How do we know how far and where fish, and other animals, travel? Nowadays, many have had their movements and migrations tracked with satellite tags, which show where they are over periods of weeks or even months.

For fish, the first example of such tracking was carried out by Professor Monty Priede of the University of Aberdeen off the west coast of Scotland, near the Isle of Arran from 27 June 1982.

At 66cm, the necessary electronics and its waterproof, floating case was fairly bulky, so the researchers chose a large fish. This was a plankton-eating basking shark, and they had a considerable wait for a suitable one to be spotted in a convenient location close to shore: ‘The tag was ready in 1981 but we could not find a basking shark off Scotland in that summer so we waited until summer 1982.’

They successfully attached their pack of electronics to the 7m long shark with a 10m line, so that it would float on the surface when the shark was basking near the surface. This was necessary as the transmitter could not communicate with the satellite when under water.

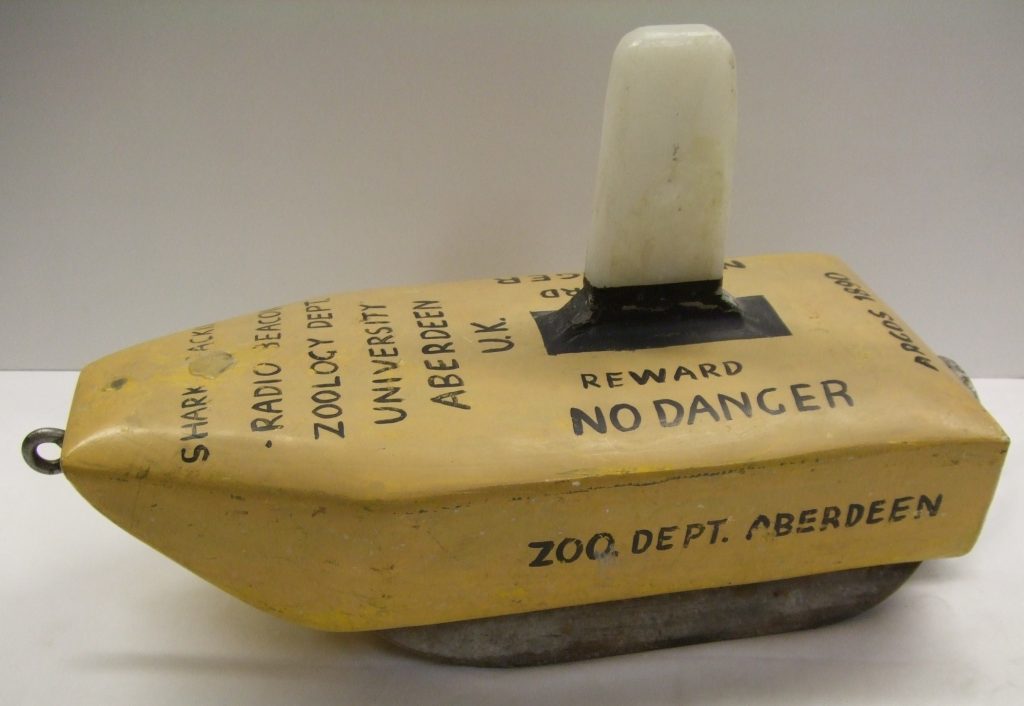

After 17 days the line broke and the device, labelled with foresight ‘REWARD. NO DANGER’ washed up on the shore. The satellites continued to track it to the beach, and then as it continued across Scotland to the researchers’ slight puzzlement. They later learnt it had been put on the back of a lorry to get it back towards Aberdeen.

This, the world’s first satellite tracking tag for a fish, was only used on this one occasion. The research didn’t stop, however, and modern tags are so much smaller that they can be used to track the movements of salmon.

The second tag in our collection also has an interesting story. It was used by a team from Marine Scotland Science in a project which was the first research in Europe to use satellite tags on maiden salmon (salmon that are spawning for the first time), seeking to determine how they might be affected by future offshore renewable energy projects.

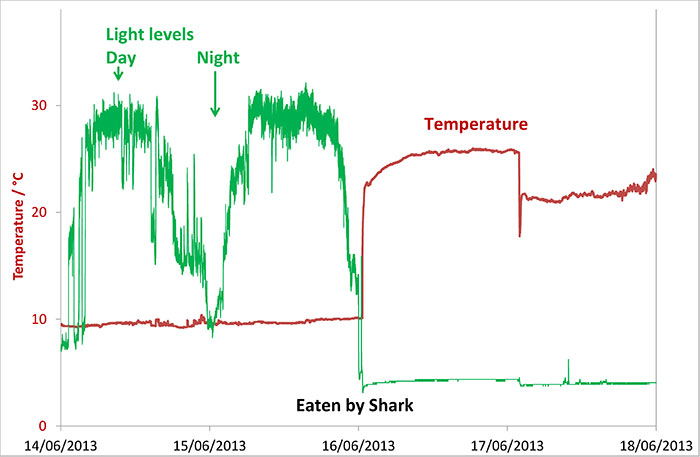

The tags collected data, including the light levels, temperature and depth, but could only record their position once they had released from the fish and were on the surface to receive satellite signals and send back the accumulated data.

The data showed that about midnight on 16 June 2013 this tag suddenly got warmer and darker, and the average depth got deeper. What had happened? The salmon had probably been eaten, tag and all, by a shark. When the tag was eventually recovered it had tooth marks to back this up, but was still working perfectly despite passing through a shark’s digestive system. This would not have been a basking shark as they only have tiny teeth and are filter feeders eating plankton and small fish, not large salmon.

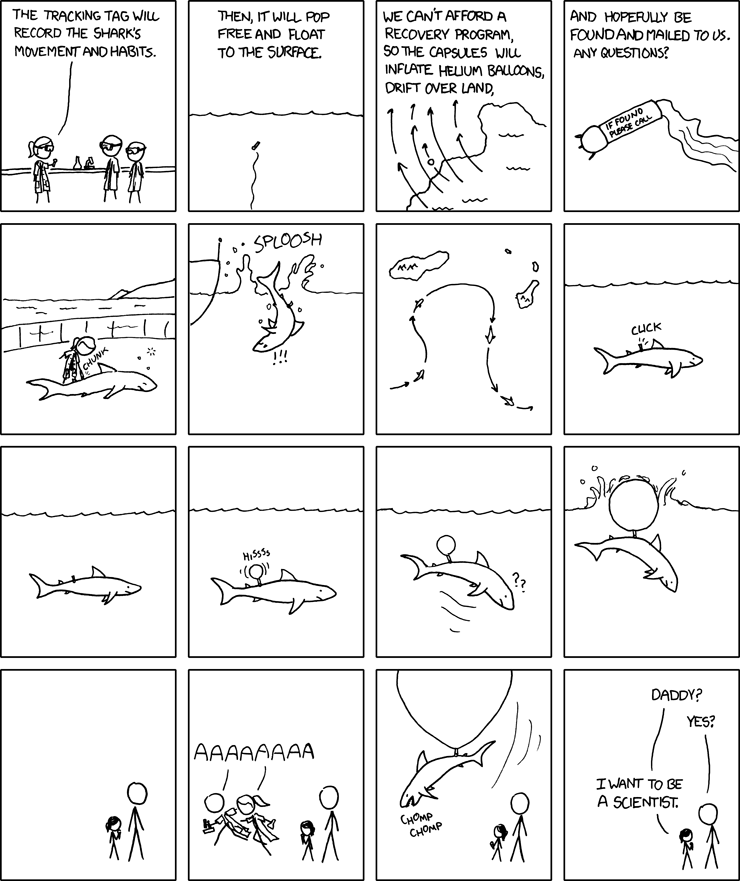

This type of research was featured by one of my favourite cartoonists.

Further reading

- Priede, I.G. (1984) A basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) tracked by satellite together with simultaneous remote sensing

- Marine Scotland Migrating Atlantic salmon findings published

- Godfrey, J.D., Stewart, D.C., Middlemas, S.J. & Armstrong, J.D. (2014) Depth use and migratory behaviour of homing Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Scottish coastal waters