Since I began working as an Assistant Curator of Science six months ago, my main project has been working on an inventory of one of our stores at the National Museums Collections Centre. This is important because we need to know that we have a record, and an accurate location, for all of the items in our care.

This store houses many of the larger objects from the museum’s computing collections, the majority dating from around the 1950s-1980s. In some cases we have a lot of information about where individual machines came from and how they were used while they were still operational, but others are machines that have been found unregistered in the stores years after they first came into the museum.

This means that this inventory work isn’t a simple case of updating records to make sure that each item is described and located correctly, but also means undertaking research into the objects which appear not to have numbers or records.

This involves:

- Doing research into the collection itself in order to reconcile items with their records, where they have been separated from their numbers since first coming into the collection.

- Trying to match up individual parts of computers which have been separated as they have moved between our stores.

- Doing research into the unregistered computers to help make decisions about what we should do next with these items.

Over the course of this project, I’ve been lucky enough to work with, and do research into, many interesting computers from our collection. I wanted to share some of their stories, and the work that I’ve been doing to help improve this collection.

1. Powers Samas Tabulator, 65 column

Some of the earliest examples of computers in this store belong to our collection of Card Punch machines.

Punch cards were essentially a very early means for computers to store data, similar to the way in which computers now store files. All data for storage or for writing programmes needed to be input using these cards.

Punch card installations were typically made up of three machines, each doing a different part of the job. There was one machine that would punch the holes into the cards, a machine which sorted or collated the cards and finally a machine which read the data that had been punched into the cards.

Machines of this type were often used for business purposes, and from the 1930s onwards it wasn’t uncommon for offices to have a whole department of people involved in their operation and use.

There were periods in the past where large numbers of these machines came into the museum, and therefore were not registered at the time. A volunteer project was undertaken in 2017 to catalogue and photograph all of the punch card machines in the collection.

You can refer to this previous blog post on card punch machines here.

The information recorded about each of these machines has been invaluable in enabling us to make decisions about what to do with them. For example, in some cases we have duplicates, meaning that we need to make a decision about whether it might be better to transfer one example to another museum, giving more people access to it.

I recently accessioned one of these machines into the collection, meaning that we made a decision to permanently retain the object in order to help us tell the story of the development of computers within the UK.

2. Ferranti Mark 1

Following on from developments during the Second World War, there was increasing interest in attempts to develop a ‘universal digital computer’. However, this proved difficult to achieve, particularly because of the continuing lack of resolution to the problem of data storage. One particularly innovative method used to resolve this problem was the development of Cathode Ray Tubes for digital storage.

Making use of CRT stores, the Ferranti Mark 1* was developed as the result of a collaboration between Manchester University and Ferranti, and was considered to be the world’s first “stored program computer.” It also became the world’s first commercially available computer when it was installed at the University of Manchester in 1951.

In our collection, we have several parts of a Ferranti Mark 1*: a computer processor section; a computer drum unit; a computer fridge unit; and a logic door.

These parts almost certainly came from the one used by A V Roe & Co Ltd, an aircraft design company based in Manchester, where it would have been used for aircraft design calculations. After being used here, the computer passed to a technical college, and then to a museum. In 1975 it was “rediscovered”, and its worth realised.

It was actually being stored in a disused sewage pumping station, where it was found in very bad condition and covered in chicken droppings. Representatives from several different museums and organisations came together to view the computer. However, due to space constraints, no one single institution could commit to accepting the whole machine. Therefore, a decision was made that each would take some sections of the computer. That is how these parts came to be in our collection, and shows how museums often cooperate in order to preserve important objects!

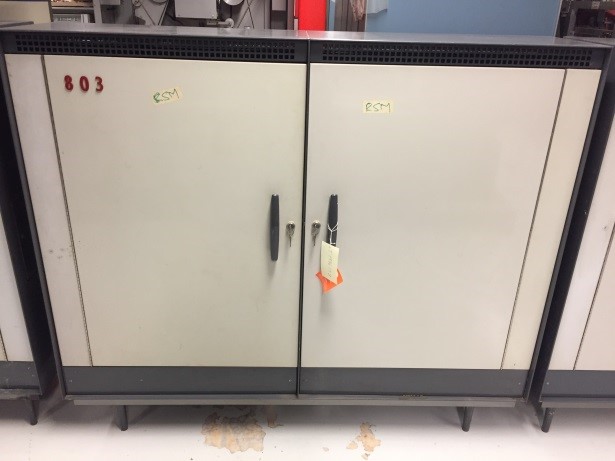

3. Elliott 803 Digital Compter

The Elliott 803 digital computer was in production from 1960, and was part of the company’s 800 series of computers. This computer was actually considered a “small” computer at the time, which gives you an idea of how large computers could be! Indeed, one of the reasons why it is so difficult to display items from this collection is due to the sheer size of computers from this period. The size can also make it difficult to document these collections.

Before I started work we had just one record for all the separate parts of this computer. This seems fine when all the parts are together, but what if they get moved! Having just one record means we can’t keep locations updated properly on our database, and we run the risk of losing track of where particular parts have gone. I worked with our systems team to create separate records for each individual part (T.1986.17.1, T.1986.17.2 etc.) which means that we can now keep their locations up to date.

4. ICT 1301

The ICT 1301 was produced from 1960, and first sold in 1962. It was made by International Computers and Tabulators (ICT), which was formed by the merging of Powers Samas and British Tabulating Machine Company in 1959.

The ICT 1301 was considered to be a business computer which was normally used for office work, and was particularly good at performing calculations. It was quite unusual at the time because it was based on decimal rather than binary logic. This meant that programmers didn’t have to learn binary arithmetic, and therefore it was more accessible for use in the everyday workplace.

One of the challenges of documenting the computing collection is that, due to the size of many of the complete units, parts of computers have been spread across various locations within the store, and it is sometimes very difficult to match them back up, meaning that it is often necessary to do detective work in store.

One example of this is the work that I’ve been doing to match up panels which have been removed from their computer. This involves trying to match up panels to computers according to their colour and measurements.

As can be seen from this photograph, this is quite a big undertaking!

![Our wall of mysterious panels…]](https://blog.nms.ac.uk/app/uploads/2019/09/Image-10-1024x463.jpg)

As shown in the image above, our ICT 1301 units are missing their panels, and by taking measurements, and finding catalogues for the computer online, I was able to match up the correct panels. This means that these panels can now be associated with the rest of the computer in our collections database and so we know exactly what belongs to this computer!

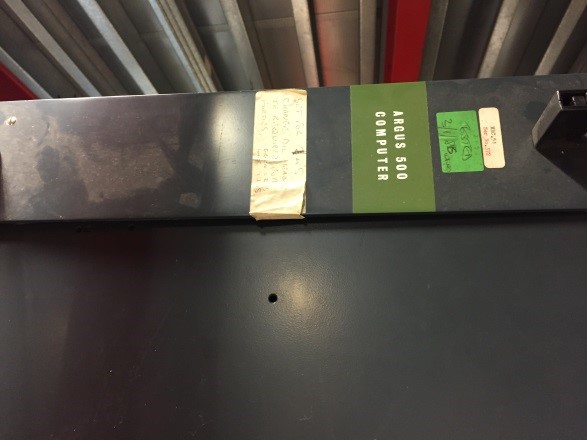

5. Ferranti Argus 500

We have several examples of Ferranti computers within the collection, including a Ferranti Argus 500. These were produced from 1964, and were used in a wide range of different industries.

When museums collect objects, it’s important to also collect information relating to them, so we can properly tell their stories. We have many object files, which contain interesting information about the items in our collection.

By using these object files, I learned that our Ferranti Argus 500 was part of an original off-shore telemetry station serving British Petroleum’s Forties Oil Field. This was the first to be developed in the North Sea, and produced oil which was then piped to the company’s refinery in Grangemouth.

In 1974, two Argus computers were installed in BP’s Field Control Centre in Dyce, Aberdeen. They were connected to pressure and flow measuring instruments on every platform, and at Cruden Bay and Grangemouth. This meant that operators in the control room could clearly see what was happening in each of these areas. This was important as it meant that swift action could be taken in the event that something stopped working. Information in the object files shows that, in the early years of their installation, the computers were prone to breakdowns, meaning that an engineer sometimes had to sleep alongside the machine, ensuring that if it broke down during the night the problem could be quickly resolved so that it wouldn’t disrupt the rest of the system.

The Argus was acquired by the museum in 1988, and letters from the time show that we weren’t able to acquire all parts of the computer due to space restrictions in the museum’s store. However, a selection was taken which would enable them to be reassembled to form a suite which would represent the complete machine. This information about what we actually acquired also proved helpful when trying to match parts of the computer which had been scattered in various locations throughout the store.

Hopefully this selection helps to illustrate the wide variety of objects within our computing collection and their interesting histories, as well as demonstrating the work that goes into maintaining this collection and making it more accessible and understandable!