Today I learned a new word: paraskevidekatriaphobia. Otherwise more commonly known as ‘Fear of Friday 13th’.

Indeed, the eagle-eyed among you might have already noticed that today is one of the unluckiest days of the year. This morning, I’ve managed to cross paths with my neighbour’s black cat and stepped boldly underneath a ladder on George IV Bridge. It would seem my luck is out. Which might be why I felt brave enough to delve into our collections in search of the unluckiest tales we have on display. Read on and make sure to cross your fingers…

Pilcher’s Hawk

This Victorian glider is set to soar once again when our six new Science and Technology galleries open next year, but the story of Pilcher’s Hawk is actually one of the most melancholy in our collections.

The Hawk was designed and built by Percy Pilcher, a British aviation pioneer. In 1897, he used it to break the world distance record, flying unpowered for 250 metres. Only two years later though, a tragic accident cut short his flying endeavours. During a demonstration in September 1899, Pilcher plummeted to the ground with the Hawk still on top of him. He died from his injuries on 2 October 1899.

This was only the start of the Hawk’s misfortune; the 20th century was not kind to the glider. Badly damaged, it was loaned to the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain for ten years, who displayed it as it was left on that fateful day in 1899. By 1909, the Hawk was on its way to Scotland. First under the care of the Royal Scottish Museum, it was restored and loaned to the Scottish Aeronautical Society for the 1911 Scottish National Exhibition in Glasgow. Then tragedy struck once more. In November 1911, the building housing the Hawk was wrecked during a storm, damaging the glider again.

Luckily the Royal Scottish Museum was able to restore the glider, displaying it until the outbreak of the Second World War. Now in our engineering conservation laboratory, our conservators are carefully looking after the delicate bamboo and fabric frame before it goes on display. Perhaps its luck is on the turn.

See it for yourself: In our new Science and Technology galleries, National Museum of Scotland, opening Summer 2016.

Gold, gold! Our kingdom for gold!

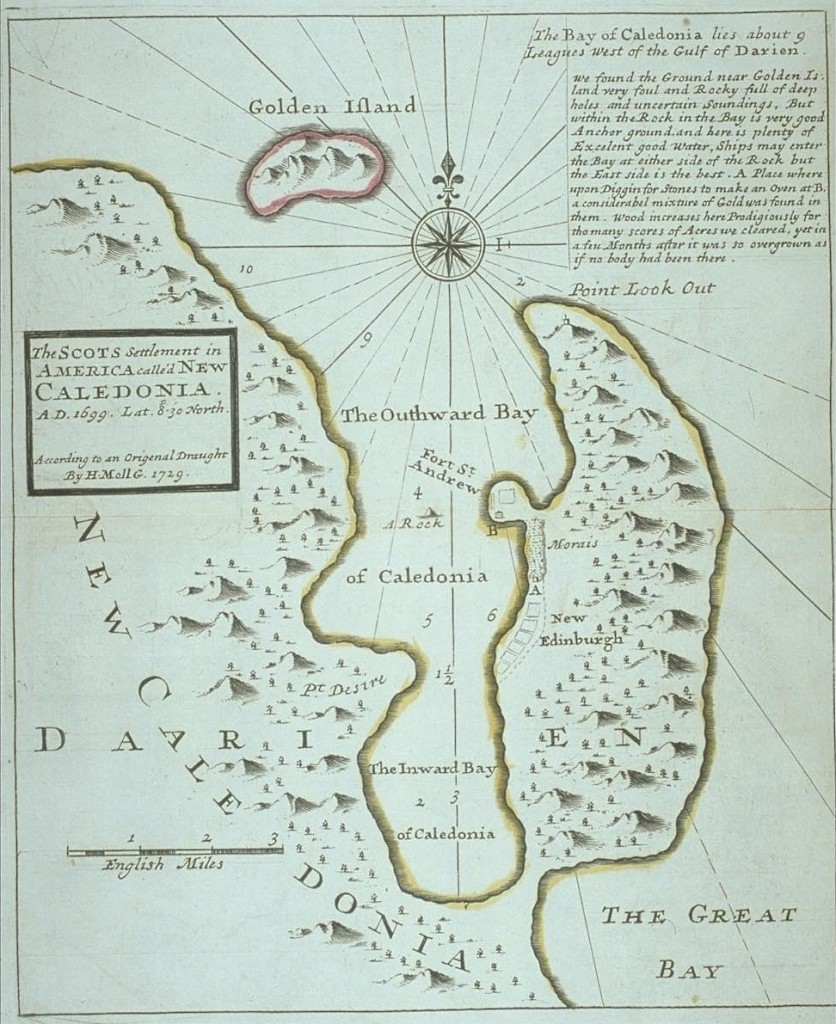

Our next unlucky object played a part in one of the darkest chapters in Scotland’s history: the Darien expedition. This treasure chest was used to store money and documents associated with the Company of Scotland, a trading company set up in 1695 with the power to establish colonies. It’s now remembered for the disastrous venture to establish a trading colony in the isthmus of Darien in 1698. This failure cost 2,000 lives and lost Scotland a quarter of its liquid capital. The loss of such a huge amount of capital helped to push Scotland towards an incorporating union with England.

The first expedition set sail from Leith on 14 July 1698, finally making landfall on 2 November 1698. The settlers constructed Fort St Andrew as the main defence and began to erect huts of the main settlement, New Edinburgh. Agriculture proved to be difficult and local tribes, although friendly, refused to buy combs and trinkets offered by the colonists. With the onset of summer, the stifling heat added to other causes and there were a great many deaths. In July 1699, barely eight months after arriving, the colony was abandoned. Only 300 of the 1,200 settlers survived and only one ship managed to return to Scotland.

But word of the disastrous first expedition didn’t reach Scotland in time to prevent a second voyage of more than 1,000 people. It arrived on 30 November 1699 to find the settlement of New Edinburgh deserted. Fear of being driven out by the Spaniards led them to attack the Spanish fort at Toubacanti in January 1700. The Scots were then subjected to sustained attacks at Fort St Andrew for a month before surrendering and leaving.

Of the 2,500 settlers that set off from Scotland in this ill-fated journey, just a few hundred survived.

See it for yourself: New Horizons, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland.

The Curse of Scotland

We all know that playing cards requires a cool head, an impassive poker face and more than a little bit of luck. Best hope then that the Nine of Diamonds doesn’t make it into your hand.

Since the early 18th century, players holding this particular card are said to be unlucky and working against The Curse of Scotland. There are various explanations why, with the card at various times symbolising royal tyrants from Scottish history, an exclamation by the Duke of Monmouth before the fateful Battle of Bothwell Bridge, and the Scots’ supposed hatred for the powerful “Pope” card in 19th-century card game Pope Joan. Amongst other things…

This pack of 53 playing cards was engraved in 1691 by Walter Scott, an Edinburgh goldsmith. The cards show the royal arms and the arms of Scottish nobility who sat in Parliament at the time.

See it for yourself: New Horizons, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland.

Hubble, bubble, toil and trouble

Belief in the existence of witches, magic and sorcery was widespread in early modern Europe, with large-scale hunts and trials held as the ‘witch craze’ spread across the continent. For the early modern victim of bad luck, it was very easy to place blame. A poor harvest, a sudden illness, an unrequited love – all could be attributed to the presence of witchcraft. But as some of these wicked gems from our collections show, perhaps their fears weren’t entirely unfounded.

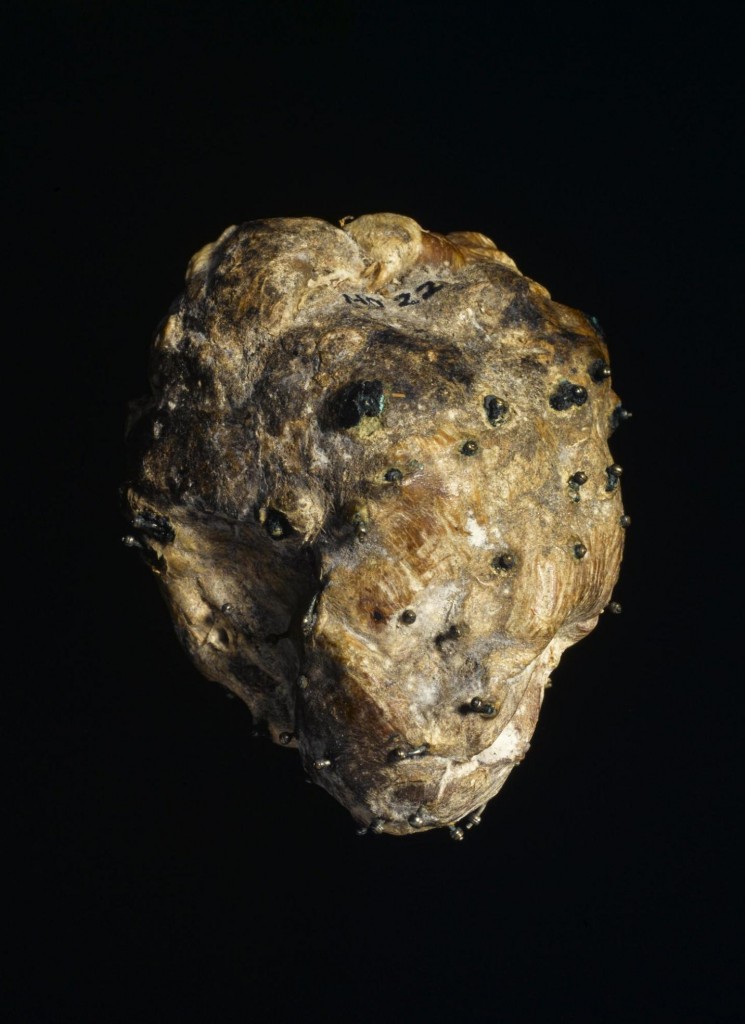

This calf’s heart was found in Dalkeith, Fife. Stuck full of pins, we think it was used as a charm in witchcraft.

As was this cursing bone, fixed through a diamond-shaped piece of bog wood. It belonged to a reputed witch in Glen Shira at Inveraray in Argyll who supposedly used it to ‘ill-will’ people in the community. According to a local tradition collected by Lady Elspeth Campbell, the blood of a newly-killed hen was poured through the bone as a curse was spoken.

It’s all too easy today to dismiss this steadfast belief in evil, but for the women and men who lived through the terror of a witch hunt, luck played no part in their trial.

This witch’s collar, known as ‘jougs’, was used to hold offenders by the neck and expose them in a public place for censure and ridicule. They were common in Scotland from the 16th to the 18th century; this iron example was owned by the parish of Ladybank in Fife during the 17th century. The collar has serrated edges and a ring for the attaching of a chain. The chain would usually be fastened to the kirk wall or gate, or to a post or tree.

See it for yourself: Daith Comes In, Level 4, National Museum of Scotland.

A fair Maiden

This object isn’t unlucky in itself, but those who came into contact with it most certainly were. Long before the French Revolution, the Scots had invented and were using this beheading machine known as the Maiden.

Between 1564 and 1710, when the Maiden was withdrawn from use, more than 150 people were executed with this ‘humane’ device. The condemned from all parts of Scotland were brought to Edinburgh to be executed. The records of the Justiciary Court of the time document various misdemeanours for which a person might suffer execution by the Maiden. These included murder, incest, stealing, treason, adultery, forgery and robbery.

Ironically, the person believed to have introduced the idea for a beheading machine to Scotland was himself executed by the Maiden. James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, ruled Scotland from 1572 to 1578 during the minority of James VI. He worked hard to maintain friendship with England, dealing ruthlessly with Mary, Queen of Scots‘ supporters. He was implicated in the murder of Mary’s second husband, Lord Darnley, and beheaded on 2 June 1581.

See it for yourself: Monarchy and Power, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland.