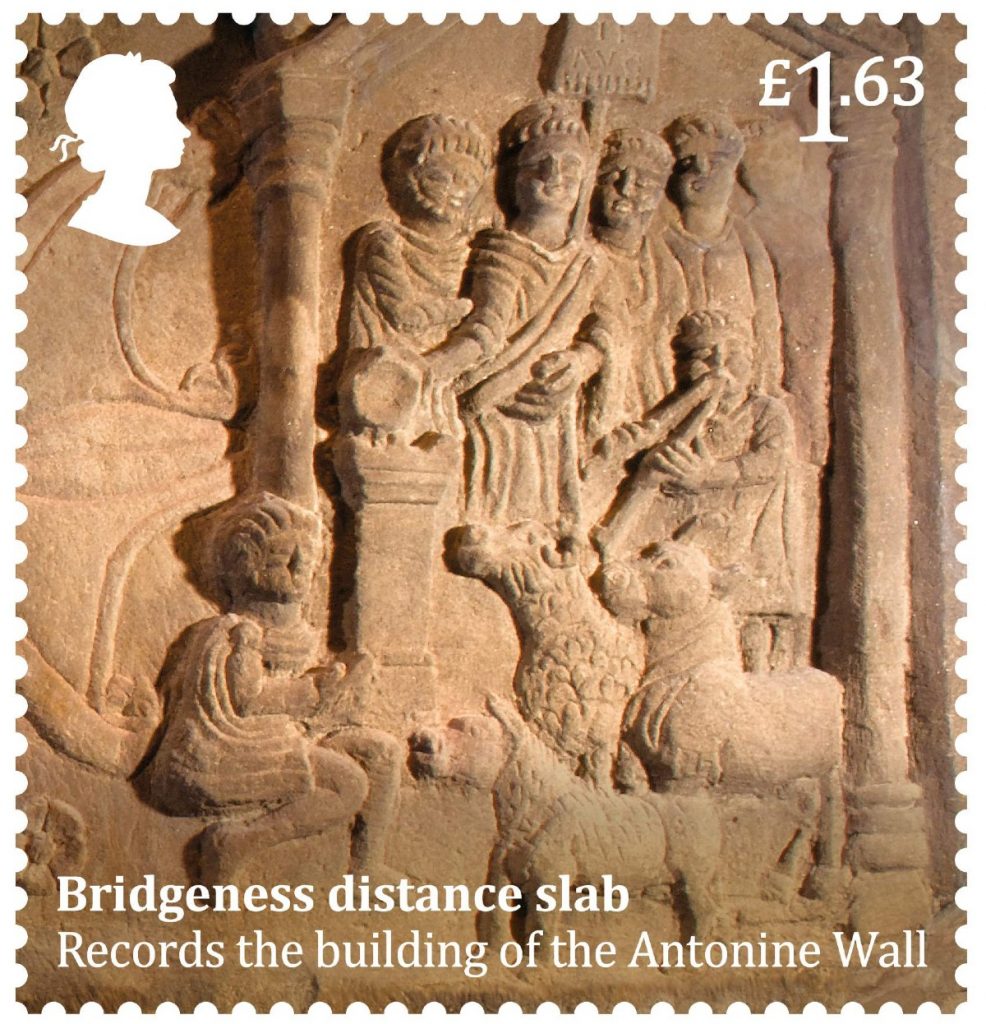

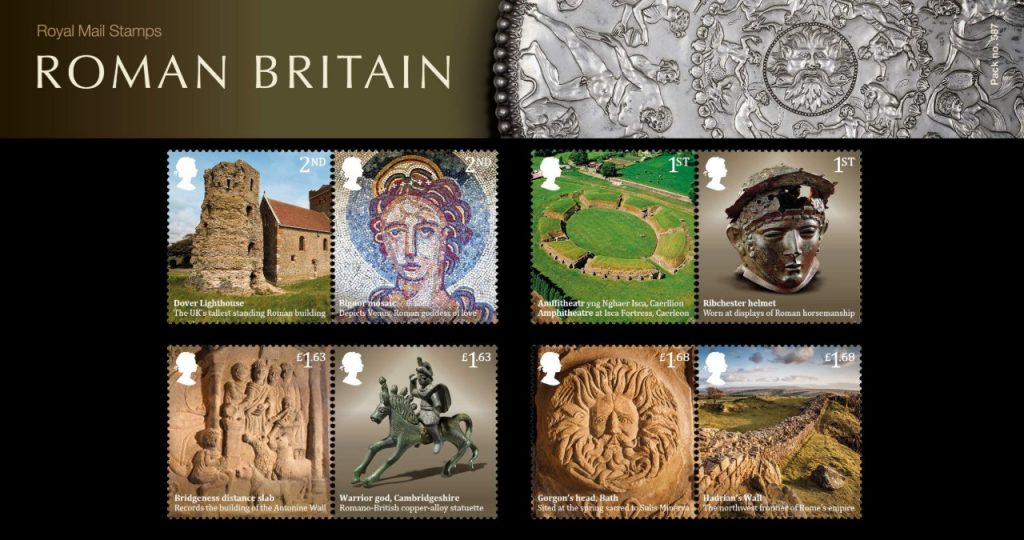

One of our most prized Roman artefacts has received the ultimate accolade – it’s featured on a Royal Mail stamp.

The Bridgeness distance slab is one of the finest Roman sculptures from Britain. It was carved almost 1900 years ago, around AD 142, to commemorate the building of the Antonine Wall, the Roman frontier that ran across Scotland from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. Bridgeness (now part of Bo’ness) lies at its eastern end. Stones commemorating the building of the Wall are known from all along its length – there’s a wonderful collection of them in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow – but this one, from the Wall’s end, was the most spectacular.

You can find more details about it elsewhere on our website, but in essence it’s a stone of three parts. The centre has an inscription in beautifully carved Latin, dedicating the work to the emperor, Antoninus Pius, and recording the building work down to the last pace – 4,652 of them, representing almost eight kilometres of wall and ditch. (A Roman pace was a double-step, five Roman feet or 1.66m.) This was a monument to the hard work of the soldiers; you can almost smell the sweat and hear the swearing in this carefully-counted tally.

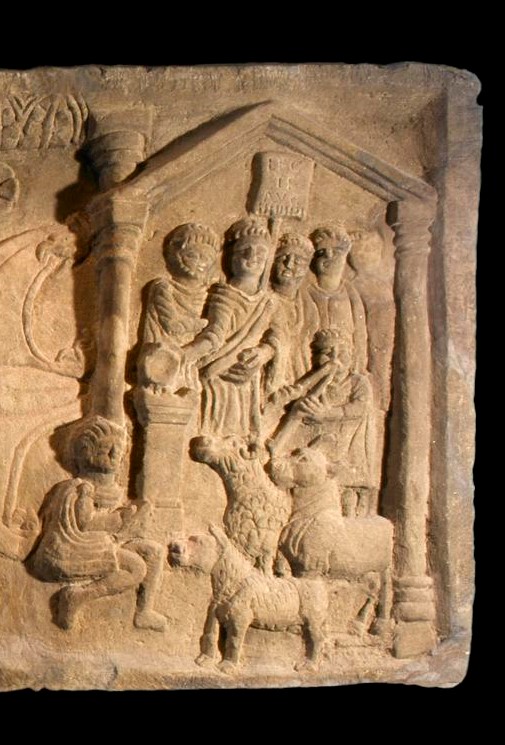

The stamp features the right-hand end of the stone. This shows a religious ceremony that took place before the Wall was built, and before the army started its campaign. In order to purify the troops for the task ahead, and to win the favour of the war-god Mars, a sacrifice was needed. This was known to the Romans as a suovetaurilia – the sacrifice of a pig, a ram and a bull to please the god. These poor beasts are shown at the front of this scene, with an attendant at the left who will carry out the bloody task, and one to the right playing pan-pipes to accompany the rite.

Behind the animals is a group of men. The one in front is probably the commander of the legion, who was A. Claudius Charax – a native of Pergamum in Turkey, a man of limited military experience but a personal friend of the emperor. He was given this job purely on merit, of course … The circular object in his right hand is a patera, a bronze or silver sacred vessel, from which he pours a libation onto an altar – you can see altars just like this in the Early People gallery of the museum. The group of soldiers behind him watch the solemn ceremony. One of them carries a flag bearing the legion’s title: LEG II AVG, the Second Legion Augusta. Their base was in Caerleon in south Wales, but most of them had been sent north for the campaign and the building works.

The left side of the stone has a scene of battle and bloodshed, with a Roman cavalry officer triumphing over the local ‘barbarians’. One is trampled underfoot, one speared in the back, one has been captured and beheaded, and the last one awaits his fate. It’s a brutal picture of frontier warfare, seen through the victor’s eyes. When the museum reopens you can inspect this scene in all its gruesome detail – too bloody to put on a stamp.

The Antonine Wall is now a World Heritage Site, one of only six in Scotland. This puts it on a par with the Taj Mahal or the Egyptian pyramids, emphasising just how important our Wall is. Its logo is this Roman cavalryman from the Bridgeness slab – but without the local victims, which rather sanitises the bloodshed and brutality of the Roman conquest.

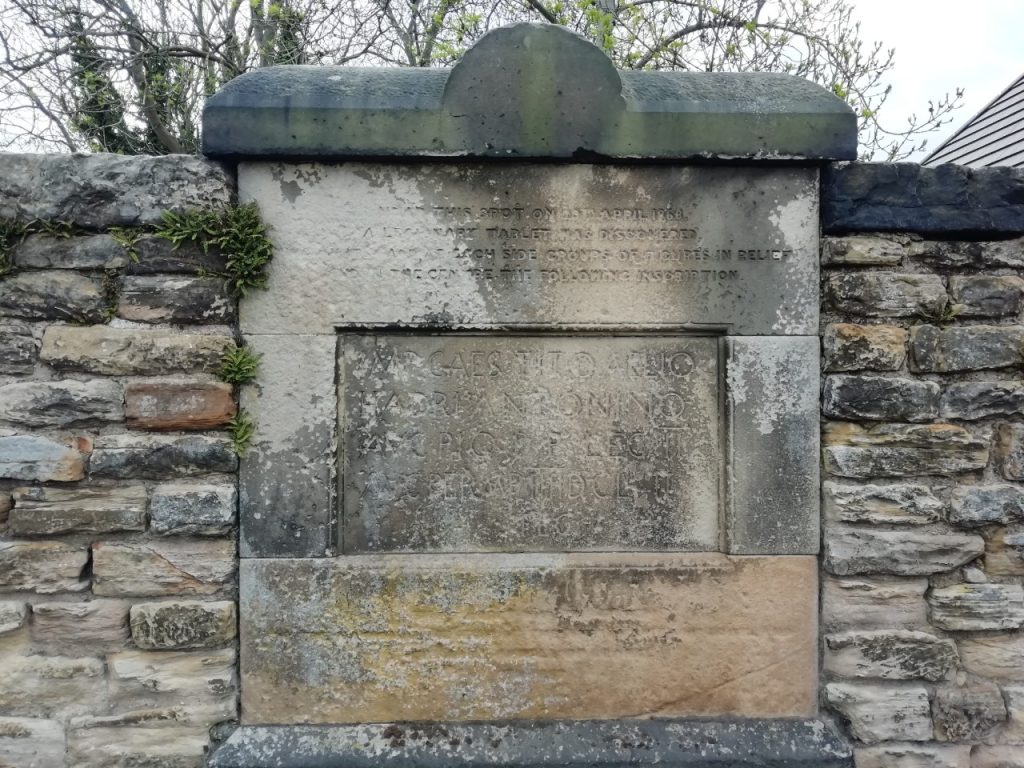

When the slab was found in 1868, a copy of the inscription was put up at the findspot as a condition of its donation to our museum. You can still see it today, though it’s pretty badly weathered after 150 years of fresh sea air.

Historic Environment Scotland are working with local councils all along the Wall to make this great monument better known to the public. They scanned our original stone, working long nights in the museum after the visitors had gone. This laser-generated model was used to carve an exact replica of the original.

Today it stands close to the findspot, marking the end of the Wall – maybe… If you want to start an argument among Romanists, ask them where the east end of the Antonine Wall was. Some believe it was at Bridgeness because the stone was found there. Others think it was a little further east, at Carriden, and argue that the stone was moved later. It’s also possible that the stone was never built into the Wall. Carriden is a lovely spot, but it sits on a bluff high above the sea. If you wanted your monument to be appreciated by those approaching from the water, perhaps Bridgeness was the more impressive place, on a promontory sticking out into the Forth.

The real stone is a bit misleading because it’s monochrome. Relying on the colour of the stone alone is like seeing the world in black and white. The Roman world was technicolour – the stone was just the canvas. When the slab was conserved in 1979, traces of red paint were noted in the lettering, which would have made the inscription much more visible. Red paint was also noticed on the cavalryman’s cloak and, rather brutally, on the head and neck of the decapitated barbarian.

New research led by Dr Louisa Campbell at Glasgow University has greatly extended this picture. Using a range of scientific techniques, she’s found traces of red and yellow paint on various parts of the stone, and suggested a vivid reconstruction of how the left-hand panel once looked. The colour brings the sculpture to life, in all its vibrancy and brutality. This was no mere piece of public art, but a triumphal celebration of Rome’s conquest on its northern frontier.

And now those conquests are memorialised on envelopes! The stamps bear images from across Roman Britain, from the northern frontier to the white cliffs of Dover. For a mere £1.63, the Bridgeness slab will continue to carry messages – though perhaps not quite how its makers intended.