2019 is a big year in engineering and industrial heritage. It marks two major anniversaries associated with one of Scotland’s most well-known inventors: James Watt. It is 250 years since he patented the separate condenser that vastly improved the efficiency of steam engines and it is 200 years since he died, on 25 August 1819, aged 83.

Writing in The Edinburgh Review in 1829, Scottish philosopher, Thomas Carlyle summed up the significance of efficient steam as he saw it at the time:

“We remove mountains, and make seas our smooth highway; nothing can resist us. We war with rude Nature; and, by our resistless engines, come off always victorious, and loaded with spoils.”

Thomas Carlyle, ‘A Mechanical Age’, Edinburgh Review, 1829

All of this, many would say, was thanks to James Watt.

Nearly 200 years after Carlyle was writing, we know that the consequences of this seeming human triumph over nature have been far from entirely positive, with industrialisation kickstarting the climate change that is now a dire threat to the planet.

German current affairs website, DW.com, recently published an article saying:

“When the Scottish engineer James Watt refined the steam engine in the late 18th century, setting off the process of industrialization, at first in Britain, no one knew that this was also the start of human-caused climate change. Since then, we have been pumping ever greater quantities of carbon dioxide into the air.”

Patrick Grosse, DW.com, 4 August 2019

There is no denying that, whatever way you look at it, James Watt’s legacy has profoundly changed the world. This year there are events taking place all over Scotland, the UK and beyond to celebrate, commemorate, discuss and debate Watt’s life and work. The anniversary year and the lead up to it have focused attention on the man and his legacy and have seen new publications and exhibitions as well as workshops, conferences and performances. You can read about what has been happening in Scotland at https://jameswatt.scot/.

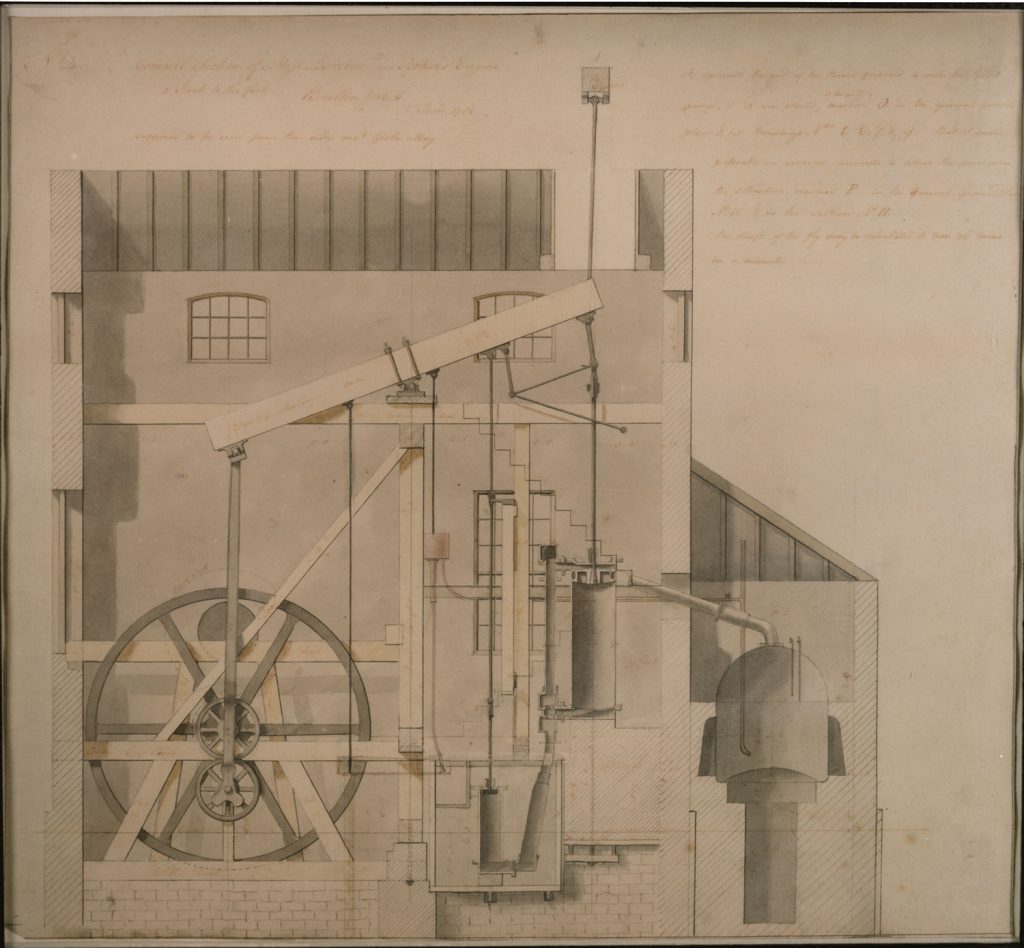

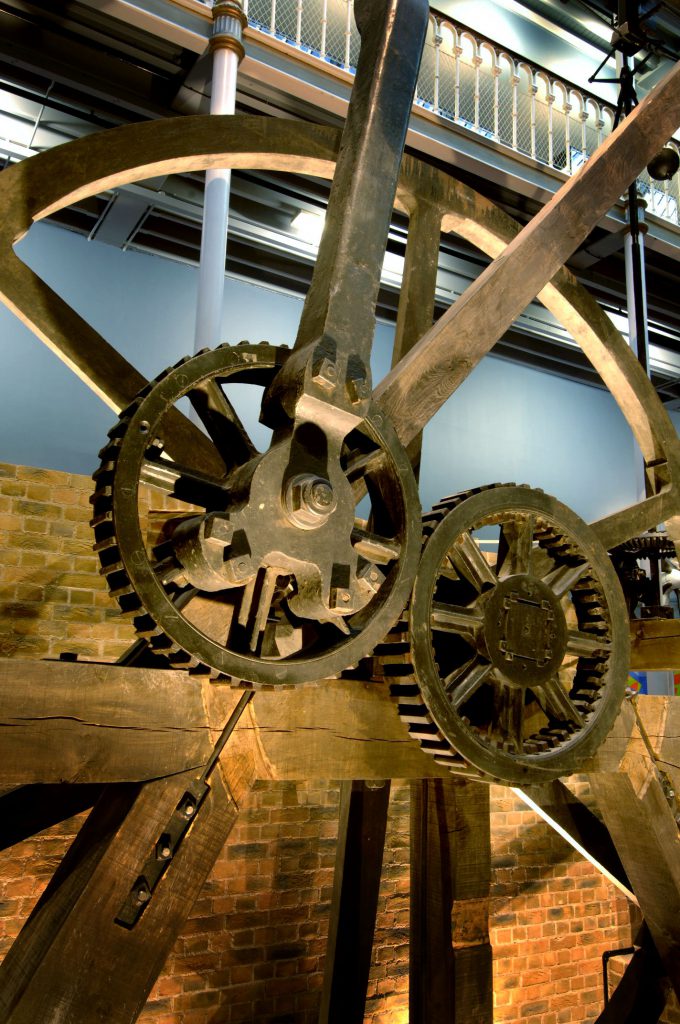

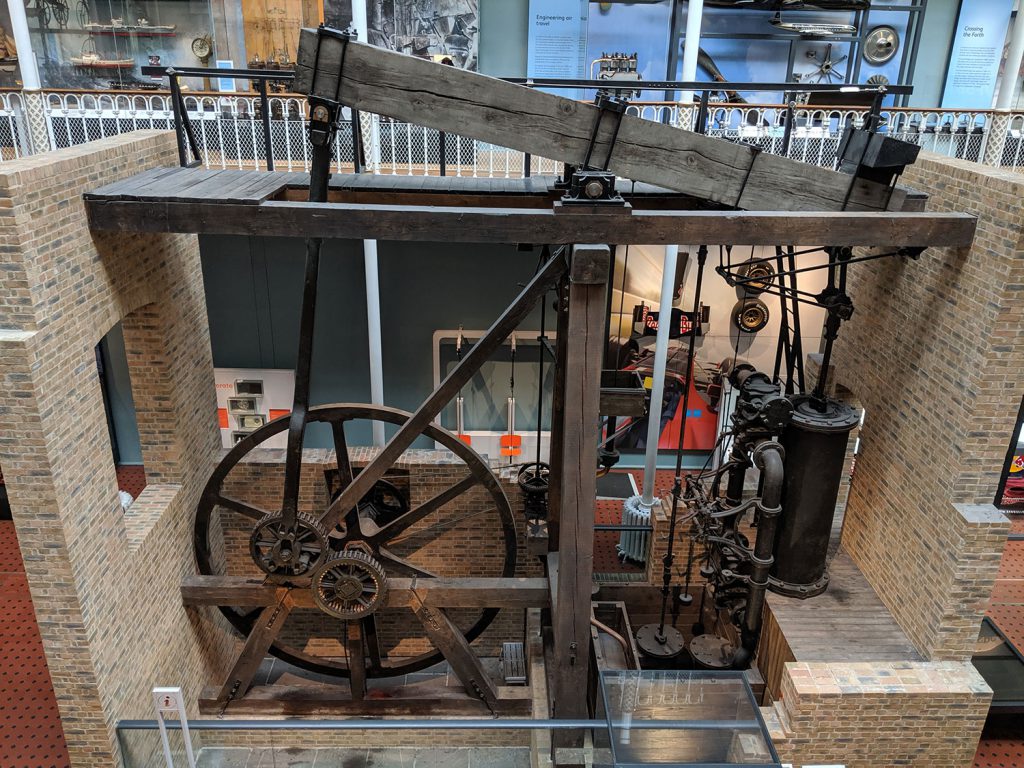

You can see Watt’s improvements to the steam engine by visiting the Explore gallery on Level 1 of the National Museum of Scotland. Here you will find the enormous Barclay and Perkins Brewery Engine that was built by Boulton and Watt in 1786 and operated at the Brewery for almost ninety years. It was one of the first engines to use Watt’s “sun and planet” gear which enabled the rotary motion of the flywheel. It consisted of a pair of cogwheels linked together, one running around the other, like the earth orbiting the sun.

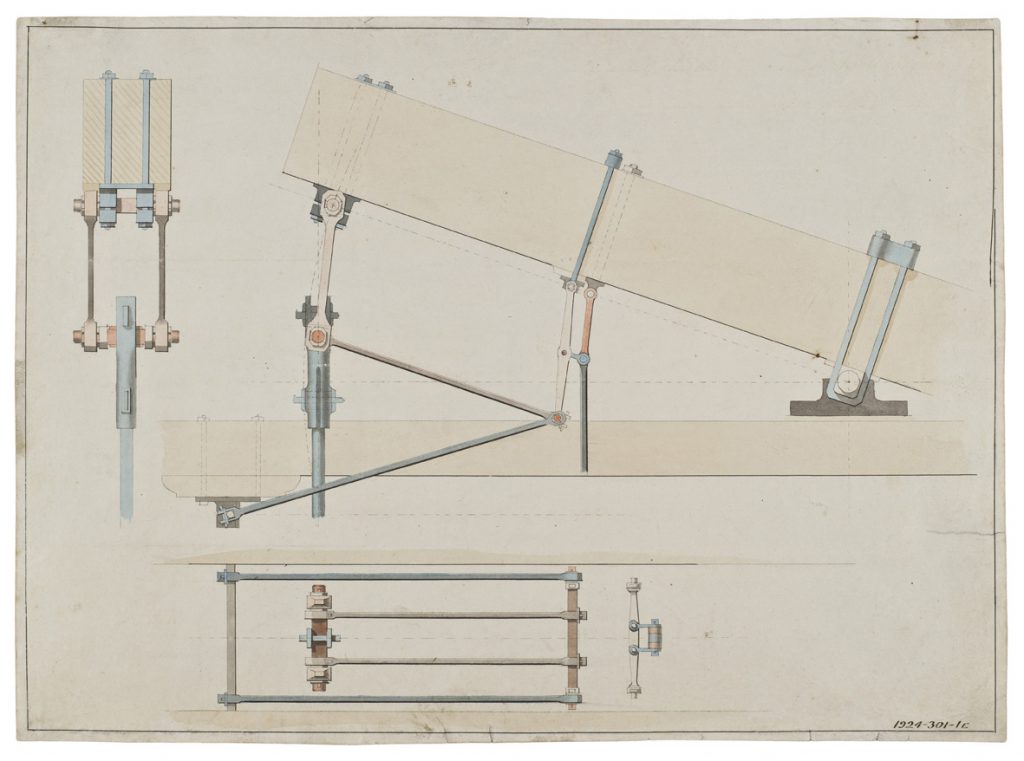

When first installed at the brewery, this engine was single-acting but Watt had patented a double-acting engine in 1782 and the Barclay and Perkins engine was converted to be double-acting in 1796. This made it operate more smoothly and capable of driving machinery as well as pumping water. It was also fitted with a “parallel motion” which allowed the piston rod to push as well as pull the beam. Reportedly, this was one of Watt’s favourite inventions. It enabled this engine to grind barley as well as pump water.

And, of course, this engine features the famous separate condenser, celebrated as Watt’s most significant innovation. Before the separate condenser, steam was condensed in an engine’s cylinder, which was inefficient. Through his experiments, Watt realised that the inefficiency was due to the repeated heating and cooling of the cylinder to condense the steam. His solution was the separate condenser. He recognised the need to keep the cylinder hot at all times and to lead the steam away into a separate condenser which would be permanently cold. Engines with separate condensers were three to four times more efficient than those without.

Of course, James Watt is remembered for far more than his improvements to steam engines. He was an engineer, an inventor and a maker of scientific instruments, and the collections at National Museums Scotland reflect all of these aspects. In the Discoveries gallery in the National Museum of Scotland you can see the only surviving signed instrument made by Watt in his Glasgow workshop, which was funded by the eminent Scottish chemist and Watt’s friend, Joseph Black. It is a cistern tube barometer made around 1760.

It was during his time as an instrument maker for the University of Glasgow, and through contact with academics and scientists like Black and John Robison, that Watt first started experimenting with steam and contemplating the inefficiencies of steam engines.

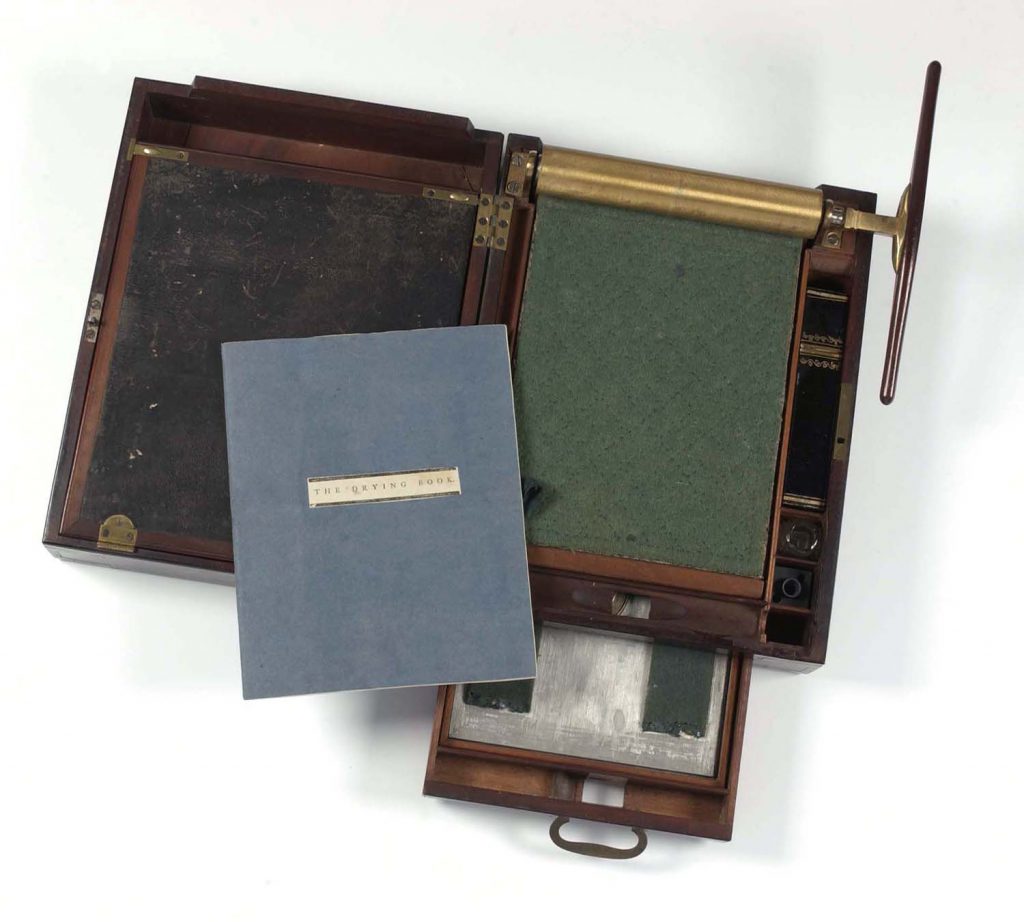

It might surprise you to know that, in 1780, James Watt patented what could be considered a precursor to the modern photocopier. He was growing frustrated with the tedium of having to make copies of letters by hand and was worried about the security of paying someone to copy sensitive letters and plans, so devised a way to copy letters onto thin paper using pressure. The letter-copy press was one of the first things that Boulton and Watt manufactured in partnership together. The company continued to produce the presses until long after Watt’s death and the principles behind it were used in offices up until the invention of the photocopier as we know it today. You can view a Watt copying machine in the National Museum of Scotland in the Innovators gallery.

Alongside the copying machine in Innovators is a display of medals, all of which commemorate Watt’s life and his achievements, emphasising what an important figure he is in the history of engineering, innovation and industry. This is also reflected in the number of places and institutions that use his name, such as Heriot-Watt University, and most of all in the many legacies his work left that have helped to advance the modern world.

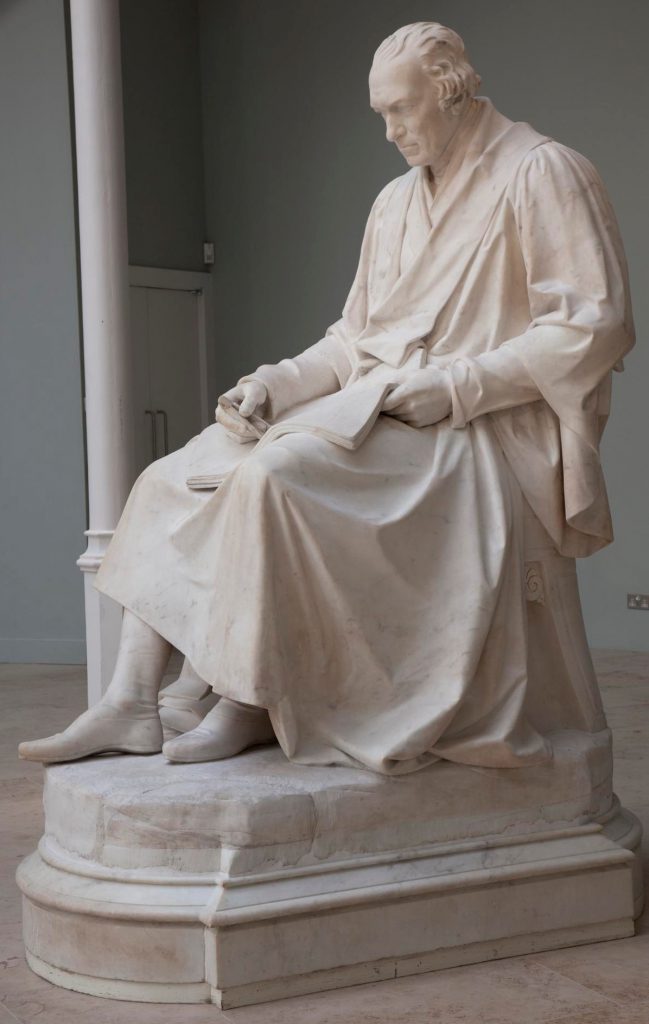

Statue of James Watt by Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey, on loan from Heriot-Watt University Museum and Archive.

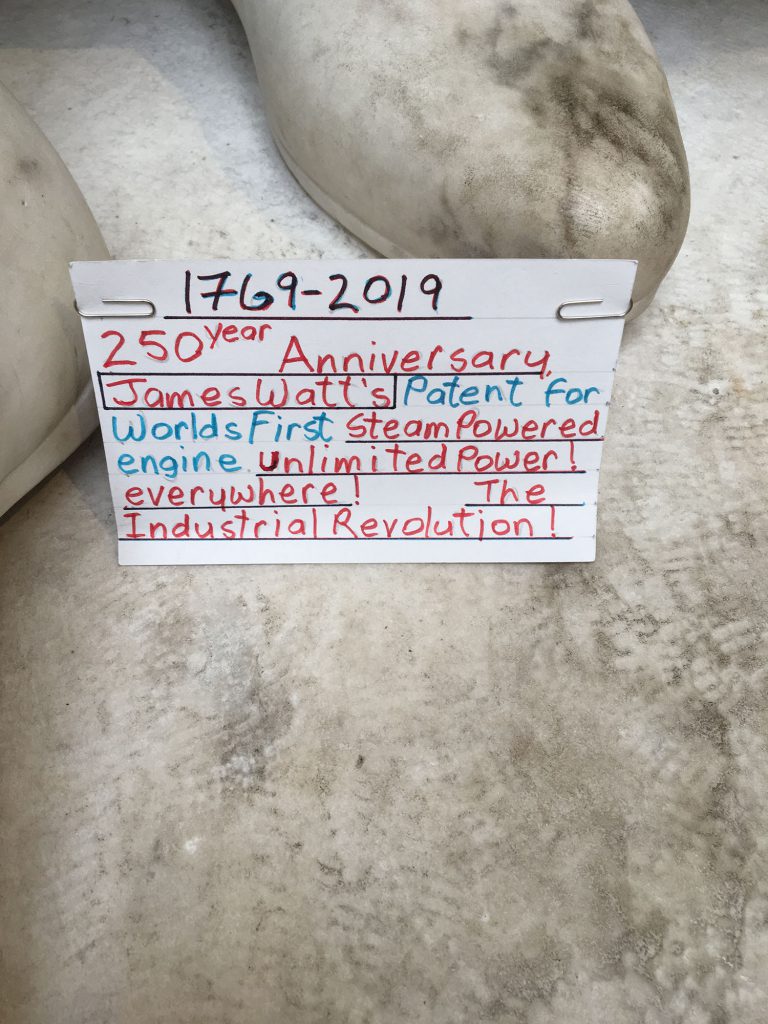

Note left on James Watt’s statue earlier in 2019. It reads: “1769 – 2019. 250th Anniversary James Watt’s Patent for World’s First Steam Powered engine. Unlimited power! Everywhere! The Industrial Revolution!”

If you would like to see what the man himself looked like, you can also visit the marble statue of James Watt, on display in the Grand Gallery in the National Museum of Scotland. The statue, by English sculptor Sir Francis Legatt Chantrey, is on loan from Heriot-Watt University Museum and Archive. Back in April this year a visitor helped us to celebrate the anniversary of Watt’s famous patent by placing their own label at his feet, showing that Watt and his achievements still have a place in the hearts and minds of many people today.