The land of Nubia, the region along the Nile south of Egypt (modern Sudan), may be less well-known than its northern neighbour, ancient Egypt, however, it also has a long and fascinating history.

This was the region which connected Egypt and the wider Mediterranean with central Africa, and served as trading conduit for African luxury goods, like ivory, ebony, incense and exotic animals. Nubia was also very rich in natural resources such as gold, copper or semi-precious stones.

In its early history, in the third millennium BC, Nubia was divided into a series of small kingdoms, who controlled the trade and the mines. Egypt, which became a unified kingdom around 3000 BC, had from the beginning great interest in the resources of this region, which they simply called ‘The Southern Land’ or ‘The Land of Bow’, referring to the weapon most closely associated with its inhabitants. This Egyptian interest was manifest in the form of peaceful trading expeditions, but also sometimes in military campaigns and temporary conquests of the various kingdoms. The depiction of defeated Nubians became a common motive in Egyptian art, as illustrated by a statuette in the form of a Nubian prisoner from the collection of the National Museums Scotland.

The traditional southern border of Egypt was the first cataract (shallow length or white water rapid) of the river Nile, where the modern Egyptian city of Aswan is situated today. Around 1500 BC, the Egyptian border was extended more than 1000 miles more to the south, as far as the fifth cataract. The Egyptians ruled this region until around 1000 BC, founding cities and building huge temples in Egyptian style, like the one of Ramesses II in Abu Simbel, which became world-famous after its relocation in the 1960s, because of the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

However, there was a period of time when the Nubians were the ones who conquered Egypt – a period from which the National Museums Scotland has several objects of great interest. In the 8th century BC, a new and powerful Nubian kingdom emerged, whose kings led various military campaigns against Egypt, until finally a king called Shabaqo conquered the land. He and his successors ruled Egypt for 100 years.

These Nubian kings showed great enthusiasm for Egyptian traditions and culture, adopted the royal titulary and iconography, supported the temples and even buried themselves in pyramids built in Nubia. While being keen on upholding Egyptian traditions, they also signified their distinctiveness. The particular features of the royal statuary of this time can be excellently observed on a small bronze royal statuette in the collection of the Museum. It is currently on display at the National Museum of Scotland in the exhibition The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial. Part of the exhibition is dedicated to presenting the changing burial practices in Egypt during the Nubian period.

This small statue was excavated in 1970 by British Egyptologist Walter Emery in North Saqqara (near the modern city of Cairo) and donated to the museum in 1971. In many details it follows the traditional Egyptian royal iconography: the statue represents a pharaoh in a striding pose, wearing a shendyt kilt, a traditional garment of Egyptian rulers. In his right arm, which is slightly bent, he holds a ritual water jar. The Nubian origin of the king is emphasized by his round face, his short and broad nose and thick lips. The figure also wears a new form of headdress that was used only by the Nubian rulers. It consists of a closely fitted skullcap decorated with dotted circlets and of a diadem with a double uraeus (stylized form of an Egyptian cobra, a symbol of royalty) and streamers. This headdress may have represented a metal helmet or its material may have been textile or leather, the circlets being metal decorations.

The statue displays a further distinctive iconographic feature of the Nubian period, namely the neck cord with three rams’ heads. The ram symbolized the god Amun. He was revered originally in the city of Thebes (modern Luxor). He became one of the most important Egyptian deities in 1500 BC, when his cult was also introduced to Nubia, where he became extremely popular. In Egypt he was worshipped in human form, in Nubia, in the form of a ram. The devotion of the Nubian king to his cult was articulated through the frequent depiction of a neck cord with one or more ram’s heads.

Because of the importance of the cult of Amun for the Nubian kings, it is not surprising that they showed a particular interest for the city of Thebes, the centre of the Amun cult, and built up intensive connections with the Theban priesthood. There was, however another important religious Egyptian centre which played a central role in the Nubian royal ideology: the city of Abydos, the cult centre of Osiris, the god of the underworld. There are many objects in the collection of the Museum coming from this site, and one of them is of particular importance to understanding the Nubian period in Egypt.

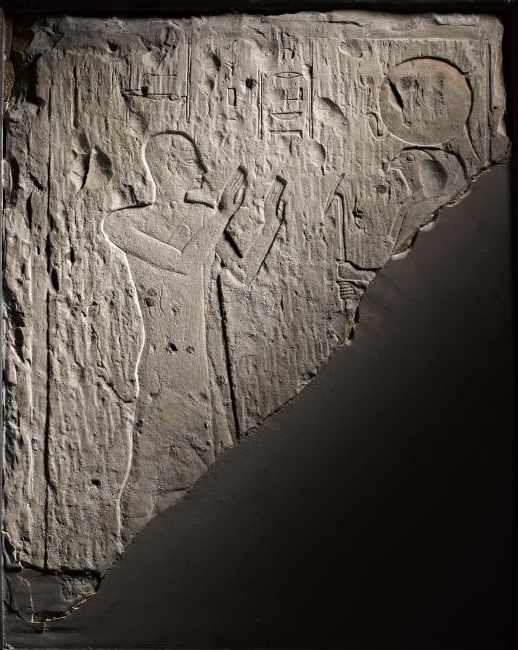

While the Nubian kings buried themselves in pyramids constructed in Nubia, some of their female family members were buried in Abydos, close to the sanctuary of the god Osiris, ruler of the underworld. The tombs of the Nubian princesses were known to Egyptologists already for a long time. However, until recently there had been no tomb of a Nubian prince found in Abydos or elsewhere in Egypt. This changed after the careful examination of a limestone relief of very high quality belonging to the collection of the National Museums Scotland.

The fragment was found in a tomb in Abydos and was gifted to the museum in 1901 by the Egypt Exploration Society. It represents a male figure, identified by the inscriptions as the ‘king’s son’, worshipping the sun-god Ra depicted as falcon-headed and mummiform. At first sight, there is no indication of the ethnic origin of this prince: he has an Egyptian name, Ptahmaakheru, and his facial features do not show any sign of his Nubian roots. There is also no information in the inscription about his father. However, the British scholar Anthony Leahy successfully demonstrated that this relief shows some distinctive features of the time during which the Nubian kings ruled Egypt. The most striking is his cloak, which is a so-called ‘Kushite-cloak’, a garment most probably of Nubian origin. The traces of a rosette band along the edge of the fabric across the chest recall the decoration of the cloak worn by the last Nubian king Tanutamuni in his tomb at el-Kurru, Nubia.

The prince’s name Ptahmaakheru is Egyptian, however it would have been fairly unusual in his time. There is no individual known bearing this name after 2200 BC, while the tomb itself was built around 680 BC. Family members of the Nubian kings occasionally chose such historic names, which were used thousands of years earlier, in order to represent their knowledge and devotion to the ancient Egyptian traditions. This may have been also the case with Ptahmaakheru. Thus, this relief fragment in the National Museums Scotland is most probably from a tomb of a Nubian prince built in Abydos who poses almost entirely as an Egyptian individual.

The Nubian rule in Egypt lasted around 100 years. The dynasty was swept away by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal invading Egypt. The last Nubian king, Tanutamuni had to flee to Nubia, and neither him, nor his successor led another military campaign against Egypt. The history of the Nubian Kingdom, however, did not end. In fact, their empire centred first in the city of Napata at the fourth cataract, and later in Meroe further south, flourished in the following centuries, displaying a very interesting mixture of Egyptian and local traditions – a culture which scholars of the ancient world started to understand in depth only in recent years.

Further reading: Anthony Leahy (2014), ‘Kushites at Abydos: The Royal Family and Beyond’ in Pischikova, Elena et al (eds.) Thebes in the First Millennium BC (Newcastle upon Tyne), pp. 61-95.

The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial is at the National Museum of Scotland until 3 September 2017.

Sponsored by Shepherd and Wedderburn