On 1 July 2015 scientists and marine biologists are celebrating International Polychaete Day. But what are polychaetes, and why are they so special that they deserve their own day?

What are polychaetes?

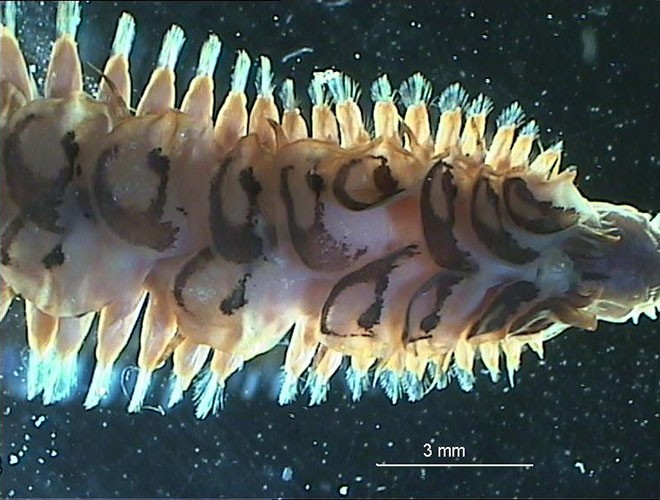

Polychaetes are marine bristle worms that belong to a group of animals known as annelids. All annelids have segmented bodies and obvious rings around the body. An annelid well known to most people is the earth worm, which has an obvious segmented body and constriction rings. It also has a few bristles along the body, which you can feel if you stroke the worm gently.

Polychaetes differ from earth worms as they have lots of bristles (polychaete means ‘lots of bristles’), are mostly marine and often display beautiful iridescent colours. They come in a wide variety of shapes and forms, from short and fat to long and thin, with fan-like tentacles, strange paddle-like structures, gills on each segment and big teeth-like feeding organs. They range in size from less than a millimetre to longer than a metre, although, the majority are 10 to 150mm so can be seen with the naked eye. A microscope will enable you to see the beautiful and diverse bristles and details of other characteristics such as tentacles, scales and gills.

Where do they live?

Polychaetes are common in the sand and mud of the sea bed and, like earthworms, they burrow. Unlike earthworms they also make tubes of limestone (calcium carbonate), mud or pieces of shell, sand and bits of debris. Sometimes the tube building can lead to massive reefs in both temperate and tropical environments.

Not all polychaetes build tubes however, and many live amongst seaweed or under rocks and boulders. They can also burrow into rocks and the shells of other animals. You can find polychaetes on the shore and down to thousands of metres in the world’s deep trenches, from polar to tropical seas, and even the hot vents of the deep ocean. More strangely, there are other polychaetes that live their entire lives in the open ocean and never touch the sea bed or any rock faces.

Why are polychaetes important?

If you take a shovel of sand and mud from the shore or sea bed and sieve it with a fine mesh sieve (0.5mm) the majority of animals you find will be polychaetes. They are burrowing and turning over the sediments of the sea bed to various depths and feeding on organic matter. They also provide a source of protein for many other animals, such as crabs and fish. Some polychaetes are collected or cultured commercially as bait for anglers, such as the king ragworm Alitta virens.

How many are there in the world?

There are estimated to be around 10,000 species of polychaetes in the world but there are many undescribed species so this is probably an underestimate. There are around 1,000 species at present in British waters and even here, where the living world is relatively well known, new species are being discovered every year.

Why do I like polychaetes?

Polychaetes are beautiful when they are alive and there are not many jobs in the world where you can enjoy looking at beautiful things. There are also many different kinds so I am never bored trying to find out what is living around our seas. There is always something new to learn about where they live or how they are related to each other.

Not many people look at polychaetes as they are soft bodied and do not look interesting when they are preserved in alcohol. They were first described to me as looking like chewed bits of string! You need to be patient, however, and if you use a microscope the wonderful shapes of the bristles are revealed. Most literature about polychaetes dates from the 1850s to the present day but it is not easy, as it is in many languages. Fortunately, some of the older books have hand-coloured plates of living specimens which are very life-like. If you have the opportunity to look at living specimens they are inspiring and there is so much to discover that you are never short of questions.

National Museums Scotland has a large collection of polychaetes acquired over many years by members of staff and government agencies and environmental consultancies. The collection is a useful resource to help identify unknown specimens, as a taxonomic research tool and to examine community structure.

What is International Polychaete Day?

To celebrate the beauty and diversity of polychaetes, 1 July 2015 has been named International Polychaete Day, in honour of the Zoologist Kristian Fauchald, who inspired many people to look at polychaetes by his enthusiasm and kindness.

#InternationalPolychaeteDay

This Storify post from @CardiffCurator pulls together all the action from International Polychaete Day.