of slabs of neolithic rock art from Dumbartonshire. Thousands of years lay between them, but they had equal power to inspire.

Once I’d returned home, this juxtaposition of objects from different moments of existence sent me back to the enduring work of Edinburgh-born geologist and natural philosopher James Hutton. Several of my curatorial colleagues have recently reminded me of his relevance to contemporary debates about the human impact on the environment, the fragility of the present, and the inevitability of future change. His concept of ‘Deep Time’, originally described in the 1780s and 90s and published in his ‘Theory of the Earth’ has a decidedly modern ring: ‘We are… led to see a circulation in the matter of this globe, and a system of beautiful economy in the works of nature. This earth, like the body of an animal, is wasted at the same time that it is repaired. It has a state of growth and augmentation… of diminution and decay.’ Hutton’s words form a revolutionary message that challenged traditional understandings of creation and transformed our understanding of millennia, urging us to look anew at the evidence which lies all around us in Scotland’s sublime and ancient landscapes.

Sarah Laurenson, our curator of modern and contemporary history, has drawn my attention to two categories of objects in our collection which bring Hutton’s ideas into sharper perspective. Dating from his period, our collection of eighteenth and early nineteenth-century agate brooches demonstrate in miniature both the timeless beauty of Scotland’s natural resources and the violence of geological change. The delicate suggestion of sedimentary layering and volcanic activity in agate’s polished surfaces might have reminded any well-read follower of new theories in fashionable ‘Enlightenment’ Edinburgh or Glasgow of Hutton’s almost biblical statement that ‘with respect to human observation…. this world has neither a beginning nor an end.’ Choosing agate jewellery in the 1790s was truly a sign of learning and fashion, connecting the wearer with prehistory and the dawn of time.

Closer to our time the intangible record of snow patches has inspired a Huttonian acquisition for the early twenty-first century. Snow patches are areas of perpetual snow, a little like mini glaciers, that last throughout the summer in Scotland’s mountains to be covered over by new falls in the autumn. Snow expert Iain Cameron has been measuring them for the Royal Meteorological Society as important indicators of the effects of climate change over decades. We have a piece of virgin granite from his investigation of the most permanent patch, known as the Sphinx, which is located on Braeriach (Britain’s third highest mountain) in the Cairngorms. Exposed to sunlight only seven times in the past three centuries, the rock is pristine, untouched by organic life forms such as lichen. I’d try and make a souvenir of it if I were living two hundred years ago!

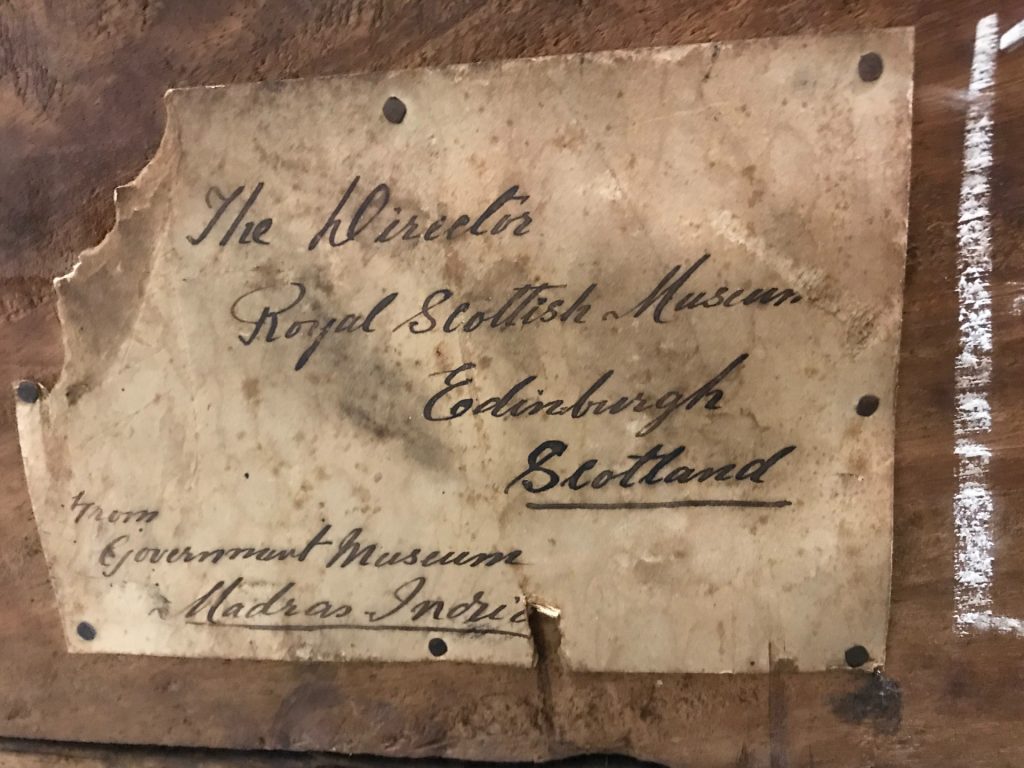

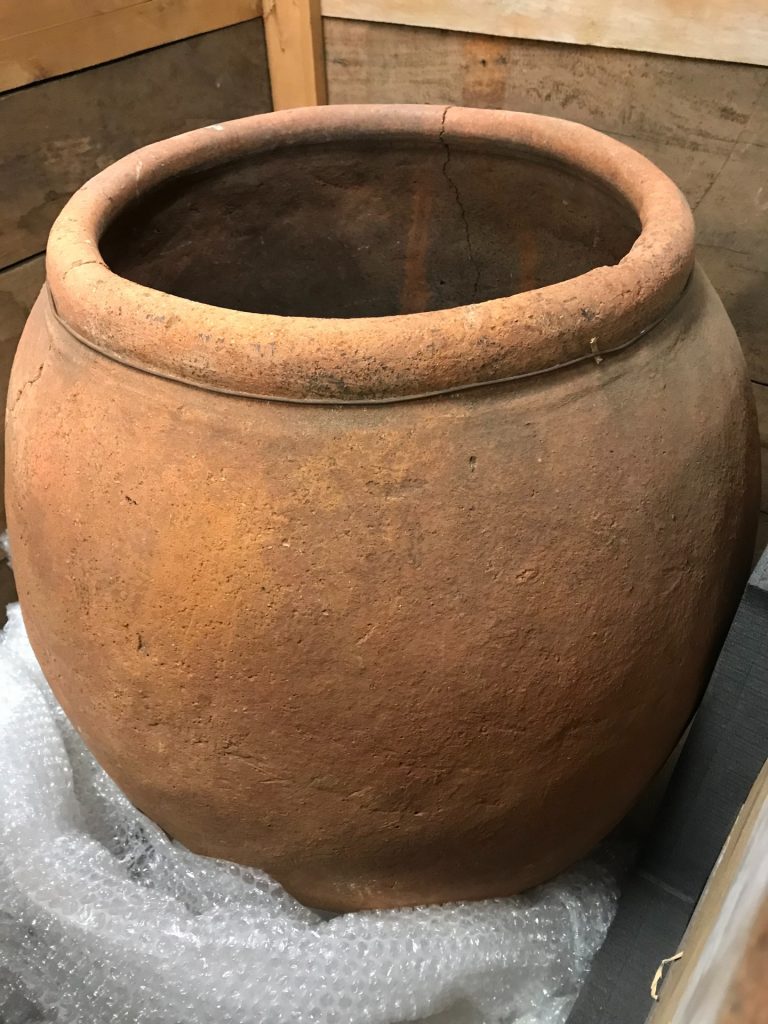

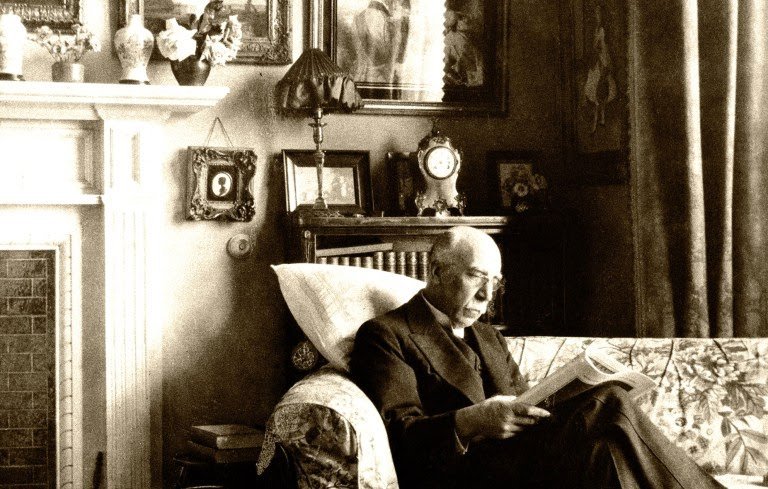

As we left the National Museums Collection Centre my eye was drawn into the shadows. At the back of a bay lay an old wooden crate, inscribed with an expressive cursive hand ‘THE DIRECTOR, Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, SCOTLAND’. The original label identified the content as a ‘Pottery Vessel, Ancient Indian, 1916.’ This was a thick red pottery urn, excavated by Dundonian Alexander Rea at the prehistoric cemetery at Adichanallur, Tinnevelly (Tirunelveli) between 1899 and 1905 and sent to Edinburgh by Scottish Zoologist John Robert Henderson, the Superintendent at the Government Museum at Madras (Chennai). I thought of my predecessor, Alexander Ormiston Curle, taking receipt of the object in wartime conditions. The temperature seemed to drop a little in the room and the hairs stood up on my neck. I adjusted my facemask, straightened my scarf and prepared to move out into the Autumn air. Time passes, of that we can be certain.

Original label

Pottery Vessel

Dr Chris Breward, Director

Alexander Ormiston Curle, former Director of Royal Scottish Museum, Chambers Street