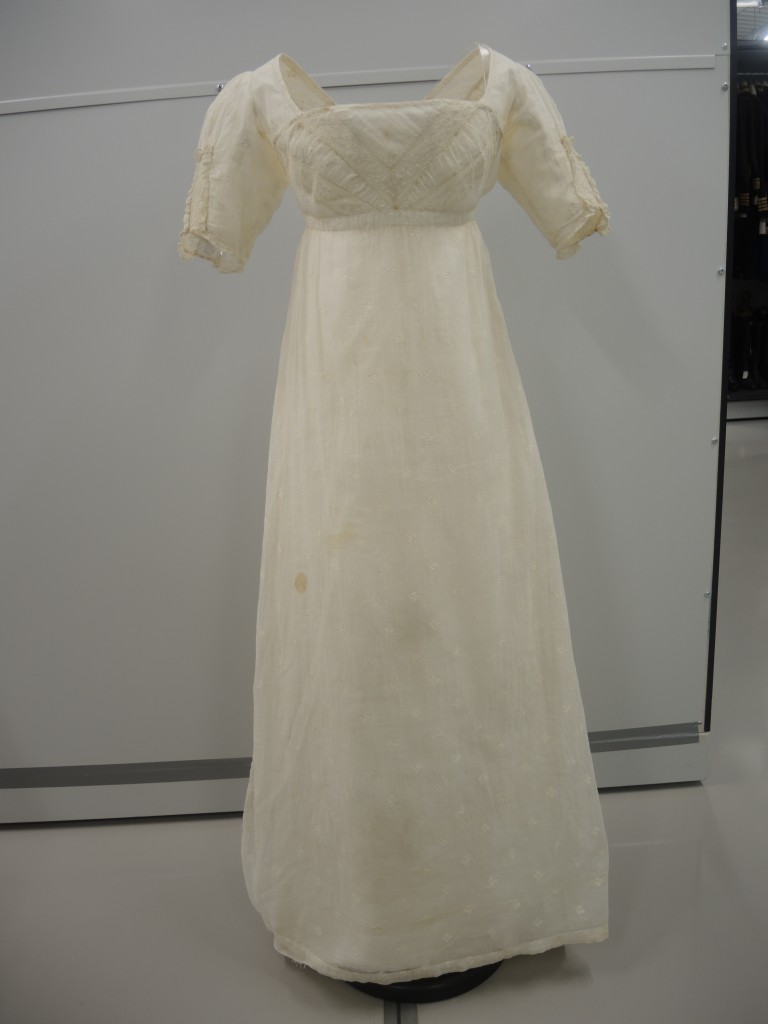

This dress of white muslin tambour is an example of an early 19th-century empire-waisted dress. It has a stomacher front, lace trimmings and is embroidered all over with little white flower sprigs. It is going in our new Fashion and Style gallery, opening next year. Textile conservator Miriam conserved the dress by washing it to remove some of the staining and then it was handed over to me for mounting.

We’re working with object mounting specialists Museum Workshop to create acrylic cutaway mannequins which will be completely transparent. The idea is that the costumes will be the main focus, without the distraction of mannequin heads and necks sticking out.

This dress worked particularly well with these mannequins because it is so light. When the mannequin was cutaway to the shape of the neckline, you could still see the seams and the light floaty muslin. This was especially important as the style of the early 19th century was to have very transparent dresses, to copy the sculptures of Ancient Greece and Rome.

However, a problem we faced was that because the dress was so light, it was possible to see where the mannequin stopped and started, especially at the bottom around the hip. It was my job to try to keep the soft lines whilst covering up what was happening underneath.

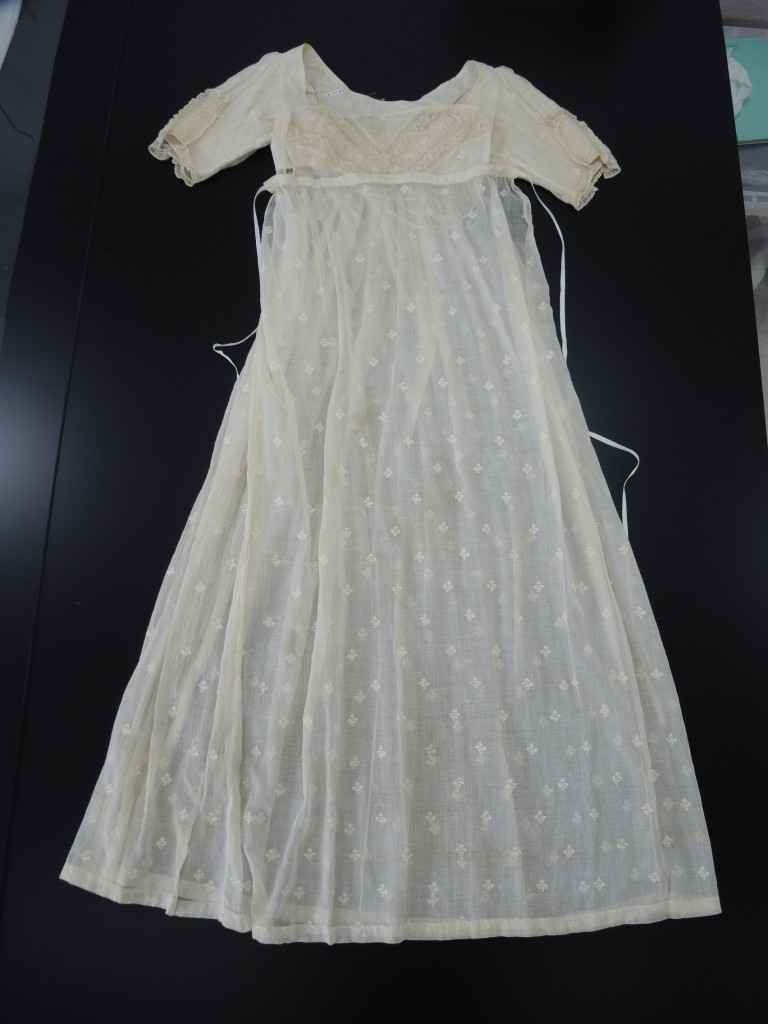

I did this by first creating a calico petticoat to go under the skirt. I stopped it at the waistline so that it was possible to still look into the mannequin and see the construction of the dress. The calico petticoat worked to cover up the bottom of the mannequin, although it was a lot stiffer than the floaty muslin. To keep the soft line, I then put another petticoat made of silk habotai over the top of the calico. I also gathered it at the back to give some support to the gathers in the skirt.

Since the petticoat had no bodice, I had to find a way to attach it at the waist. Acrylic is very slippy and it’s not possible to stitch directly into the mannequin, as you can with standard mannequins. This meant I had to drill holes through the torso to be able to sew into. I also drilled holes around the neckline so the dress won’t slip down when it’s on display.

The transparency of the dress also caused problems at the front bodice. Because the stomacher piece was made of lace, it was possible to see the cotton lining beneath it. Moreover the dress needed padding around the bust. Unlike the dresses of the 18th century, where the bust was very flat, during this period a much more natural look was sought which meant a much fuller, more rounded bust. Inspired by the success of the habotai as a soft petticoat, I created a little habotai padded bag to go between the cotton lining and the bodice front.

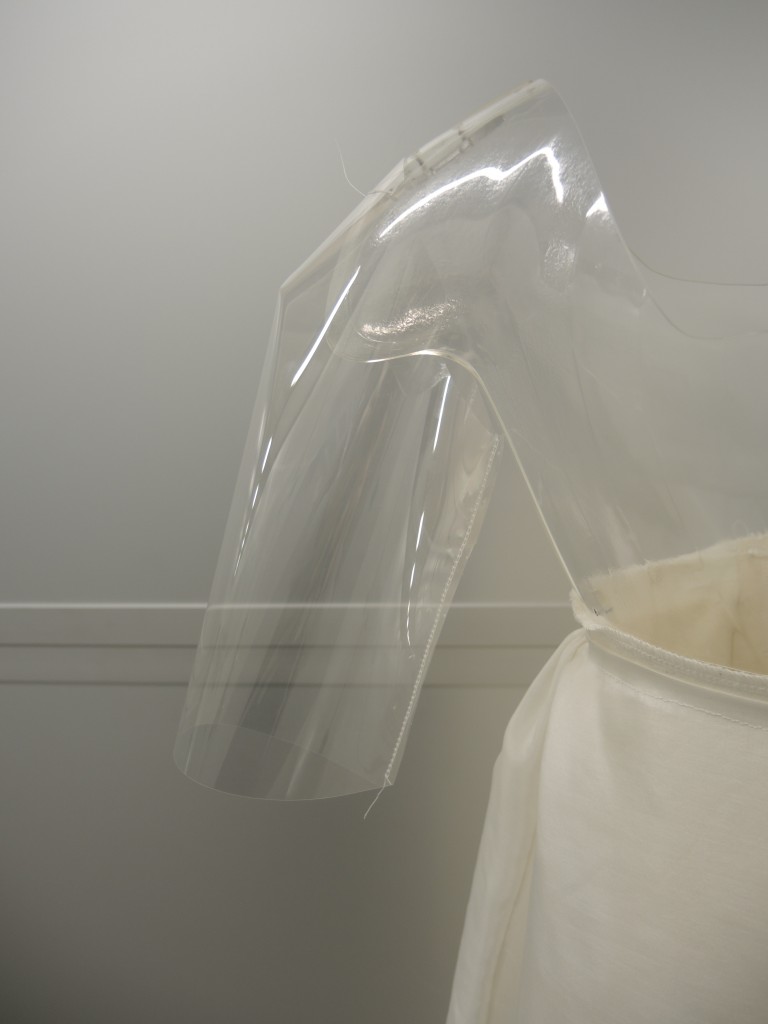

Finally, I made arms to fill out the sleeves. I wanted the arm support to look like a continuation of the mannequin as the transparency of the acrylic was so successful. I experimented with different weights of melinex, and with where to stop and start the support so the arms didn’t look too stiff or as though they were sticking out of the sides. In the end, I took a sleeve pattern and made a melinex arm that went under the sleeve and attached at the shoulder. By altering how much the melinex was overlapped at the shoulder seam, I could lower or heighten the sleeve.

This mounting project aimed to keep the softness of the dress and emulate the style of the time. However, I also had to keep in mind our in-gallery aim of making the dress itself the focus and the mannequin as invisible as possible. I hope the finished mannequin manages to do both – come and have a look for yourself in Summer 2016!