Among the array of beautiful objects in the display case, one leapt out at me: an ancient Egyptian object so startling in its bold design and exquisite craftsmanship that it immediately took my breath away.

‘Treasure’ is a particularly overused word in the world of ancient Egyptian artefacts, often indiscriminately applied to undoubtedly very interesting, but not always exceptional, objects. Yet, here—here was an undeniable treasure: a highly decorative cylindrical box, assembled from delicate inlays and veneers of ebony and ivory, with gilding. The central motif is the ferocious protective god Bes surrounded by a rich array of royal symbolism, including cartouches containing the name of Pharaoh Amenhotep II.

It captivated me on my very first visit to the National Museum of Scotland, and when I had the honour to become curator of the museum’s Ancient Mediterranean collection, it was one of the first things I wrote about in the object story Box of Amenhotep II.

But that was just the beginning: now newly rediscovered fragments of the box are reshaping our understanding its story, which will features in our exhibition The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial.

The box held more mysteries than I could imagine. Its exact origin is uncertain. The first record of the box in the museum is when it was assembled from fragments repaired under the direction of museum director Joseph Anderson. The eminent Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie wrote an article about the box in 1895: ‘in a recent visit to Edinburgh, Dr Anderson was good enough to show me a portion of a casket which he had rescued in fragments from a box of miscellanea belonging to the Rhind Collection, and had carefully reunited’. This collection included other royal items from the same era, from a royal tomb at Thebes belonging to a group of princesses, including granddaughters of Amenhotep II. So, their tomb seems to be the most likely origin for the decorative box. It is in incredible condition for an item that is 3,400-years old, but it is actually incomplete. The missing portion left a gap at the back of the box after the fragments were assembled.

Little did I expect that the gap could ever be filled! Before sieving became a common technique in excavations, it was not unusual for small items to be missed during the digging. Nowadays, as archaeologists revisit sites, a surprising number of ‘lost’ fragments belonging to objects excavated 100 years ago or more are being discovered. I was astonished when the missing fragments were discovered and brought to my attention, but initially they raised new questions.

One fragment looks significantly different to the design on the box, but it clearly connects to the other fragment and that one matches the box exactly. So why didn’t it match? Historic photos and beautiful drawings of the box by the late Cyril Aldred, a former curator at the Museum and a foremost expert on ancient Egyptian art, revealed the answer: the band of decoration around the lower edge of the box had originally been severely damaged and subsequently restored in the 1950s – unfortunately incorrectly.

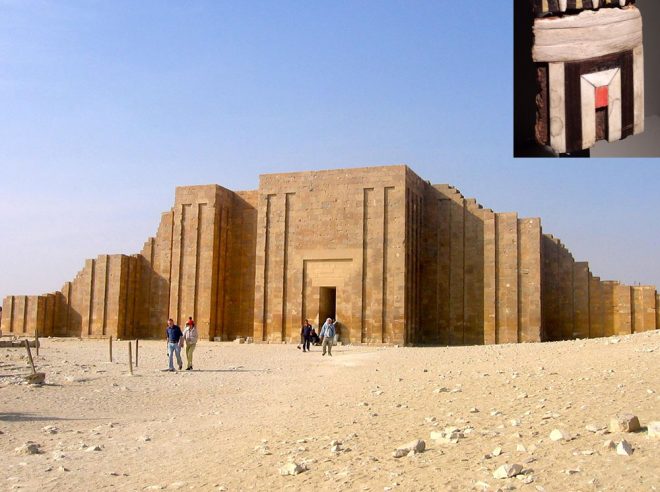

The only surviving elements on the box were a few vertical stripes of ebony and ivory. It is understandable that the restorer interpreted that this must have been an alternating pattern of vertical stripes, however, this kind of design is not represented anywhere else in Egyptian art. The closest comparable use is motif of vertical stripes flanking a central rectangular arch that evokes the façade of the royal palace. The design dates back to the very beginning of Egyptian history, though it continued for millennia afterwards. It is thought to represent the mud-brick and reed exterior of a royal palace; as such, it was closely bound with the concept of kingship. The palace-façade design on the rediscovered fragment has revealed important new information about the original design and rich symbolism of the Amenhotep II box, and a further clue about its origin.

The palace design running along the base, providing the foundation to the entire box. Indeed the palace could represent the king himself; the word ‘pharaoh’ comes from the Egyptian per aa, meaning ‘great house’ or ‘palace’. From this design, papyrus plants sprout, emblematic of Egypt itself. The oval-shaped ivory plaques depict cartouches containing the throne name of Amenhotep II on top of the hieroglyph for ‘gold’, which symbolised divinity and eternity. The symmetrical decoration on either side of each cartouche depicts notched palm ribs, which were used to record the length of a king’s reign time, depicted on top of circular shen-rings, the hieroglyph for eternity. This royal symbolism is combined with the god Bes, who was more usually associated with more humble domestic contexts as the protector of households, and especially women and children. Thus, the box demonstrates a more personal side to the world of the pharaoh.

The new fragments further strengthen the theory that the Amenhotep II box came from the tomb of his granddaughters and was used by the princesses in their daily life in the actual palace. Few palace objects survive from Egypt, so this royal box offers a rare insight into that exclusive world. It probably originally held cosmetics, although perfume or jewellery are also possible candidates. Its staggering to think of the amount of effort that went into creating such a small item that would have been used entirely in private. The Amenhotep II box is a masterpiece of ancient craftsmanship that ranks among the finest examples of decorative woodwork to survive from Egypt. The craftsmanship is most closely comparable to that of caskets discovered in the tombs of Tutankhamun and his grandparents. The complex yet harmonious design, the richness of the materials, and the exquisite carving makes it an object of significant artistic importance. Now the fragments are enhancing our understanding of this extraordinary artwork.

Happily, the fragments of the Amenhotep II box have now been acquired with the support of the Art Fund and the National Museums Scotland Charitable Trust. Soon visitors will be able to see them reunited with the box on display in the exhibition The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial, which focusses on the story of the tomb found next to that of the princesses.

Many thanks to Egyptologists Marcel Marée and Tom Hardwick and National Museums Scotland artefact conservator Charles Stable for their helpful discussions about the box and fragments.

The Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Burial presents the story of one extraordinary tomb, built around 1290BC and reused for over 1000 years. The exhibition opens on Friday 31 March until 3 September 2017 at National Museum of Scotland.