One of my favourite things about working in a museum is the variety of objects I encounter. The Hunterian hired me to help move geological material as part of a larger migration to new facilities at Kelvin Hall, but in the last couple of years I have branched out to work with objects as diverse as taxidermy, fossils, scientific instruments, art on paper and, my favourite, multifarious things in jars.

Much of this new experience was quite outside my prior training with biological material; thankfully National Museums Scotland’s National Training Programme offers several workshops eminently suited to expanding a museum professional’s skillset. Earlier this year I attended two of them, one on Object Handling and a combined session on Integrated Pest Management and Object Labelling.

The Pest Management workshop advocated a holistic approach, recognising that everything that enters a museum, from clothing to packed lunches, is a potential vector for pests. The new store at Kelvin Hall contains a wide variety of collections so environmental conditions have to be carefully balanced and we need to be mindful of packing materials which may present a haven for pests.

Putting what I learned into practice, my first step was to reduce my use of acid-free tissue paper as a packing material. It’s a versatile, useful material, but prone to forming cavities that can act as reservoirs for pests. Instead I have started shaping custom holders and supports out of Plastazote (a closed cell polyethylene foam), which carries the added benefit of better immobilising the objects. Additionally, most of the shelves in the new store are mobile, so it was important to ensure that the objects on them don’t rock or move at all. The Object Handling workshop also covered how objects are moved and stored, which helped me see the specific challenges of moving racks and packing fragile objects.

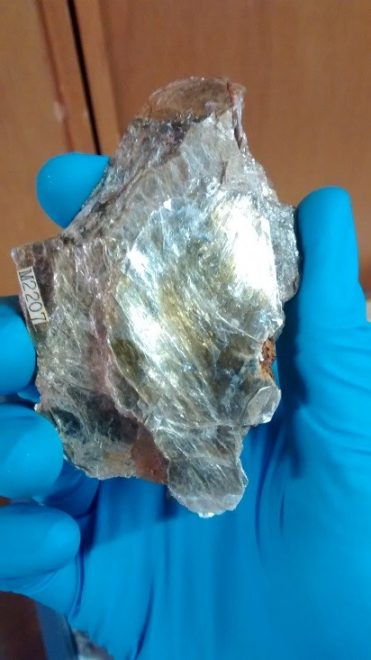

Ideally, an object should be touched as little as possible, including by its surroundings. It should also rest in such a way that no one part of it bears more weight than it can stand. For fossils, often awkwardly shaped, this can be tricky to achieve. In addition, these fossils are migrating from stationary cabinets to mobile shelves, and need to be more carefully packed as a result. The vertebrae seen above are kept in closer company than I might otherwise wish, but we try to prevent specimens being split between multiple storage locations. As I learned in the Object Labelling session, loss of data is a decay of sorts, deteriorating an object’s value, scientific, cultural, financial or otherwise. The difficulty in matching original labels to specimens is only compounded when they are stored across multiple boxes, drawers or shelves. Destruction of labels (and subsequent devaluation of objects) is also another method by which pests threaten collections. A mouse might not eat a fossil, but it might well shred paper labels.

The standard procedures of The Hunterian were put into place long before my arrival, so I was already familiar with some aspects of best practice in labelling objects. While I might know how best to tie a label onto a fox, before these workshops I had no experience with clothing, jewellery, paintings, furniture or the like. It’s fair to say that I have still not been called upon to sew a label onto a specimen (neither feathers nor fossils take kindly to it), but I have put some of the relevant techniques into practice elsewhere.

Prior to the Object Handling workshop I had never considered using pins outside entomology collections. When objects are too small and fragile for ordinary methods, pins can provide a more delicate, adjustable storage environment. In a similar vein, I had no idea that Paraloid (an acrylic resin) could be used as a substrate for ink labels. Previously I had only seen it used as a combined adhesive/waterproofing agent for printed labels. Writing on Paraloid on the surface of an object holds several advantages, among them making it much more difficult to lose the label!

I won’t recount all of the principles of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) we covered in the workshop. Briefly, it promotes a research and vigilance-based approach to pest control. Control is the operative word as eradication is often more difficult, expensive and dangerous than feasible. IPM requires, for example, understanding the life cycles of pests, so that their numbers can be predicted and a seasonal lull is not mistaken for successful elimination. Emphasis is placed on everyday preparation rather than treatment (“an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure”) and a comprehensive monitoring regimen to allow for regular updates in policy. In other words, the most important task for me, as far as pest control is concerned, is to keep my workspace clean! I have also taken to picking out old, desiccated remains of previous visitors (I haven’t found any evidence of current or historic breeding populations) and taking them to the curator of entomology, so we can keep a record of what might crop up in future. Unfortunately my camera isn’t equipped to capture such tiny specimens.

I was grateful for the opportunity to attend these workshops and will be implementing what I learned there for some time to come.

You can find me, infrequently, on Twitter: @TheRargian.