A very long cardboard box arrived in my office a few weeks ago. Things arriving unannounced in my office are not unusual, but the size of the box was. I knew what was inside, but I had to contain my excitement and wait until we could freeze the box and its contents at -30°C for a few days to kill off any potential stowaway insect pests.

A couple of weeks later in the Vertebrate Biology research collections at National Museums Collection Centre, I opened the box and the large bag inside to reveal the skin and skull of a male wildcat, Felis silvestris. This important specimen had been donated by Dr Pat Morris, who is famous for his conservation work on hedgehogs and hazel dormice. Dr Morris told me that he was given the wildcat by Mr William Kingham, a grocer from Effingham, Surrey, who kept a private collection of British wildlife. Mr Kingham gave most of his dead animals to Dr Morris during his schooldays, so that he could practice taxidermy and preparation of study skins. These skins have been used countless times over the last 50 years and are still used by Dr Morris in mammal identification courses.

This wildcat skin had been prepared for research use and hence was not in the typical snarling pose of most wildcat taxidermy. Instead, it fits snuggly into a drawer so that it can be kept pristine for research.

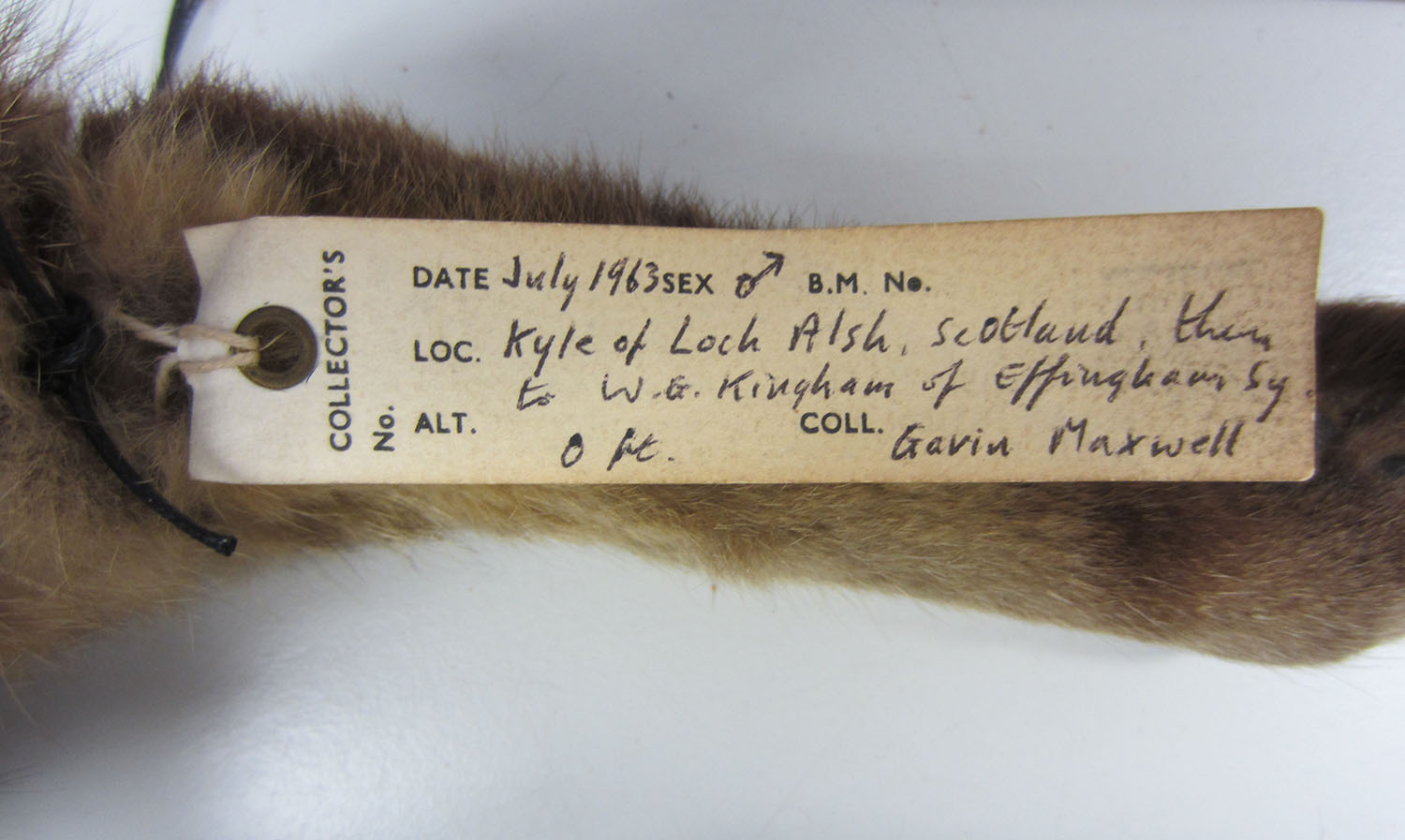

Its label revealed a fascinating history. From the Kyle of Lochalsh, under “FIELD NOTES” Dr Morris wrote: “found swimming in water several hundred yards offshore”. This was very strange. Wildcats do sometimes swim, but I’d never heard of one swimming so far away from land. Even more interesting, the collector was Gavin Maxwell, author of Ring of Bright Water. A quick search on Google Books found in Chapter 13 of Ring of Bright Water a long account of the discovery and rescue of this half-grown wildcat at sea in September 1959.

The wildcat was rescued by Jimmy Watt, who was in the boat with Gavin Maxwell at the time. From being rather meek and mild when rescued, it returned to its normal ferocious state once dried out in a wicker basket. Maxwell contacted mammologist Maurice Burton about a possible home for the wildcat and he suggested Mr Kingham, who drove a 700-mile round trip over three days from Surrey to collect it, but not before it had escaped up the chimney of Maxwell’s cottage!

This particular wildcat is quite famous, having been photographed snarling (inevitably) by Geoffrey Kinns, the photographer at the Natural History Museum and appearing in books and magazines during the 1960s and 1970s. It died in July 1963 and has been in Dr Morris’s collection ever since, until he donated it to National Museums Scotland. We will be taking a small skin sample from the wildcat to examine its DNA as a part of a collaborative study to look at the history of hybridisation between wildcats and domestic cats in Scotland with Dr Helen Senn of the WildGenes Lab at the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland.

You can find out more about Scottish wildcats, including how to identify one and how research, campaigning and breeding programmes are helping conserve this rare animal, on the National Museums Scotland and Scottish Wildcat Action websites.

Header image: Scottish wildcat in the Survival gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.