With the rise of smartphones and social media, photography is now often taken for granted. It began, though, as a pastime for wealthy Victorians, becoming more accessible throughout the 19th century as technological developments made it cheaper.

Curating the Photography: A Victorian Sensation exhibition has enabled me to showcase the early photographic collections of National Museums Scotland, including the Howarth-Loomes collection, much of which has never been publicly displayed.

The exhibition charts the evolution of the photographic image, and includes apparatus that illustrates changing 19th-century photographic techniques. The era is beyond living memory, yet the people in these early photographs are not so different to us. Here, I choose five images that speak clearly to me.

1. Girl holding the portrait of a man, Ross & Thomson of Edinburgh, 1840–1855

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the first form of photography shown to the early Victorians. The Parisian showman had already dazzled London audiences with his diorama, a show of lights and illusion. His photographs were one-off reversed positive images made of a delicate mercury amalgam resting on a polished silvered plate. Their mirror-like quality entranced the upper classes, who could not get enough of these reflections of reality. Since they were relatively expensive to produce, only those with enough disposable income could afford them. Even so, studios sprang up across the country and portraits inspired by the miniature paintings of the preceding age were taken of loved ones. This delightful portrait taken by the Edinburgh photographers Ross & Thomson shows a girl propped up on a striped cushion and holding a framed portrait, presumably of her dead father. James Ross and John Thomson were renowned for their portraits of children. While we don’t know who the sitter is, one of our visitors might.

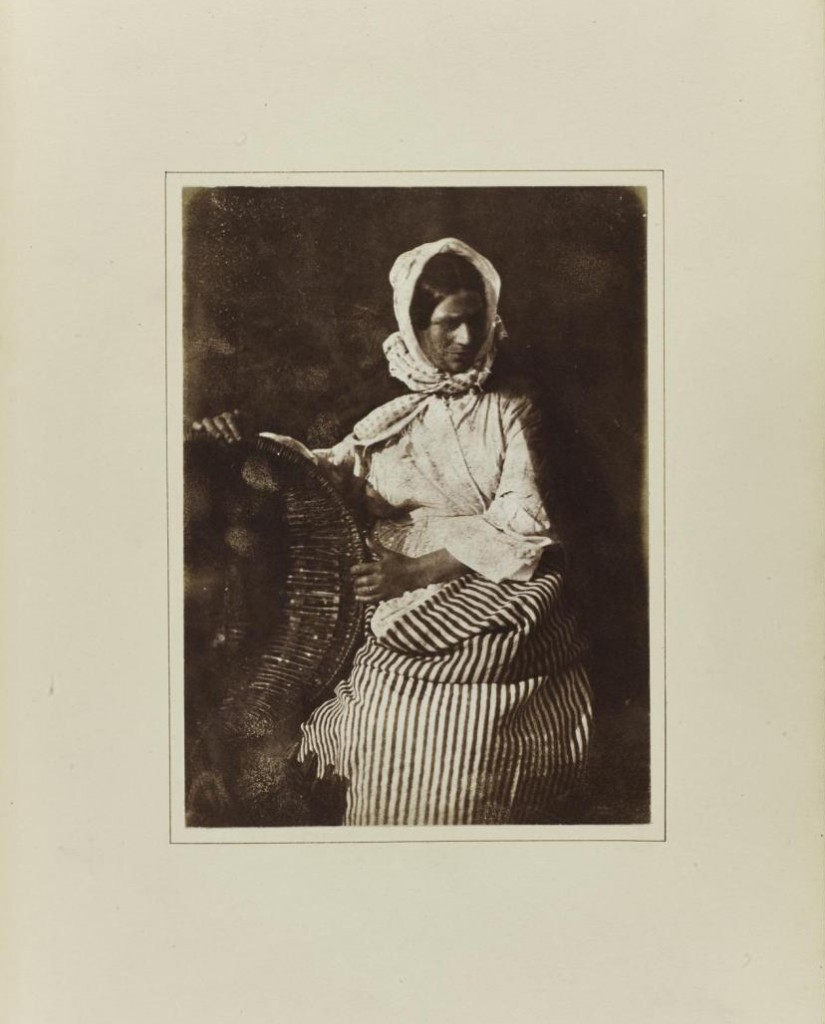

2. Mrs Elizabeth (Johnstone) Hall, D O Hill and Robert Adamson, 1840s

Robert Adamson helped pioneer W H F Talbot’s calotype process, working from his Edinburgh studio. The calotype produced a paper negative from which positive prints could be made. He and artist David Octavius Hill photographed dissenting ministers during the Disruption of the Church of Scotland in 1843, making artistic and technological advances together. Among their most beautiful work is this portrait of a Newhaven fishwife.

3. Horse and groom, London School of Photography, 1858–1860

The wet collodion process, introduced in 1851, combined the detail of the daguerreotype with the reproducibility of the calotype. A glass negative was used, along with cheaper chemicals, and the image was captured more quickly. By placing a piece of black paper behind the wet collodion negative, the photograph could emulate the more expensive, cased, daguerreotype. Outdoor photography of tricky subjects could now be taken, including this London horse.

4. Balmoral Castle, George Washington Wilson, 1863

Another popular form of photography used binocular cameras to make images. These were then viewed through a device called a stereoscope, resulting in a 3D effect. The greatest provider of stereoscopic views in Scotland was George Washington Wilson, whose Aberdeen-based business was given impetus after Prince Albert invited him to document the building of the new Balmoral Castle. Some of his commissions were made publicly available and he died a wealthy man.

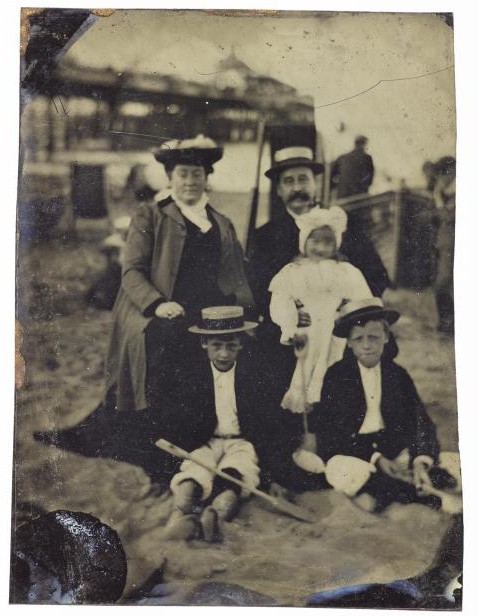

5. Family on the beach, Unknown, 1890

Ferrotype, or tin-type, photography was made cheaply with a wet collodion positive on tinned or enamelled iron. The process, introduced in 1853, produced poor-quality images that could nevertheless be handed to the customer minutes after being taken. Popular with itinerant photographers, this method of photography is particularly associated with the beach. Following the Bank Holidays Act 1871, working people had more opportunities to go on day trips and, with the spread of the 1871, working people had more opportunities to go on day trips and, with the spread of the railway network, often enjoyed family visits to the seaside. This image belongs to a group of tintypes showing the little boys growing older. We don’t know the family’s name, but a stencilled bucket in one photograph suggests they were holidaying in Margate.

Photography: A Victorian Sensation is showing at the National Museum Scotland until the 22 November 2015. #VictorianSensation