Now we’ve wiped the mud from our boots, put away our trowels and had a chance to think about the results – what did we find?

You may remember my last Torrs blog, which was written as we were about to go digging to examine the find-spot of the amazing Torrs pony cap, which was a star piece in our Celts exhibition.

The findspot of this Iron Age masterpiece lies close to Castle Douglas in Galloway, but the exact location isn’t clear. It was found in 1812, when recording was a wee bit less precise than today! We know it was discovered in peat, probably during drainage works, in an area which used to be a loch – but there are several candidates as this was once a very wet spot. We wanted to see if we could pin down where it came from and find out what was happening in the area at the time, during the third century BC. So we looked at a nearby Iron Age hillfort and explored the surrounding landscape by various scientific techniques.

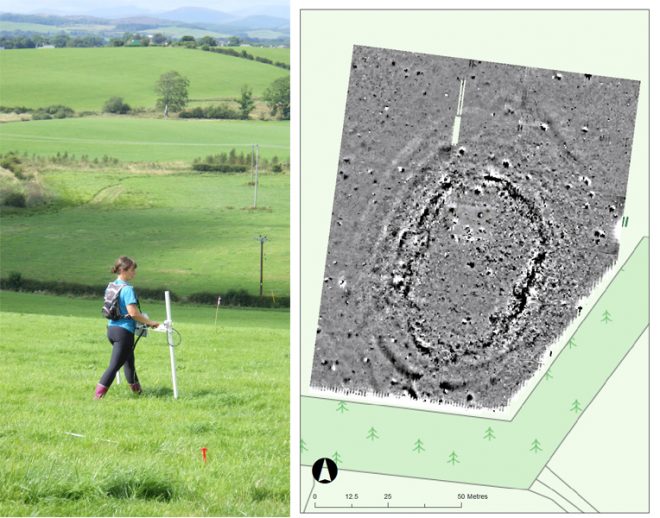

Let’s start with the hillfort. Today it survives as subtle mounds and hollows marking the plough-worn ramparts and ditches, though it takes a trained eye to see them. But we had help – the magic of geophysical survey, which lets you see beneath the soil. We used a technique called magnetometry, measuring variations in the earth’s magnetic signal caused by things such as cooking hearths and rubbish dumps. Thanks to our colleague Tessa Poller from Glasgow University, we were able to get a preview of what lay under the turf of the hillfort.

The results were fascinating. The hillfort jumps out at you, with two curving oval lines of the ditches and a messy black and white circuit marking the rampart. This was intriguing, as it suggested there was a lot of magnetically-rich stone in it. You can see a clear entrance at one end, and subtle traces of a later rectangular building reusing the rampart, but what’s really interesting is how quiet the interior is. There’s no hint of houses or hearths.

This whetted our appetite. We set about digging a big trench over the rampart system. There were two whopping great ditches, which tested our fitness as we dug out the thick, heavy clay layers in the base, and remains of a big rampart. This had a long history with at least three phases. The first rampart was a large dump of earth and clay with stone revetments. It was refurbished at least once, and then rebuilt in a different style. This last phase had two concentric timber palisades held fast in stone-lined slots (which formed the messy black and white line on the geophysics). The palisades would have been linked together into a hefty timber-framed structure known as a box rampart, which must have used an enormous amount of wood.

The interior was more of a challenge. We dug two big trenches, but found almost nothing – except a 19th-century trig point from the early Ordnance Survey mapping of the area!

We tried other techniques, working with local metal-detectorists to look for clues. They slaved long hours in unyielding terrain, producing a crop of horseshoes and tractor parts, but nothing of any great antiquity.

We also had local schools out to learn about their history, to see what archaeologists do – and to lend us a hand, (There’s a thin line between enthusiastic assistance and child labour, but I think we stayed on the right side of it …)

The results of this were interesting. The kids sieved the mixed-up ploughsoil which we’d taken off with a JCB. They found lots of modern material and some bits of flint and quartz from earlier prehistory, but nothing to suggest an Iron Age settlement – not even charcoal and burnt stone, which is the standard debris from a prehistoric site. Along with the lack of pits and postholes, it suggests this hillfort wasn’t a permanent settlement. More likely it was a central place for a community’s ceremonies and rituals, a place of safety and gatherings.

But the kids did reveal some lovely finds. The highlight was a broken flint knife, its edges beautifully shaped by careful chipping. This dates back about 4,000 years, to the Early Bronze Age.

So, we have an Iron Age fort which was used but not lived in. We don’t know what precise date it is yet – we’d no diagnostic finds, so we’ll need to rely on fragments of charcoal and charred seeds to get radiocarbon dates, if there is actually any charcoal in our samples! So keep your fingers crossed…

What about the wider landscape? Survey of the area by Michael Stratigos (Aberdeen University) and Richard Tipping (Stirling University) showed that the hillfort stood on what was virtually an island in prehistory, with bogs all around. The drainage schemes of the 18th and 19th centuries have totally changed the landscape here. But we can reconstruct it thanks to cores drilled into these former lochs and bogs. We showed that there are rich, well-preserved peat deposits which survived the 19th-century drainage, and these contain vital clues to the environment at the time. The next stage will be to seek funding to reconstruct the landscape and climate at the time the pony cap was buried in the third century BC.

We can also now be quite confident that the cap was found in Torrs Loch, as this fits all the clues from the early accounts. It was buried in the marshy fen edges of the loch, probably as an offering. But any other offerings remain hidden – the peat has only given up a few of its secrets so far…