Fieldwork for the Military Collections and the British Empire research project (AH/P006752/1) has gathered pace since the beginning of 2018 and I have had the opportunity to examine a number of fascinating collections, including our own at National Museums Scotland, and at our principal project partner, the National Army Museum.

The range and types of artefacts that can be found in military collections is impressive: from arms and armour and enemy standards, through to personal ornamentation and domestic items. Some defy singular categorisations and further research into their stories demonstrates the complexities of colonial encounters.

Through my research it has become clear that members of the British Army were creators and collectors of commemorative objects. These commemorative pieces – which sometimes deserve the designation of ‘relics’ – act as poignant reminders of the devastating and bloody costs of military conquest and Empire.

Cawnpore (Kanpur) and the Indian Uprising

One of the conflicts of the 19th century that features in the military collections I have examined thus far is the Indian Uprising (known at the time as the Indian Mutiny) of 1857-8. The object that is the focus of this particular post – the Cawnpore Cross – exemplifies a British perspective on a conflict that both then and now is remembered differently in India. The lasting significance of this colonial conflict is encapsulated in its shifting designation as a ‘Mutiny’, ‘Rebellion’ and ‘Uprising’.

As historians have identified, the Indian Uprising was caused by a multitude of long and short-term factors that fostered discontent against British East India Company rule. One of these short-term factors involved the rumour that cartridges for the new Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle were greased with pig and cow fat, triggering anxiety amongst Muslim and Hindu soldiers in the British Indian Army that they were being encouraged to transgress their religious observances, and that this was part of a strategic desire on the part of the British to convert them to Christianity.

Upon the outbreak of the conflict, one of the Scottish infantry regiments enlisted to supress the Uprising was the 42nd Regiment of Foot (later known as the Black Watch). Under the command of Sir Colin Campbell, the 42nd marched to relieve Cawnpore (now Kanpur), one of the main areas of revolt, in April 1857.

At Cawnpore, the main figurehead of the Uprising was Nana Govind Dhondu Pant, known to the British as Nana Sahib (1824-?). Nana Sahib was the adopted son of Baji Rao II, the last Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, who had governed from 1795-1818. Upon the death of Baji Rao in 1851, the East India Company refused to acknowledge the terms of his will that granted Nana Sahib an honorific title and annual pension, as Nana Sahib was not Baji Rao’s natural born heir.

This fuelled Nana Sahib’s discontent and his wish to overthrow the British and restore the Maratha Confederacy.

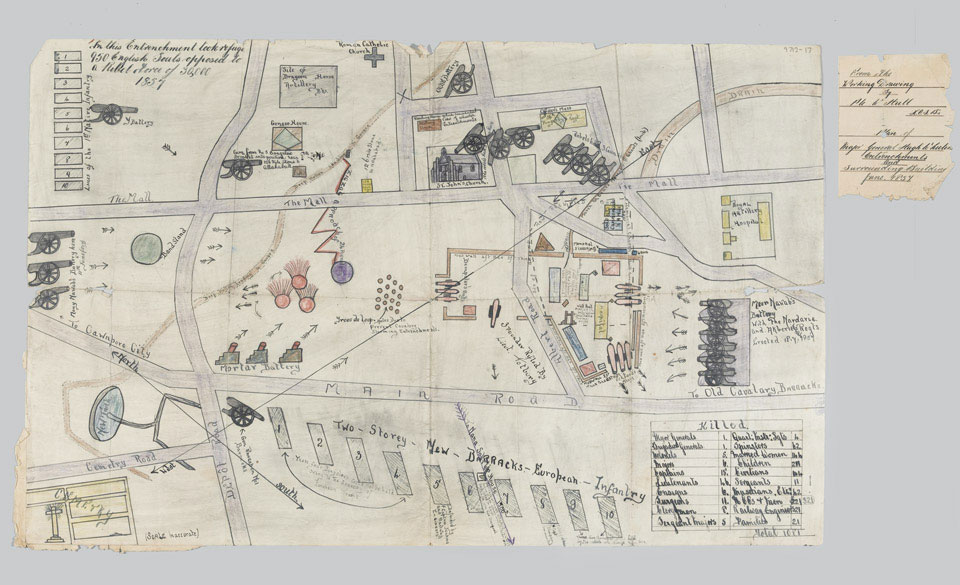

The garrison at Cawnpore was commanded by Major-General Sir Hugh Wheeler (1789-1857). When news of the outbreak of the Uprising reached Wheeler, he, along with approximately 1,000 European residents of Cawnpore, including women and children, retreated to an entrenchment located just outside the city. Sepoys (infantry soldiers) laid siege to the entrenchment with Nana Sahib’s support.

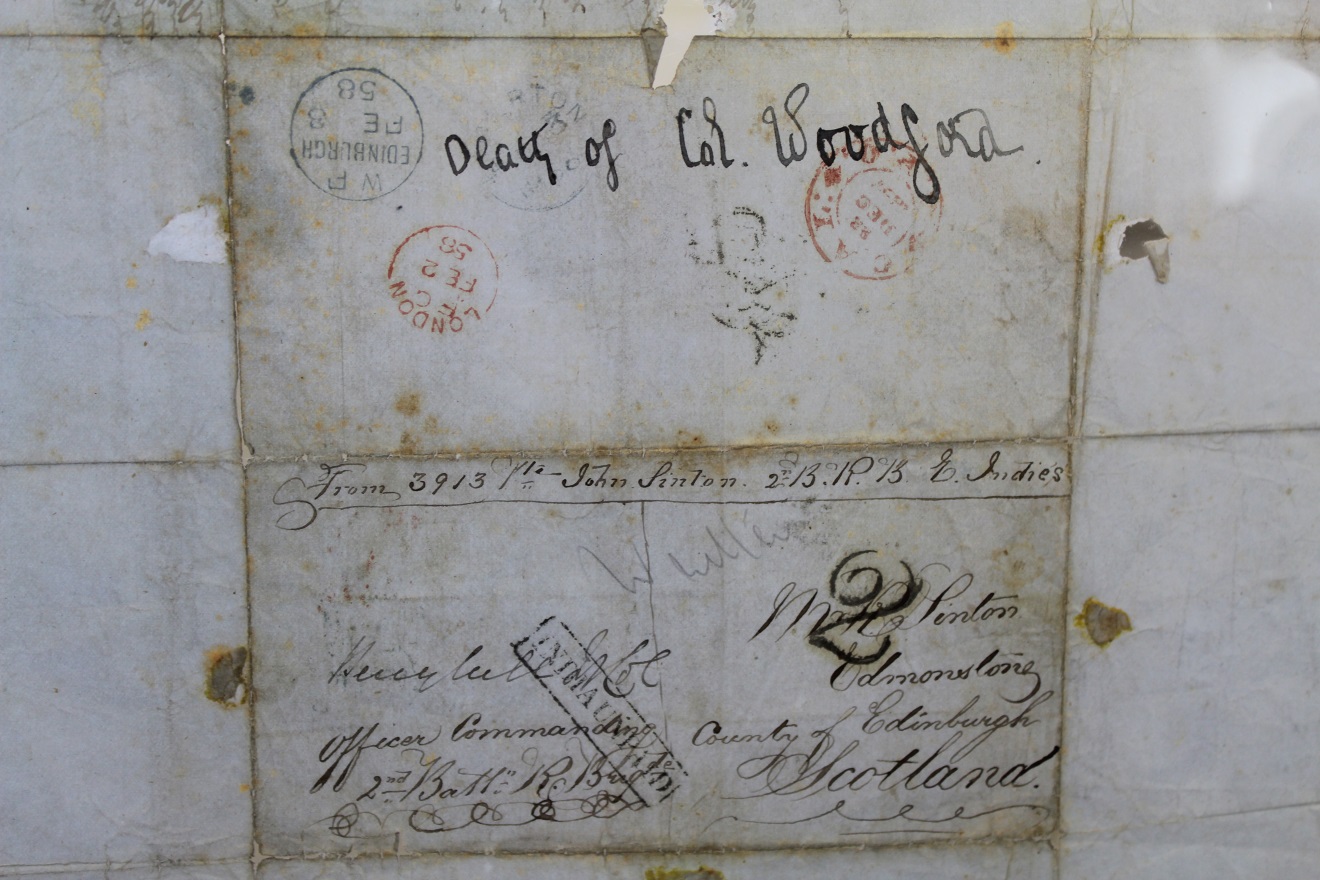

A relief force led by Major-General Sir Henry Havelock (1795-1857) set out from Allahabad to rescue the besieged. After approximately two and a half weeks, Wheeler and his garrison surrendered to Nana Sahib on the promise of being offered safe passage to Allahabad by boats. The embarkation point was to be the Satichaura Ghat on the River Ganges. However, for reasons that remain unclear, as the captives began to board the boats provided by Nana Sahib they were ambushed by rebel sowars (cavalry) and sepoys, leading to the death of Major-General Wheeler and many others. Men who survived the ambush and failed to escape were killed. Whether or not Nana Sahib issued the orders remains unclear.

The approximately 120-125 women and children who survived the ambush and other captives (including senior officials and six drummers of the 6th Native Infantry) were subsequently imprisoned in a compound known as the Bibigarh which was situated near to Nana Sahib’s new headquarters at the Old Cawnpore Hotel. When news reached Nana Sahib that Havelock’s rescue party were near, the captives (estimated numbers vary between 200-206) were put to death. Due to hesitation on the part of some of the sepoys requested to undertake this task, a member of Nana Sahib’s personal body-guard, Sarvur Khan, and four associates were enlisted, and they proceeded to murder the captives. The following morning, sweepers were ordered to throw the bodies of the victims into a nearby well.

This became known as the ‘Cawnpore Massacre’. In response, the British enacted indiscriminate severe and bloody reprisals. News of the murders spread quickly, inspiring an intense desire for revenge amongst British troops stationed in India and a lack of trust for Indian sepoys, causing a disregard for evidence of complicity. Those convicted of rebellion – including the guilty and the innocent – were punished by being blown out of the mouths of cannons, a Mughal punishment the British adopted for these purposes. Rulers believed by the British East India Company to have aided and abetted the rebellion – including Nana Sahib – were pursued for imprisonment or exile. Nana Sahib escaped, and his exact fate remains unknown.

The Cawnpore Cross

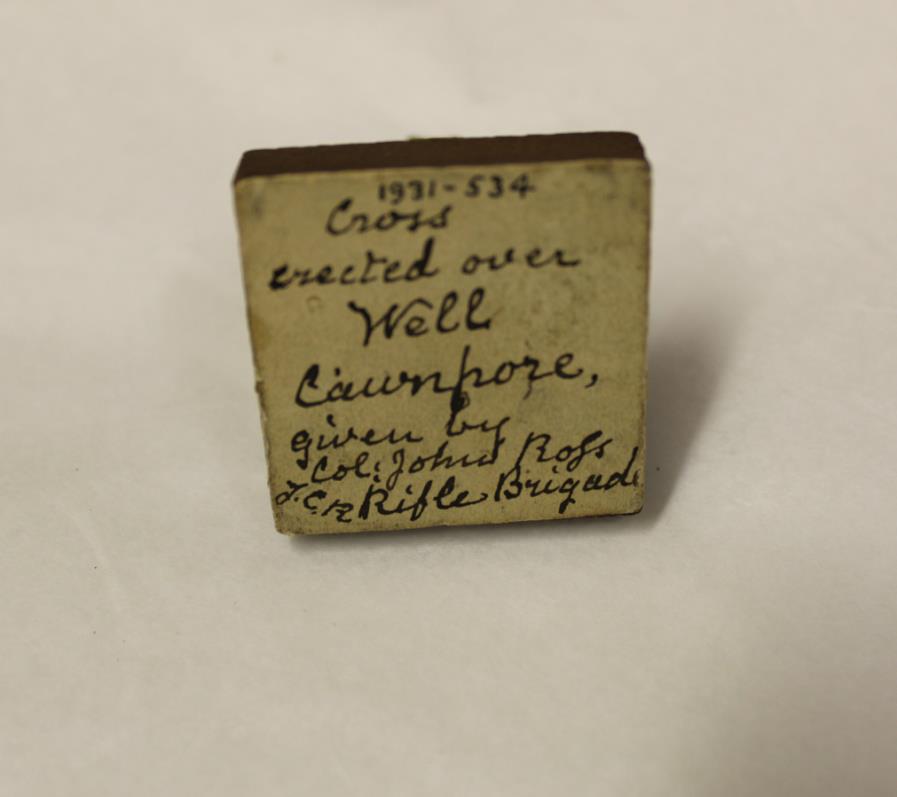

During my initial exploration of the military collections at National Museums Scotland I discovered an object identified as a ‘Wooden model of the cross erected over the well at Cawnpore’. From the description I anticipated a rather large object, and was surprised to find that it was a miniature, measuring only 5.5 cm in height, on a base that is 4 x 4 cm.

Under the base of the small wooden plinth made for the cross there is a handwritten label stating that it had been given by Colonel John Ross of the Rifle Brigade. Ross was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade in 1846, and after seeing active service in the Crimean War (1853-6), he was promoted to Major and went out to India in 1856, seeing service during the Uprising at Lucknow and, importantly, Cawnpore.

An old museum card catalogue found with the object locates the piece in well-described historical and biographical context:

Small Copy of the Cross Erected Over the Well at Cawnpore to commemorate the MASSACRE there of 206 Europeans, mostly women and children, by order of the NANA SAHIB, on the 15th and 16th July 1857, during the INDIAN MUTINY of 1857-58. This little Cross was made by a soldier from the wood of a Tree growing near the scene of the massacre, and given to Colonel John Ross of the Rifle Brigade at the time.

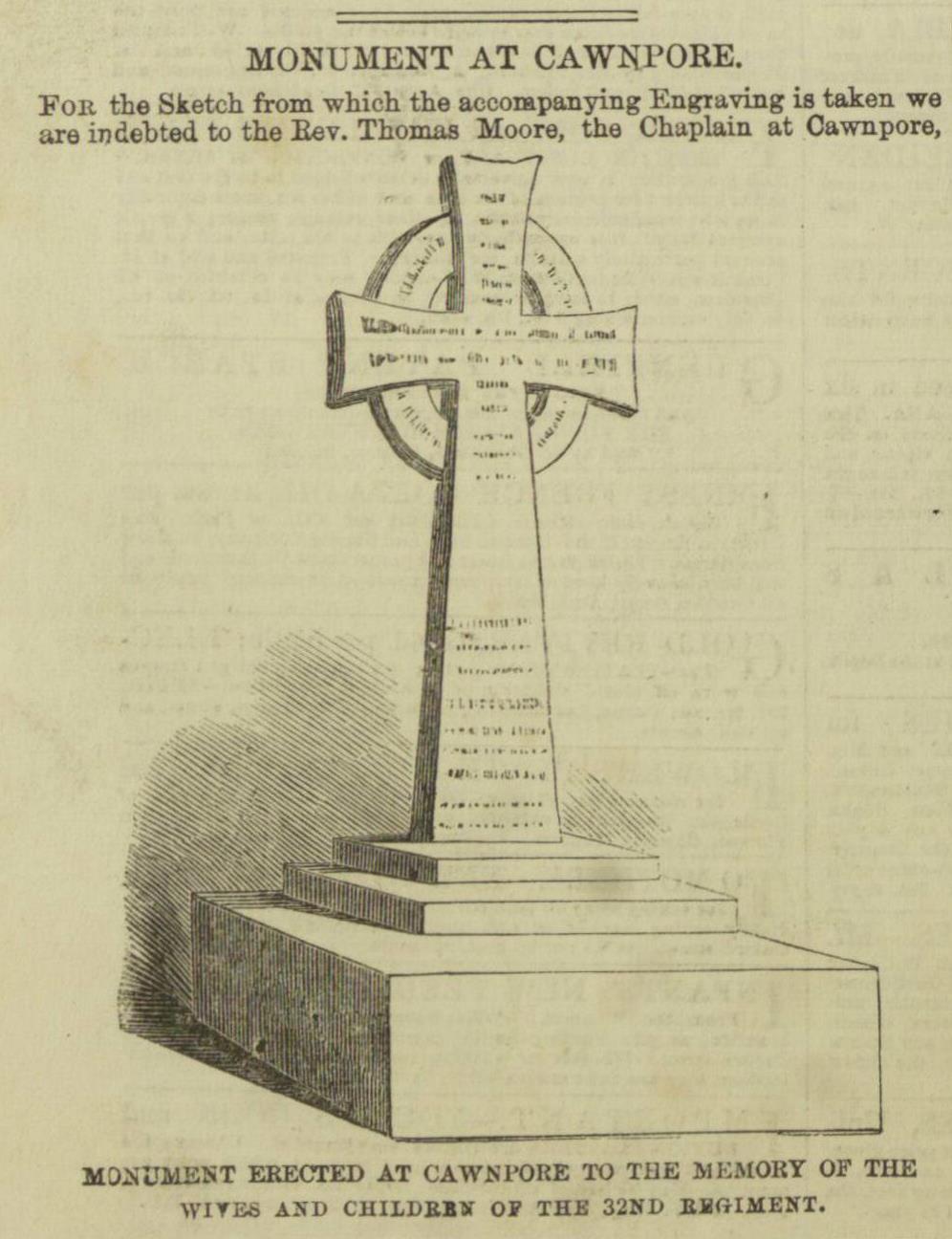

In the aftermath of the conflict, Britons in India and abroad sought to create memorials near to the well at Cawnpore to commemorate those who had lost their lives. Our miniature cross is based on an existing full-sized stone cross seen in the photograph above taken in 1858 by Dr John Murray (1809-1898), a Scottish officer of the Indian Medical Service (Bengal). The monument was dedicated specifically ‘to the memory of the wives and children of the 32nd Regiment’.

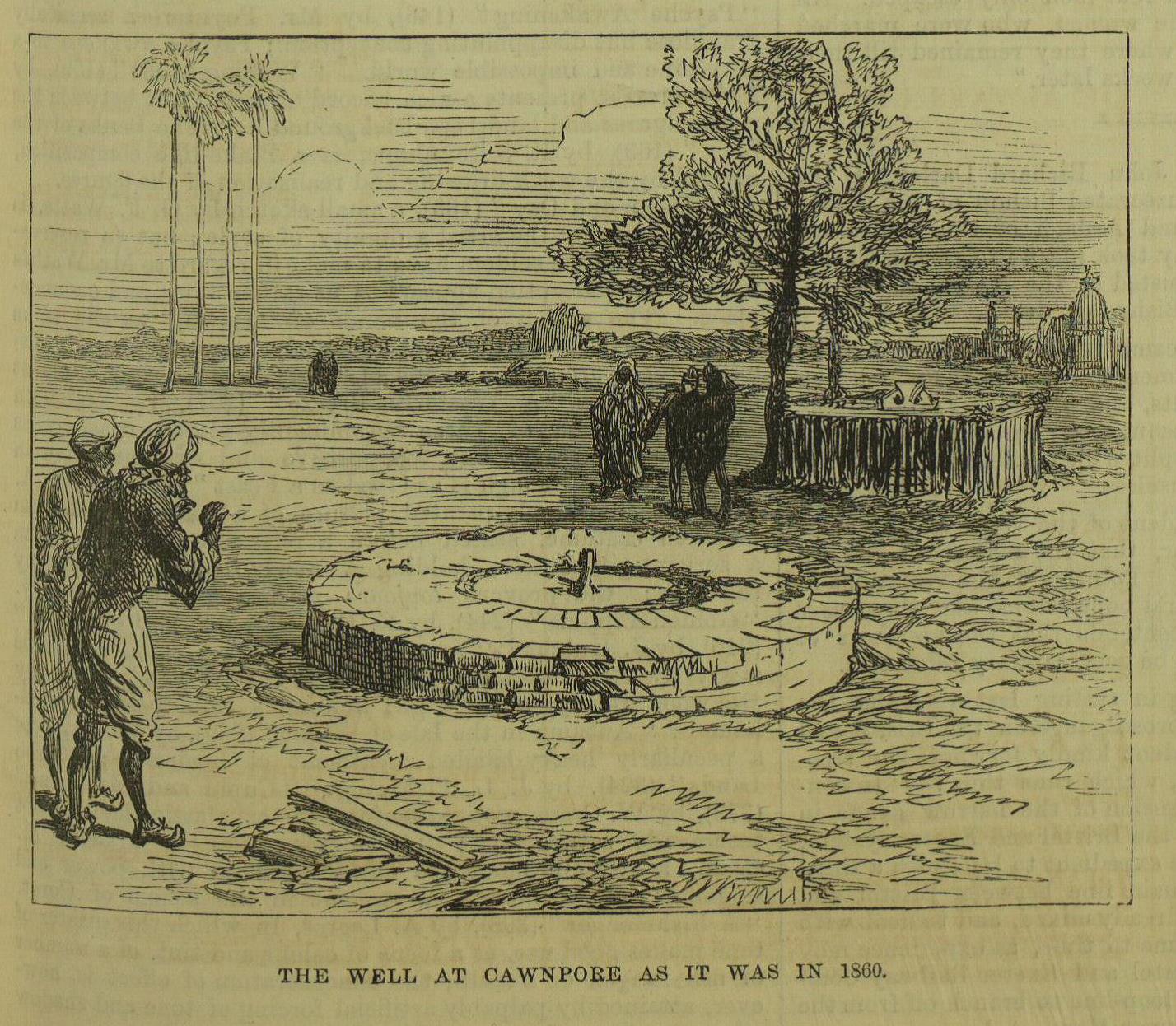

In 1874, the Illustrated London News published a short account of the memorial situated near the well written by the Scottish war artist William Simpson (1823-1899), who had visited Cawnpore in 1860. In this account, Simpson provided a brief description of the cross, which he referred to as ‘… the small Iona cross, of red sandstone, erected in memory of the women and children of the 32nd Regiment’. Simpson’s illustration of the memorial was printed in the Illustrated London News. A reproduction of the cross can be seen in the top right-hand section of the image.

In the aftermath of the Uprising a number of proposals were made for further commemorations at the site of the well. The conclusion was that the well should be enclosed. A design submitted by the Scottish Colonel Sir Henry Yule (1820-1889) of the Bengal Engineers was approved, which included an octagonal Gothic memorial screen to be built around the well. Lord Canning, Governor-General of India (1856-62) and Lady Canning commissioned the sculptor Baron Carlo Marochetti to create a figure – known as the Angel of Pity – in white marble to sit atop the well.

The Indian Uprising and its attendant horrors, one of which was the Cawnpore Massacre, shook British understandings of their place in India to the core, ushering a change in governance. The surrounds of the memorial were landscaped into a public garden financed by a levy on Indian residents of the area around Cawnpore who were, however, unable to enter the site without an authorised permit; a policy that demonstrates how fractured British-Indian relations had become.

Cawnpore and its Memorial Garden became a site of pilgrimage, with many Britons, civilian and military, buying souvenir photographs and postcards of the statue and the memorial screen. Historian Andrew Ward notes that visitors to the site in the late 19th century exceeded those to the Taj Mahal.

What is emerging from my research into military collections is a pattern to collecting. It is clear that the British Army were avid collectors of military trophies, natural history specimens and objects connected to key military commanders – both allies and enemies. The existence of the miniature Cawnpore Cross also demonstrates that they sought to acquire objects that acted as a form of ‘imperial mourning’ and resonated on a deeply personal level.