Lifting the veil of the future has been a concern for humans from the beginnings of ancient Rome to modern-day horoscopes. Many methods have been employed in the attempt to predict an ever-changing fate.

However, in its sophistication, elegance, and organisation, few can rival the divination practices of the late Shang dynasty (c.1200–1050 B.C.) in China. Divination at court was controlled by the king, and its practice was a tool to legitimise his position as an intermediary between this world and the worlds of his ancestors and those unknown. The Shang-dynasty monarchs and their diviners were making predictions about the outcome of battles, the weather, childbirth, the cause of sickness and how to cure it, etc.

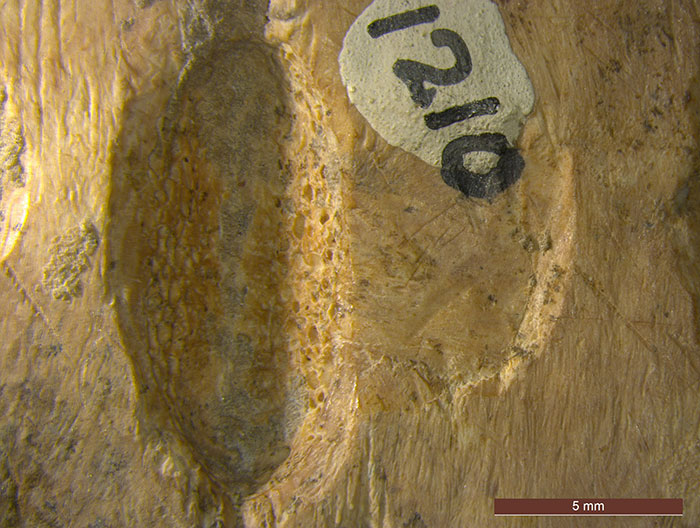

These prophecies were the result of highly complex preparations on cattle scapulae and turtle plastrons to which heat was applied. The thermal shock would fracture the osseous tissue, producing cracks that were interpreted as signs for predicting the future. In order to gain some control over the path of the breakage, a groove was carefully carved deep enough for the bone to crack there first, providing the baseline to which a secondary crack could connect. This created a 卜-shaped fracture. Once the prediction was made, the outcome was in many cases carefully carved into the oracle bone for record keeping.

When I was approached by Prof Joachim Gentz and Dr Elena Kranioti from the University of Edinburgh to participate in a study of Shang-dynasty oracle bones, I had no idea that the collection held at the National Museums was so extensive. Numbering 1,300 pieces, it is the second largest collection of Chinese oracle bones outside China. They were bought by the National Museum of Scotland in 1909 for £100 from Samuel Couling (1859–1922), a British missionary in Shandong who collected them with Frank Herring Chalfant (1862–1914).

The inscriptions carved on the bones are the earliest examples of Chinese script and for that reason have been extensively studied in the past century. A more analytical study of these bones as artefacts, however, had never been undertaken on the Museum’s collection. Our research aimed to examine the backside of the pieces, and to study them with modern, non-invasive and non-destructive techniques to understand how those cracks were made, how the Shang diviners achieved such control over them, and what preparation the bones were submitted to prior to their use.

Most of the research was conducted in the laboratories of the National Museums Collection Centre in Granton, to the north of Edinburgh, with the assistance of Dr Lore Troalen. We used a wide array of techniques such as X-ray fluorescence to look for trace elements, stereomicroscopy to better understand how the bones were carved, scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and photogrammetry, along with investigative techniques of forensic anthropology.

The bones were analysed, in particular, to look for tool marks and residues, something no one had done to such an extent before. We are currently building a comprehensive database, bringing together all the data, photographs, transcriptions and translations of the inscriptions, as well as 3D models. In parallel, we are conducting experiments to recreate the controlled cracks. By approaching the puzzle on two fronts, analytical and experimental, we can test what we discover in the labs to see how it might work in the real world. Inversely, some discoveries made by recreating the process suggest avenues of investigation for traces on the bones to confirm our theories. For example, using X-ray fluorescence we discovered trace amounts of copper in the area where the heat was applied and nowhere else, therefore indicating that the implement used to deliver the heat to the bone must have been made of copper-alloy. We then used metal rods in our experiments, which in turn showed us that it is possible with a simple campfire to reach incandescence and a sufficient temperature to stress the bone into fracturing along a 卜-shaped crack, resembling those observed on Shang-dynasty oracle bones.

This research is a collaborative project between the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, and the National Museum of Scotland. It has been fully funded by the University’s Challenge Investment Fund and we are currently applying for additional funds to further pursue this fascinating study.

You’ll be able to see a selection of the Museum’s oracle bone collection when our new East Asia gallery opens in 2019.