Over the past couple of weeks I’ve been back into the Grand Gallery of the National Museum of Scotland a couple of times to make some short videos. Blessed by good weather these sessions have benefitted from the clearest beams of sunlight pouring through the glass, casting dramatic shadows from the ironwork across empty spaces, displays and objects, just waiting for their reawakening. ‘It’s like the final scene from the Sleeping Beauty’ I think as we film. Tchaikovsky should be playing in the background.

Yet, beautiful though those moments were, our museum lacked something. It lacked the presence of staff and visitors. Two decorators were methodically applying fresh paint to a radiator and one of my security colleagues engaged me in brief conversation about one of the cabinets that had attracted my attention. But otherwise all was still and silent. It brought home to me the importance of the connection between objects and people in making museums such compelling places to visit, and reminded me of the various times and circumstances in which such connections have enriched my own life, and I’m sure the lives of many others.

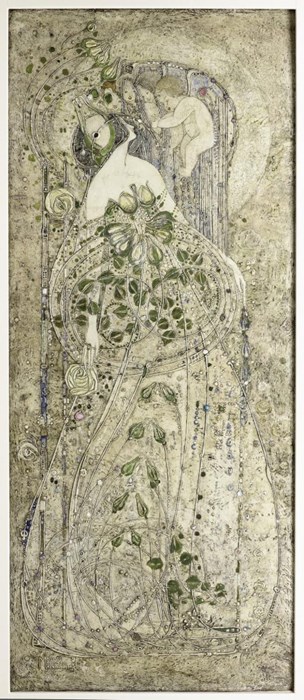

Back in 2009, when I was still working at the V&A, I visited Edinburgh with two colleagues to negotiate the loan of an architectural model of the Falkirk Wheel from RMJM’s offices for an exhibition we were preparing on British design to coincide with the London Olympics in 2012. We reserved time to visit the National Museum of Scotland so that we could learn more about design in Scotland and I’ve powerful memories of intense curatorial debate around the politics and aesthetics of making and display as we negotiated stairs and mezzanines. More recently I cannot pass by the delicate and ghostly gesso panel of ‘Summer’ by Margaret Macdonald without recalling those productive years in my life and that happy day away from the routine of the office. Museum exhibits are powerful mnemonics, prompting recall of unexpected discoveries and past conversations.

The experience of lockdown has conditioned many of us to engage with collections at a distance, through the rich digital content which museums like ours have made available for on-line learning, research and entertainment. In the old world of museums this function was delivered through the ‘study collection’ of object types in all their diverse but carefully ordered variations and sometimes through the box files of the picture library in which black and white photographs of an accessioned item along with relevant catalogue and provenance material were stored in brown cardboard folders. Whether experienced in the store or archive or in the more interactive and democratic multi-coloured media of the digital data era, the encounter with the object is generally solitary at first, but no less personal and intense than those in-gallery social interactions with surfaces, people and ideas. One find or click, spins off into another; networks of scholarship or communities of knowledge open up and overlap, new ideas are sparked.

As we move gradually from one mode of engagement to another and the physical museum prepares to open its doors to the public once more we enter a transitional phase where the connections between museum objects, visitors, staff and buildings almost hum and sing with anticipation of awakening. I must resist the temptation to literally kiss our objects alive when that day comes, but I hope you’ll join me in reconnecting with and celebrating the unique contribution museums make to human experience, connection and our understanding of the world, as I thank you for the valued support you’ve already given and I know you’ll continue to provide in the months and years ahead.