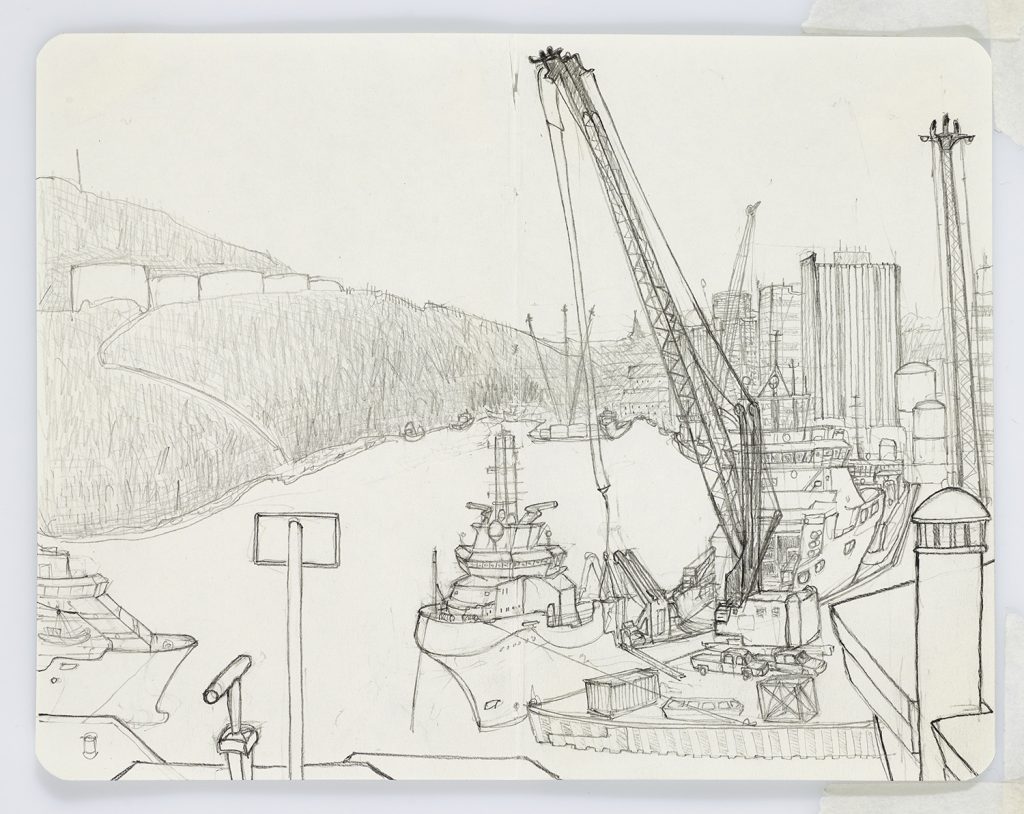

St John’s in Newfoundland is a city of real character, located in the shelter of a busy historic harbour-bay port. Big shipping vessels line its docks servicing the oil and gas industry and Atlantic maritime activities.

Last September I attended Petrocultures2016: The Offshore conference held at Memorial University in St John’s – my first trip across the big pond.

The conference was a fascinating four-day mix of discussion and debate, listening to academics and artists present their papers on particular subjects around fossil fuel and its damaging effects in the age we live in – The Anthropocene Period. Apart from a Norwegian guest speaker, I was a bit of an oddball describing my own offshore experiences. Listening to academics talking about their research brought some parallels to the North Sea, such as the Newfoundland oil worker’s migratory work movements throughout Canada: the lure of lucrative wages on pipelines and tar sands throughout the distant Canadian provinces.

Our first day was a group visit to Bull Arm Construction Yard, Trinity Bay, where the Hebron Gravity Based Structure platform was being fabricated. A full bus party travelled out to the site, two and a half hours north-west of St John’s along the Trans Canadian highway. Just like the US, this country loves its big trucks. We were met by the company’s PR lady in the Bull Arm exhibition and information centre. She gave us a scripted and well-rehearsed tour, firstly in the exhibition area and then a bumpy ride in a vintage North American yellow school bus down to designated shoreline viewpoints. On the way, we passed the workers’ accommodation campsite, long lines of three-storey weatherboard buildings.

At the two viewpoints, we could just get a glimpse of the massive module construction site in the next shore inlet about a mile away. Out in the bay, the gigantic concrete sub-sea structure was being built. These constructions were brutal and massive in scale; it was very frustrating that we could not get closer. Back home on my industrial site visits, I was used to open access.

Despite this constraint, it was a new experience for me, the industry set in another rural and remote environment. Hebron was to be the fourth offshore development located 350km south-east of St John’s, in the Jeanne d’Arc Basin off the Grand Banks; it was joining Hibernia, Terra Nova and White Rose. Interesting to me, a Scot, was that this field was named Hebron-Ben Nevis Field.

This construction had similarities to North Sea concrete sub-sea structures such as the Brents and, in particular, CNR’s Ninian Central, but the waters were shallower (93 metres compared to the northern North Sea’s 140 metres depth). I was astounded to learn that its reserves were 400 to 700 million barrels of thick crude. Unlike our northern seas, Hebron will have passing icebergs to deal with; its location is known as Iceberg Alley. Like its sister platforms, it will have protective devices on its concrete leg to combat iceberg collisions.

Offshore worker Tonya Lane, St Chads

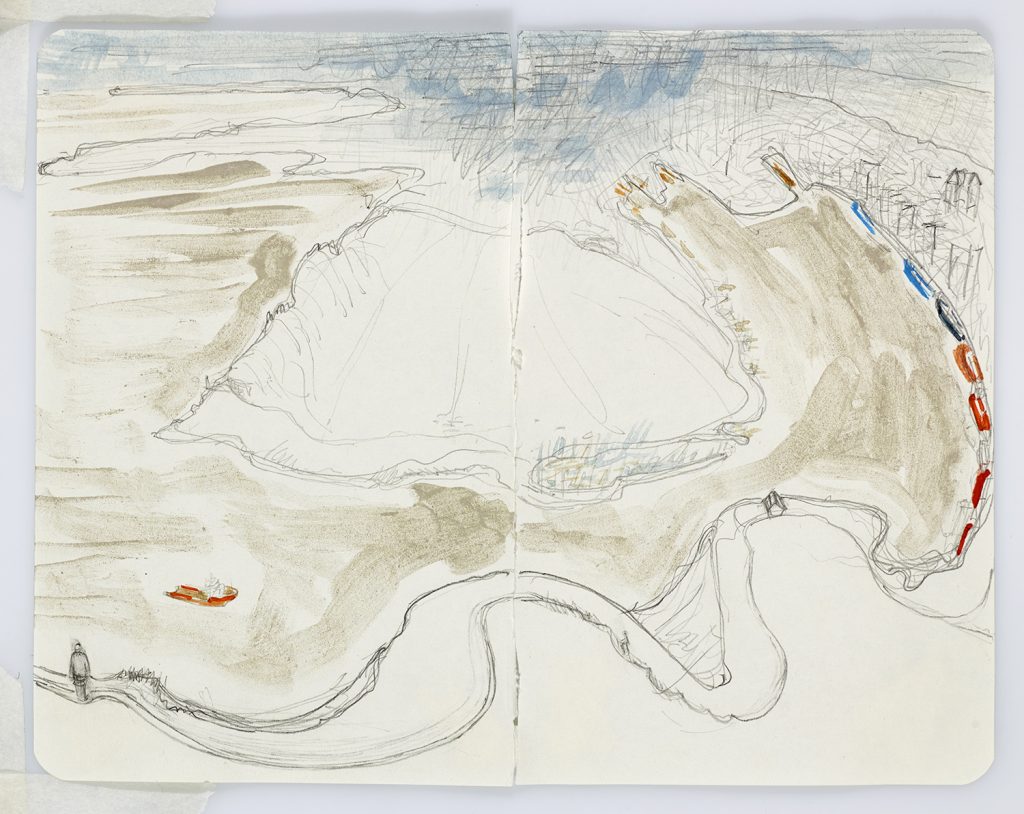

After the conference, I had an opportunity to meet up with a Newfoundland offshore worker. I travelled out by bus to Eastport Peninsula, five hours west of St John’s, to meet with up Tonya Lane, who had worked offshore in the Jeanne d’Arc Basin and in West Canadia’s tar sand camps. Tonya was still travelling around the world but I was lucky to catch her in St Chads at her folks’ place. As soon as I got off the bus she took me on one of Terra Nova National Park’s trail tracks. At the top of a giant boulder, we looked out onto an Atlantic Canadian panoramic vista. It was idyllic in the heat of the day, vast swathes of small-sized native trees from broad leaves to conifers interspersed with inlets and bays.

I was made very welcome by her family who, on both sides from way back, were Newfoundland livyers* who settled in Eastport Peninsula. St Chads was a beautiful location by the sea, weatherboard houses originally transported here on the ice. Tonya often liked to sleep in her dad’s boat house with its own wooden jetty, where he kept his lobster creels and fishing tackle. From there she regularly kayaked out in the bay.

Her dad was about to retire from fishing, her brother was not interested in carrying on the family boat. He worked as a welder at Bull Arm construction site and lived in St John’s. For generations, the family had fished mostly cod off the Labrador coast. Her mum, who had helped on the family boat all her life, was known as one-shot Mary as she was a crack rifle shooter. She was also a staunch Coronation Street fan* and her dream was to have a drink in the Rovers Return TV set. Inland the family had a cabin for weekends and during the shooting season they hunted moose and caribou. Tonya had just got her gun licence and would shortly be taken hunting for her first moose.

It was berry season and an abundance of blueberries, cloudberries, partridge berries and snow berries were all growing wild. We picked buckets of blueberries for dessert and breakfast. I was even brave enough to sample their local delicacy: pan-fried cod tongue, nape and cheeks. Whilst Tonya took me on more trail walks she told me to be aware of black bears as one had been sighted nearby recently and we had to make loud noises whilst walking in the bush. Coyotes also roamed around at night. The landscape and rural lifestyle reminded me of when I lived in Scandinavia with its abundance of trees, rocky inlets and bays.

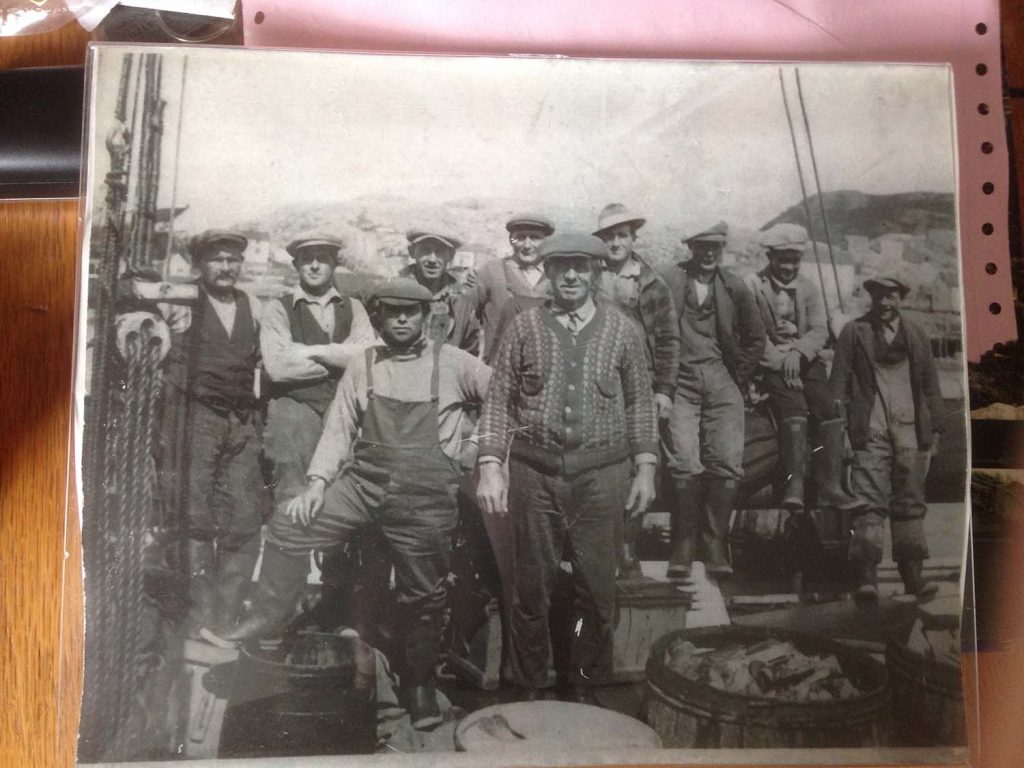

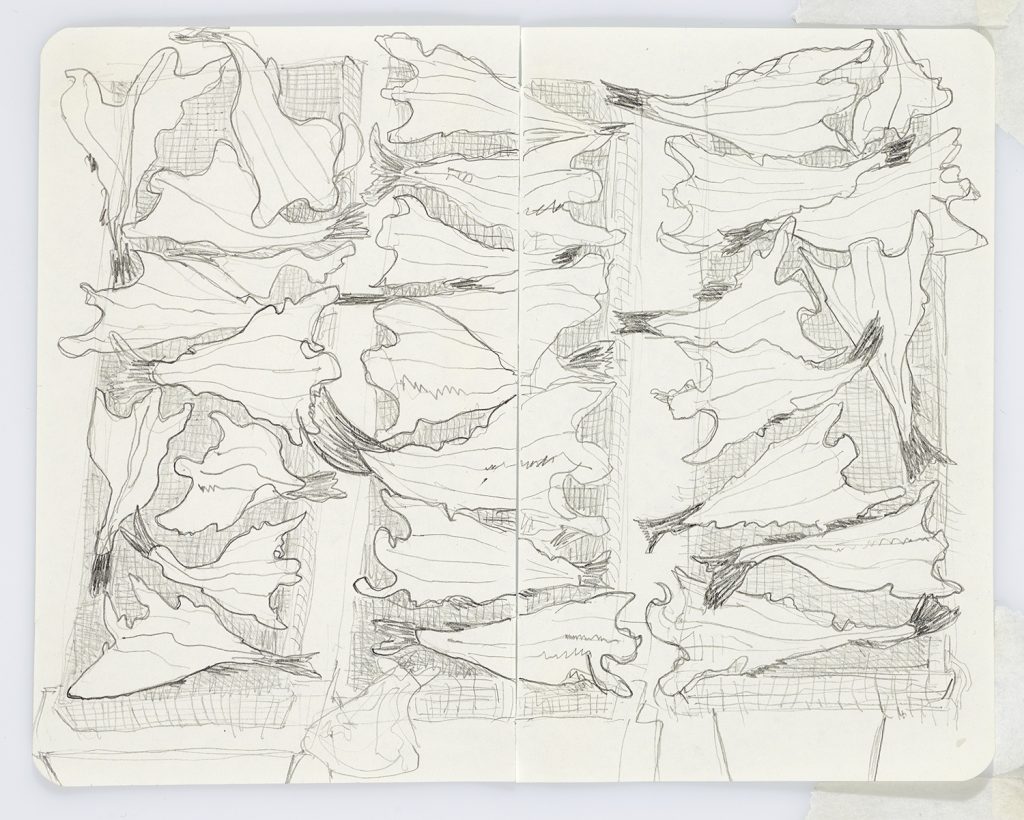

Giant gutted cod lay on drying racks by their big barn, wonderful imagery for me to draw. Tonya’s dad told me that these were small compared to what they used to catch. He blamed fishing fleets from outside Canada such as the Spanish for the depletion of cod stocks throughout the years. There were now tighter restrictions and quotas in place with which to control and increase the fish stock.

Tonya spoke of her time offshore and in the tar sand camps with mixed blessings, very tough for her at times. She was curious to see for herself why so many Newfounders, or Newfies as they are known, worked far away from their home in extreme locations, a sacrifice solely for the money. She had worked as a stewardess on sites such as the Floating Production Storage and Offloading vessels in Terra Nova field and at Alberta and in Northern British Columbia tar sand camps. It was interesting hearing her speak about the differences in work environments. Offshore money was more secure and as a woman, you were treated well. She always looked forward to the weekly muster drills, a treat going outside to glimpse the sea and look out at the supply and standby vessels bobbing up and down.

The camps were a different story, really tough. The ratio between men and women was similar to that offshore, very few females, but the attitudes from male camp workers were not so good. For her, the feeling of isolation was greater in the camps than working offshore. As she drove me back to the bus stop in the big family Ford pickup truck, she told me her years of working away in oil-related industries were behind her and she was looking forward to joining a Norwegian tall ship for a year before settling back in St Chads.

The Age of Oil exhibition was on display at the National Museum of Scotland from 21 July to 5 November 2017.

An Age of Oil publication featuring Sue Jane Taylor’s works and diary extracts is available to buy here.