Being a curator has its advantages. Not only can we indulge our obsessive-compulsive organising of millions of specimens, but occasionally we have a chance to enhance and develop the collection, going into the field and gathering more specimens. My speciality is dipterology (study of flies), which is why I can often be found sweeping my net in a forest while my friends enjoy a day at the beach.

In December 2018 I attended the 9th International Congress of Dipterology in Windhoek, Namibia. Travelling in another hemisphere is a fascinating opportunity to see and collect new insects. As beautiful as Namibian landscapes are, however, the desert is not the place to find the flies I am particularly interested in. Fungus gnats (Diptera: Sciaroidea) mostly inhabit forests and moors, enjoying a dark and moist environment.

Their larvae are often associated with fungi, hence the name, but they can live in rotting wood, bird nests or even as parasites of terrestrial flatworms. That is why Tsitsikamma, the largest remaining patch of indigenous Afromontane forest in South Africa, is the best place to look for them.

A series of mountain ridges shields the Tsitsikamma plateau from hot winds from Karoo and creates a unique microclimate with cool moist winters and warm moist summers. Tsitsikamma forest is a part of the Garden Route National Park, one of the most popular tourist destinations in South Africa. It is of vital importance to minimise the damaging effects of human activity and make sure that tourism, industrial forestry, and agriculture do not destroy this unique ecosystem.

Flies, like many insects, are an important tool for gauging ecosystem health. They are dependent on many other species and environmental conditions that create a perfect microhabitat; therefore they are the first to disappear as a response to any disturbance. The more diversity of insects we have, the more pristine an ecosystem. But to use this biodiversity assessment tool, we have to know exactly what lives in the area of study.

African flies are extremely understudied. Indeed, we know of more fungus gnats from the British Isles (542 species) than from the whole of Africa (437 species), although the continent is almost one hundred times larger than the British Isles. This means we could expect that at least a couple of thousand Afrotropical species of fungus gnats are still unknown. Too many new species to find and to describe and name!

There are many different methods of collecting flies; perhaps the best is a Malaise trap. Everyone who enjoys camping and has accidentally left a tent flap open knows how quickly the tent will become full of insects. Malaise traps work on the same principle: insects fly into a tent-like structure and are tunnelled into a collecting jar.

Another favourite method is sweeping with an insect net on vegetation, or anywhere where insects can fly or rest. When the net is full, flies have to be quickly and carefully picked up with an aspirator, or pooter.

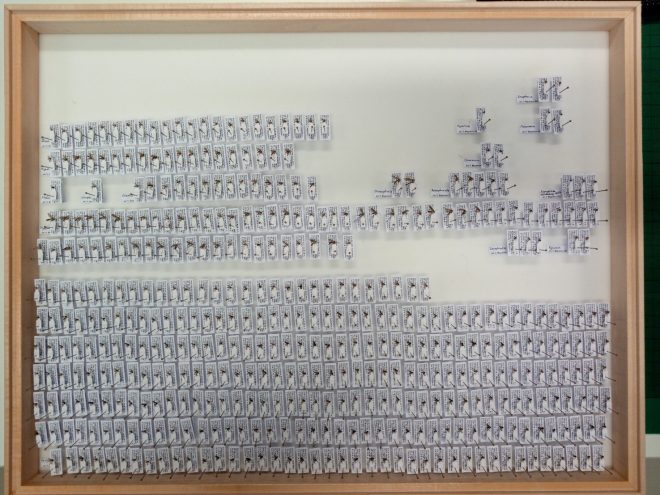

The most important part of collecting is documentation: we have to take photographs and film if necessary and record where and when insects were collected, what their habitat was like, which plants they were associated with and anything else that might be useful. In the evening, the day’s catch must be processed immediately. Insects have to be sorted and mounted (pinned or glued on small card triangles) or preserved in alcohol, or even liquid nitrogen, before they dry and shrivel. If the day was very successful, mounting can last well past midnight. So, when someone tells me how they envy my travels to exotic locations, I always respond that I envy their eight hours’ sleep!

But it is worth it. We found a lot of interesting flies, including Allodiopsis, a genus of fungus gnat never before reported from Africa, and a lot of specimens belonged to genus Phronia. Larvae of these flies feed on moulds and build conical shields of their excrements to avoid predators.

Furthermore, when I returned to Edinburgh and started sorting my catch, I was very excited to find that one seemingly ordinary-looking gnat turned out to be none other than Aynaphleba stuckenbergi. Brian Stuckenberg, a famous South African dipterist, collected one specimen in 1964. It was described ten years later and named after the finder. The only specimen is in a very poor condition, with just a wing and partial body preserved. Fifty-five years later we found three more specimens. Asynaphleba demonstrates some very primitive features, not found in fungus gnats since the Mesozoic, around 100 million years ago. Studying it may help to understand the evolution of this group.

One of the most remarkable finds was a specimen of a very rare fly – Vermileonidae, or worm-lions. Only two specimens of Vermipardus brinki were known before, and both are in the Natal Museum in Pietermaritzburg. Larvae of worm lions, just like antlions, build pit traps in sand and prey on the small insects which fall into them so the beautiful sand beaches of Nature’s Valley are the perfect habitat.

Now I am back in the office, sorting and identifying flies, destined for our collection and the collection of Natal Museum. Already three new species have been found and undoubtedly, there will be more. Describing and naming these new species will take a few months, and then I hope to return to South Africa. Too many flies, too little time!

If you’d like to know more about flies, follow our Twitter account @NatSciNMS and search for #YearOfTheFly and #FlyFriday.