It is perhaps surprising to discover that 3D photographs were among the most popular souvenirs taken home by Victorian tourists visiting Scotland! Small, lightweight and affordable, similar to the ubiquitous postcard (which would only be introduced some fifty years later), these stereoviews were sold widely in shops, stations, cathedrals, hotels and even on boats.

A craze for 3D images swept the nation during the 1850s. By 1860, virtually every middle-class home in Britain had a stereoscope to view 3D stereoviews, which had become the best-selling format of photograph. The technology was developed in Scotland 170 years ago and is essentially identical to that used in today’s virtual reality headsets.

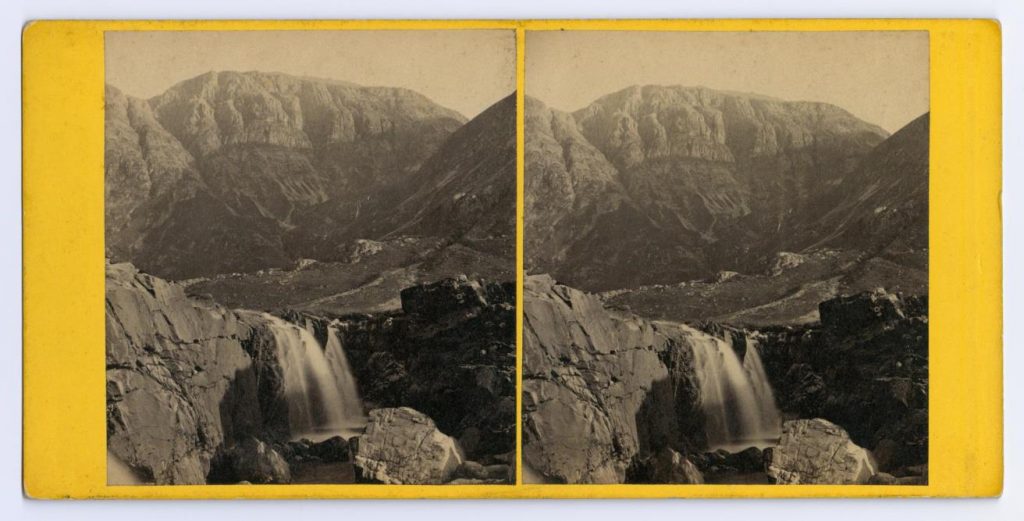

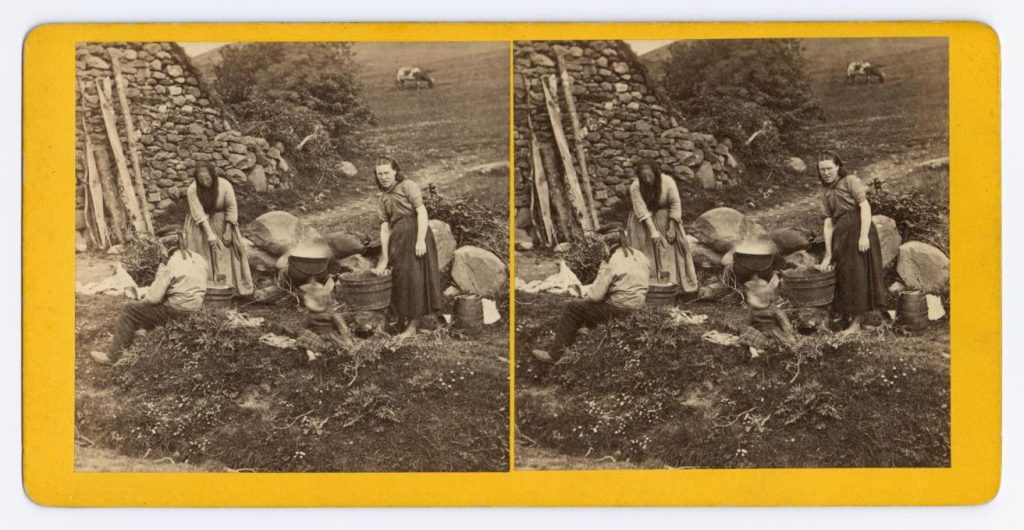

Looking at the side-by-side photograph above, it is difficult to perceive the slight differences between the two images that create the 3D effect. These differences become obvious when we oscillate between the two images.

Stereopsis, the science of binocular vision, was first described by Sir Charles Wheatstone in the 1830s. He invented a cumbersome table-top instrument, christened the stereoscope, which used mirrors to demonstrate his theory that each eye sees a slightly different two-dimensional picture of the world and the brain recombines the two images to create a perception of 3D space. Initially Wheatstone used simple drawings, but the invention of photography in 1839 revolutionised the potential of the stereoscope.

In Scotland, St Andrews was the cradle of photography, nurtured by the passion of Sir David Brewster, the principal of the University. Brewster had previously invented the kaleidoscope and recognised that there was huge public demand for special optical effects and entertainments. In 1848, he demonstrated his version of the stereoscope to his friends. It was a simple, compact, hand-held device which used lenses, rather than mirrors, to view two side-by-side photographs, which were obtained by moving the camera a few inches laterally between shots. Later, stereo-cameras would be developed with two lenses spaced about the same distance apart as our eyes, which took the side-by-side photos simultaneously.

Brewster’s stereoscope was first displayed to a wide public at the London Great Exhibition of 1851. Legend has it that Queen Victoria was delighted with the 3D effect and the stereoscopic craze was born. By 1856, Brewster reported that 500,000 of his stereoscopes had been sold!

Back then, travel was expensive and time-consuming, but through the stereoscope Victorians could instantaneously traverse the globe, visiting distant exotic locations, or even just bonnie Scotland. The extraordinary 3D effect provides a sense of immersion and participation in the picture – a real sense of being there. Little wonder that stereoviews became such popular souvenirs, as they provided the traveller with the facility to revisit their favourite spots.

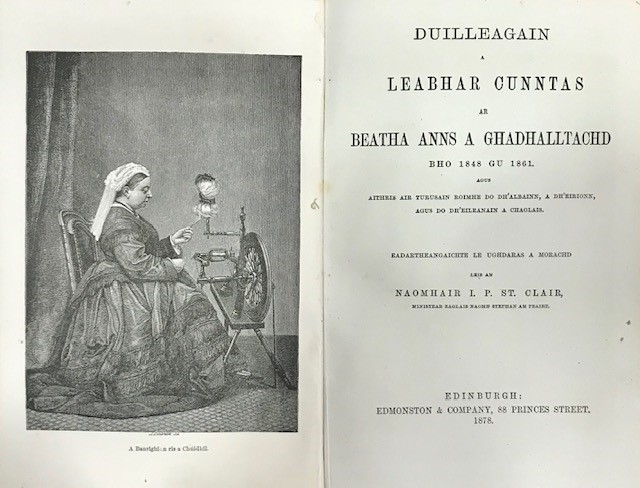

The skilled Aberdeen photographer George Washington Wilson took over 2000 stereoviews of Scotland and became the benchmark against which other stereo-photographers were measured. His photographs (in the form of etchings) were used by Queen Victoria to illustrate the places she had visited in her best-seller “Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the Highlands”.

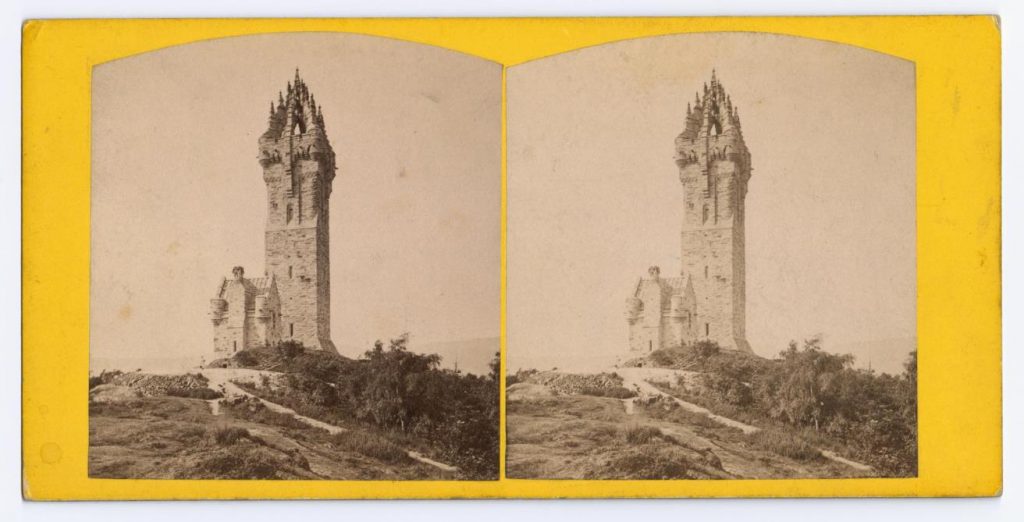

Over 200 Scottish stereo-photographers have been identified; among the most well-known are James Valentine of Dundee, John Moffat, Alexander McGlashon and Archibald Burns of Edinburgh, Alexander Crowe of Stirling and Thomas Rodger of St Andrews.

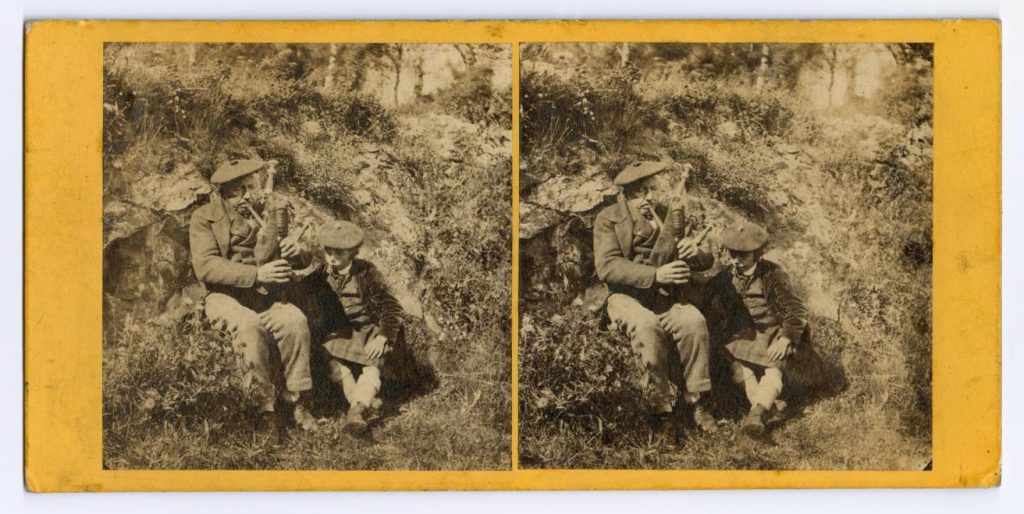

The stereoscopic photographic record of Scotland typically does not stray far from the tourist trail. These were the images that the public wanted to purchase. The photographers had a formula. As souvenirs, the images had to be taken from viewpoints that tourists had witnessed for themselves, or to recall locations mentioned by Sir Walter Scott or Queen Victoria, or be associated with Scottish heroes like William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, Mary Queen of Scots and Burns, or to be representative, or at least thought to be representative, of typical Scottish scenes.

In general, the photographs reinforce the stereo-typical “Wild and Majestic” romantic perception of castle-strewn mountains and lochs, populated by hardy Highlanders and tartan-bedecked bagpipers. The huge popularity of 3D images spread this vision far beyond our shores and stereoviews became yet another key building-block in the enduring myth of Scotland.

You can find out more about Victorian photography on the National Museums Scotland website.

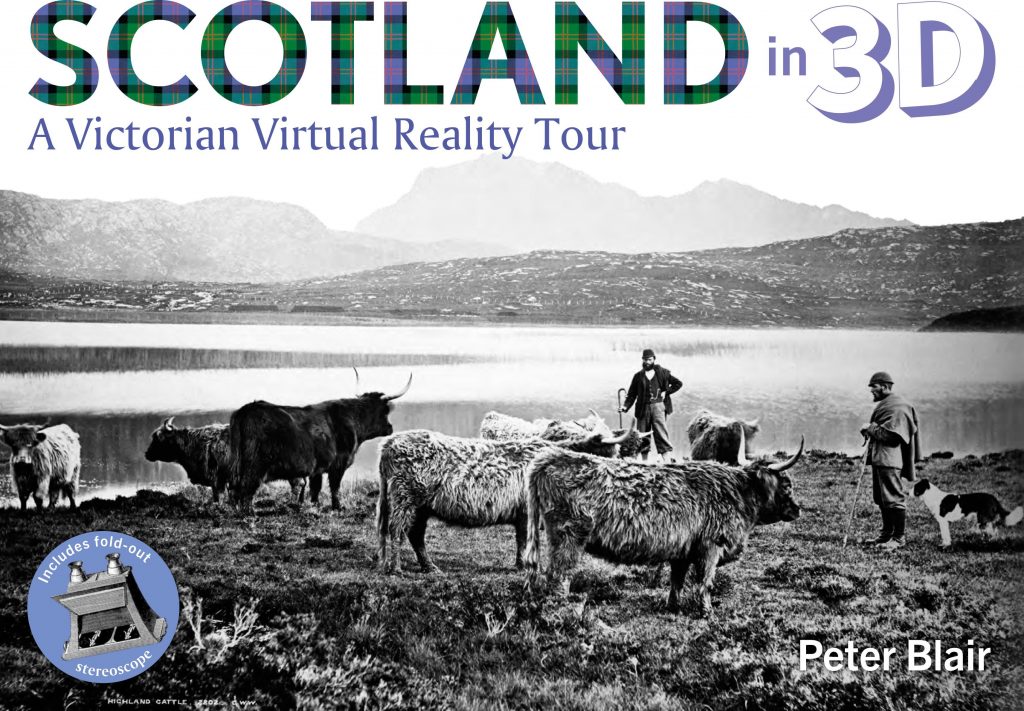

The amazing legacy of these early photographers is the subject of a new book Scotland in 3D – A Victorian Virtual Reality Tour, which is for sale in the National Museum of Scotland shop. The book includes a fold-out stereoscope which enables the reader to immerse themselves in the beauty of “Wild and Majestic” Scotland.

Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland is open at the National Museum of Scotland from 26 June – 10 November 2019.