National Museums Scotland has a collection of just over 300 carved jades from China, which have recently been collated and re-stored. The carvings range in date from the Shang Dynasty (c.1600-1050 BC) to the late 19th century.

Whenever I mentioned that I was working with the jade collection, it raised some interesting questions: Whilst it’s common knowledge that jade is an essential part of the tradition of Chinese decorative art, people often ask me what it is, and just what makes it precious? As someone who likes to make things, I am also interested in how artists worked with this material, and whether they still use the same techniques today. The recent visit of Ming Wilson from the Asia department at the Victoria & Albert Museum revealed some unexpected collections highlights which I will tell you a bit about in a bid to help answer some of these queries.

The material commonly known as ‘jade’ is actually two types of silicate known as nephrite and jadeite, both of which are mined from large boulders. The purest and most highly prized nephrite jade is white and known as ‘mutton fat’ due to its almost ‘greasy-looking’ texture. It comes from the riverbeds of Xinjiang, northwest China. However, the many colours of jade are well represented in the collection and includes greens (a particularly dark green is called ‘spinach’ jade from Lake Baikal), browns, greys and black. Some carved jade is mottled, due to impurities (iron compounds).

Historically jade was prized for use in carving because it is extremely hard. This seeming indestructibility easily lends itself to metaphorical links with purity and immortality. Jade artefacts were often buried with the deceased – it was believed that a jade ‘suit’ would prevent the body from decay. Smaller objects were placed in the hands of the dead so that these auspicious qualities could be carried into the afterlife. National Museums Scotland has a Han dynasty jade pig which is an example of this – the carving is deliberately simple in order to make the jade itself the main focus.

A great many jades are fanggu, which means jades in imitation of antiques. This incense burner is deliberately shaped to resemble the famous bronzes known as ding.

However, our collection also includes a few excavated items of genuine antiquity. As well as the Han pig, there is A.1938.383. This little circle with a hole is a Han dynasty bi disc – one of the six ‘Ritual Shapes’ representing earth, air and the four directions. This one is likely to be authentic – you can see that the corner has an ‘aged’ appearance, presumably from spending centuries in the ground.

Jade is technically difficult to carve – it’s so hard it can’t be cut with metal tools. Instead it was drilled, sawed or ground/worn away with a foot lathe using an abrasive paste of carborundem sand (synthetic silicon carbide) with water serving as a lubricant. Carving takes months or even years to complete. Because of this, craftsmen have become highly specialised, devoting themselves to specific types of object carving. Carvers can be expert in creating not just figures or landscapes but more prosaic seeming items such as hinges, or knobs for lids.

Jade carving really flourished under the Qianlong Emperor, who reigned from 1735-96 and who particularly prized jade. He is said to have loved carvings for the skill of the workmanship and the intrinsic beauty of the material itself. He referred to this as huayi jade – jade that was able to achieve in 3D the realistic qualities that painters captured on paper – rather than how much the carving resembled those of antiquity. During his 61 year reign, he facilitated the availability of jade by creating the new province of Xinjiang, which was mentioned earlier as a rich source of nephrite.

Because of the Qianlong Emperor’s love for the high quality mutton fat jade, ‘leftover’ pieces were often carved into items in their own right such as hat finials such as A.1887.159 or the knobs lids (used as a handle to lift the lid off).

Rather like modern upcycling, the knob for the incense burner K.2001.551 is an example of this retaining and reusing of jade. It is carved as a one-horned Qi dragon and is older than the main body of the burner. Although it’s small and functional it would have been seen as the ‘best’ part of the object; although the main body is finely carved it’s not the same high quality mutton fat jade as the knob.

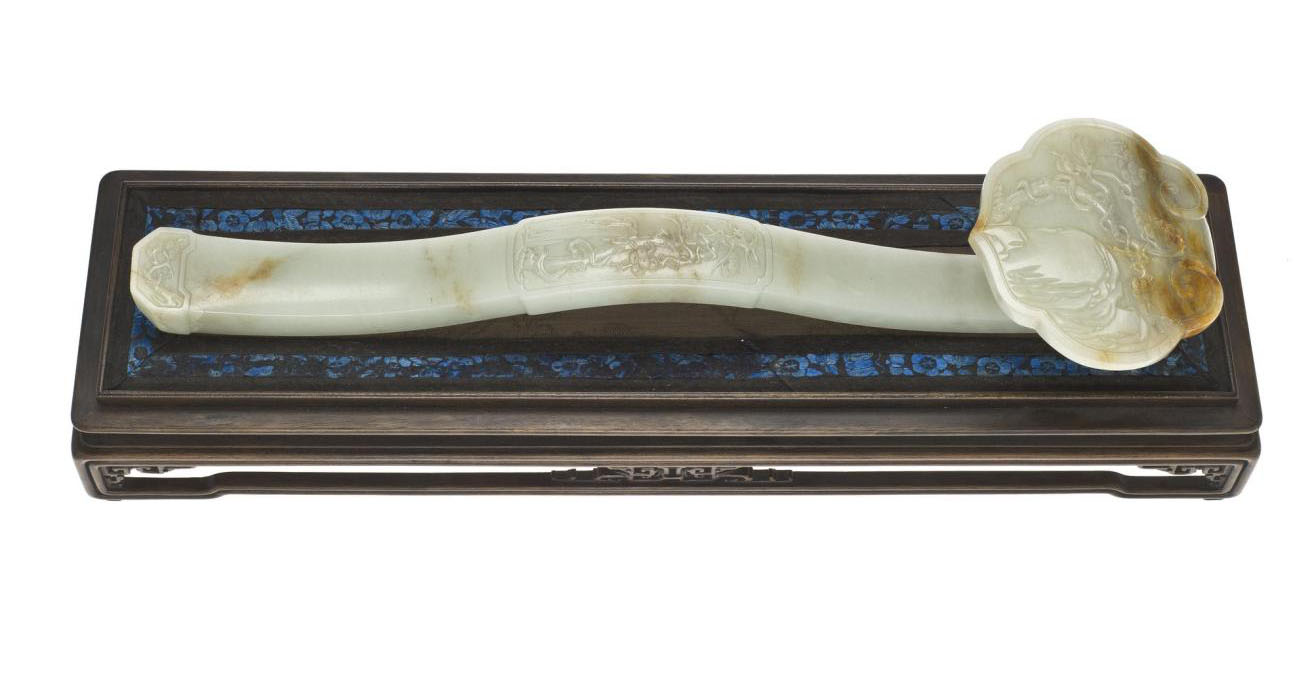

Although porcelain and silk were famously imported to Britain from the 16th century onwards, jade was introduced in the form of ruyi that were gifted in 1793 by Emperor Qianlong to King George III and senior members of the first British Embassy to China.

These unusual objects are described as ‘sceptres’ and were purely ceremonial. The ruyi A.1875.29.12 is an especially striking example in our collections as it reflects a spike in the British interest in jade items in the wake of the looting of the Yuanming Yuan (Summer Palace) in 1860 during the Second Opium War.

This jade item was purchased from the estate of Charles Seton Guthrie in 1875, fifteen years after the looting. Jades of this period became entangled with British Imperialism as much of the jade in the UK in the 1860s/70s was claimed to be looted, in order to hike up the price. The fact that Guthrie was a military man would have added credibility to such claims. However, he served in the Bengal Lancers and was never posted to China. The sceptre is carved in beautifully decorated wood with silver wire decoration and three attached jade plaques.

Carved jades, as with so many East Asian decorative art objects, are often placed on wooden stands, which were intrinsic to their display from the mid-Ming dynasty (1368-1644) onwards. The role of the stands may be compared to the placing of a painted canvas in an expensive frame. These display pedestals are worthy of appreciation in their own right; entire workshops were devoted to their carving.

The stand for the incense burner K.2001.551 is a lovely example, carved to fit the jade precisely. Sadly, this concept didn’t immediately translate to the western market, and stands were often separated from their objects and lost. Many of ours were stored separately and we’ve just completed a project working to reunite the stands with their objects.

I was happy to learn that today the jade carving tradition is flourishing. Carvers still specialise in specific designs such as figures or beasts or hinges or lids in workshops as they have done for centuries.

However, in the 1960s, in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, jade factories broke with inherited tradition by employing carvers based on their talent rather than family links. Renowned contemporary carvers such as Wu Desheng, Zhai Yiweii and Liu Zhongrong started working in these factories while they were still in their teens.

The carvings themselves have undergone changes too. Today, they’re a blend of traditional and modern, pulling away from historically accepted designs to reflect both the changing society and the individual style of each artist.

Technological innovations have also made a huge difference to carvers; rotary tools with diamond bits and electric lathes mean that the jade can be worked both much faster and more finely. A piece that would have taken over two years to complete before 1950 would now only require only about two months, and senior craftsman Master Yu Ting is able to produce work in recognisably traditional shapes that are almost eggshell thin.

Most of the new pieces are collected in China and so are not well known to the Western market, these would make exciting additions to the National Museum’s historic collection.

Header image: Dog of Fo ornament of pale creamy grey jade with golden brown markings, carved as a crouching animal: China, Qing dynasty, late 17th – early 18th century (A.1978.589).