National Museums Scotland receives hundreds of animal specimens each year. Many are donated by members of the public as road casualties, or mice and voles being killed by domestic cats, or birds flying into windows.

This wide variety of specimens ensures that we have a snapshot of what is happening to local biodiversity by providing specimens and samples for analysis. In this way we can look at problems of hybridisation (e.g. wildcats and domestic cats, or brown hares and mountain hares), diet (e.g. polecats), pollutants (e.g. whales and dolphins), and climate change.

Many also come from zoos and wildlife parks, where they have died of natural causes. Zoo animals offer valuable opportunities to discover more about species which would be near impossible to obtain from the wild, because they are very rare, fully protected and it would be ethically wrong to do so. As a result of the excellent cooperation we have with many zoos in the UK, we are able to offer unique opportunities to researchers in universities to study anatomy.

This demand has grown hugely in recent years, and we have contributed to recently published research on the scaling of muscles in cats, the relationship between muscle mass and brain size in primates and the facial muscles used in facial expressions of Sulawesi crested macaques. And there is much more to come, including the hopping legs of wallabies and kangaroos, the scaling of voice boxes of primates and carnivores, and comparing the skulls of wild and captive tigers and lions.

All of the specimens which enter our collection go through a preparatory process to enable us to preserve key elements for current and future researchers.

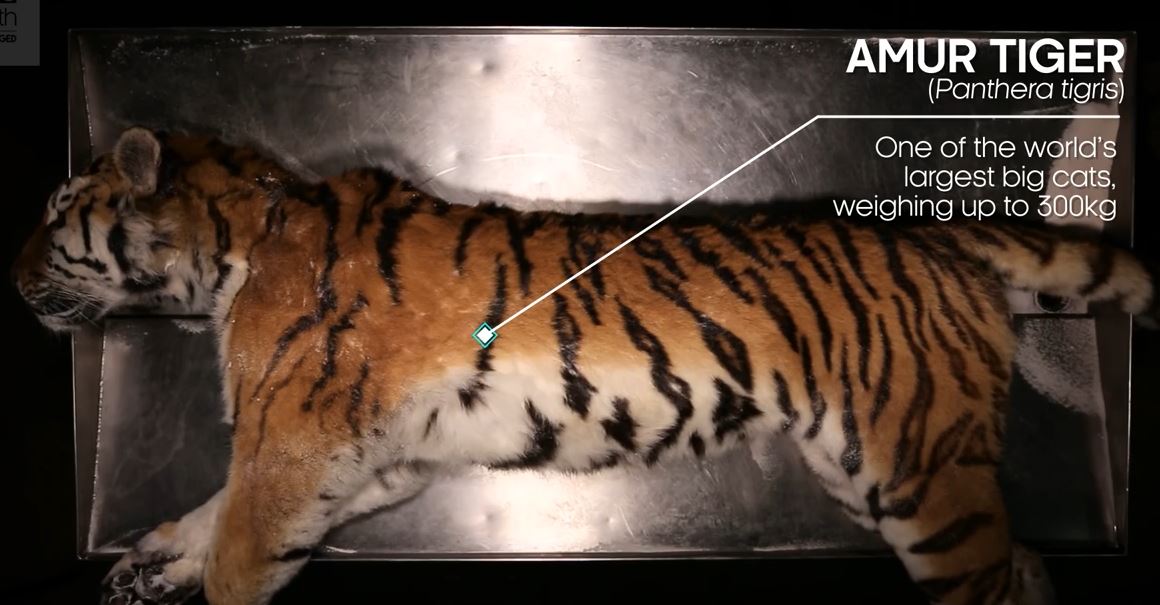

Understandably this careful dissection work goes on behind the scenes, but recently we were approached by the BBC to make two films of the dissection of a tiger for the BBC’s Earth Unplugged YouTube channel. The tiger was a 14-year-old female which came from the Wildlife Heritage Foundation’s Big Cat Sanctuary in Kent. Sadly, she had to be euthanased owing to her failing kidneys, a common problem for wild and domestic cats.

One film is a time-lapse of the process, the other is a longer version with commentary from TV naturalist Ben Garrod in conversation with me and our curatorial preparator Georg Hantke explaining in more detail what we are looking at. Making the time-lapse video involved mounting a camera above the dissection table and taking a series of photographs of the tiger as it was skinned, but without Georg in shot, so that it almost looks as if the tiger is unzipping its fur coat itself.

The films allow us to explore the basic anatomy of the tiger and show how it is adapted to be a lean, mean killing machine. The tiger’s skin, skeleton and a small muscle sample have been preserved for our permanent collections and her internal organs have been frozen, so they will be available for future research.

With over 50,000 views since its publication in mid-February, there is clearly an appetite for these educational films, which helps open up the importance of what we do to the widest audiences.

You can see BBC Earth films of the dissection on YouTube here:

Please note that the videos contains graphic imagery of a tiger dissection which some viewers may find distressing.